Comprehensive, country-specific understanding of housing and mortgage markets can help calibrate monetary policy

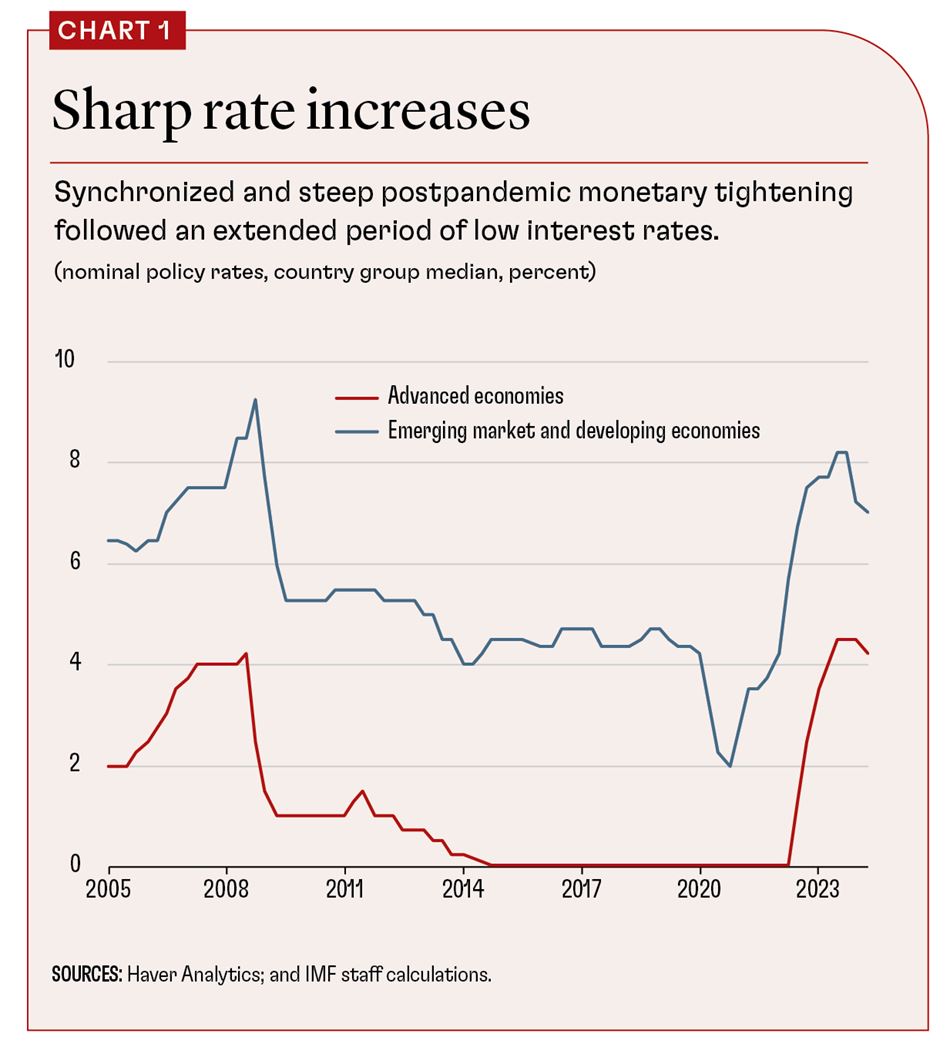

Central banks in late 2021 kicked off the steepest and most coordinated series of interest rate hikes in four decades to contain the postpandemic inflation outbreak (see Chart 1). Many economists expected a sharp global slowdown, but many economies have instead held up relatively well, with only some seeing significant decelerations.

Why did some countries feel the pinch from higher rates and not others? Explaining this is especially timely as many central banks are now cutting rates. Housing and mortgage characteristics, which vary widely across countries and have changed in recent years, are one key reason, our research in a chapter of the IMF’s April 2024 World Economic Outlook

Housing has been an important driver of economic shocks, largely due to its central role in private sector balance sheets. Mortgages are often the largest liability for households and housing their most significant form of wealth. Real estate also accounts for a large share of consumption, investment, employment, and consumer prices in most economies. Banks and financial intermediaries are also often heavily exposed to the housing sector, making it a key component of monetary policy transmission.

Housing channel

Since the global financial crisis, economists have made significant progress explaining how monetary policy operates through housing markets, specifically in identifying the transmission channels that operate through housing and mortgage markets. We summarize a few of these channels below, by focusing on those related to household demand.

First, policy rate changes directly affect monthly mortgage payments for homeowners with adjustable-rate mortgages. Payments also rise when policy rates do, depressing disposable income and sometimes consumption, through what is commonly referred to as the “cash flow channel,” according to research by Marco Di Maggio and others.

Second, home prices are very sensitive to changes in interest rates, through evolving discount rates and via expectations about future returns. This expectations channel, also referred to as the risk premium channel, can impact how much buyers are willing to borrow and for how long, which in turn affects housing prices and credit conditions.

Third, when property prices fluctuate in response to changing policy rates, wealth effects can affect consumption by homeowners. In addition, owners in many countries can use their homes as collateral to borrow and finance consumption. When real estate prices fluctuate, so does the volume of collateralized credit, and consumption follows, as work by Atif Mian and Amir Sufi shows.

Transmission potency

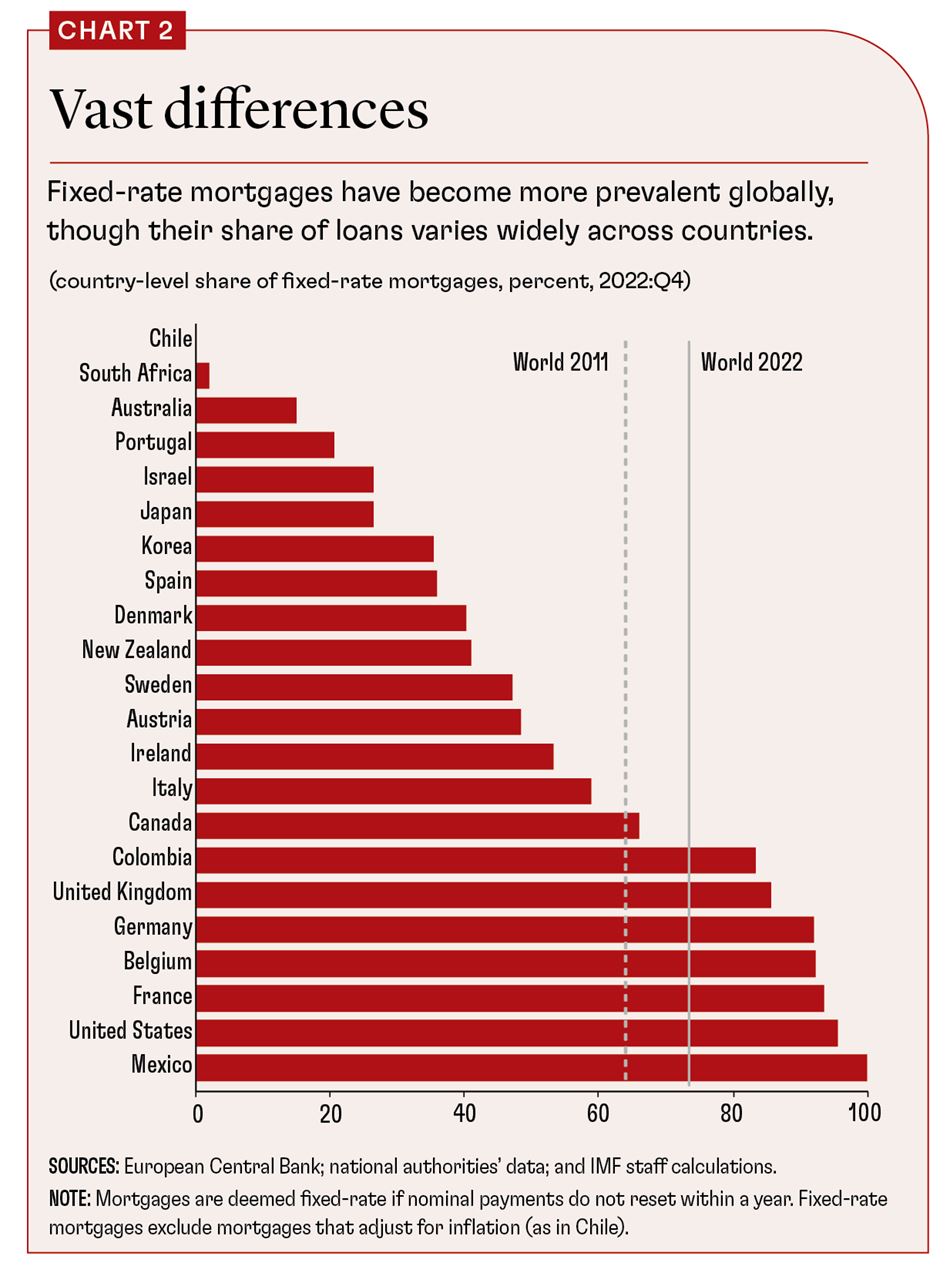

These transmission channels depend on key housing and mortgage market characteristics. For example, the relative strength of the cash-flow channel is determined by the share of fixed-rate mortgages—which, by definition, do not adjust to changes in policy rates—out of all outstanding mortgages. More fixed-rate loans mean fewer borrowers feel the pinch of rising policy rates, or benefit from their decline.

Our research shows that some key characteristics vary widely across countries. For example, the share of fixed-rate mortgages outstanding can vary from close to zero in South Africa to more than 95 percent in Mexico and the United States (Chart 2).

Could such differences explain why the degree of monetary policy transmission differs across countries? We find that policy has greater effects on economic activity in countries where the share of fixed-rate mortgages is low. In countries with a large share of fixed-rate mortgages, changes in policy rates will affect monthly payments for fewer households, and aggregate consumption will tend to be less affected.

Similarly, we see stronger monetary policy effects in countries where more households have debt and higher amounts of borrowing, as many more households will be exposed to changes in mortgage rates.

Housing market characteristics also matter: monetary policy transmission is stronger when housing supply is more restricted. For example, lower rates imply lower borrowing costs for buyers and increase demand. Slimmer supplies boost prices. Existing owners become wealthier and consume more, including by borrowing against homes.

The same holds true where home prices have been overvalued. Sharp price increases are often driven by overly optimistic views about appreciation. These are typically accompanied by excessive borrowing that, when interest rates rise, can lead to foreclosures and falling prices, and in turn lower incomes and less consumption.

Weaker transmission

Moreover, housing and mortgage markets have changed since the global financial crisis and the pandemic. At the beginning of the postpandemic hiking cycle, effective mortgage rates in many countries had fallen to multidecade lows, as households took advantage of low interest rates to secure low-cost loans in the 2010s and early 2020s. In addition, the average maturity of mortgages increased during that time, as the share of fixed-rate mortgages increased in many countries.

Meanwhile, many financial supervisors tightened macroprudential policies for housing financing after the global financial crisis. These policies aimed at limiting the risky lending that fueled boom-bust cycles in many countries during the mid-2000s. This paid off by 2020, with improved creditworthiness and reduced leverage. Separately, the pandemic prompted people to shift away from city centers and to areas with more supply.

Our research indicates that these shifts helped weaken or at least delay some monetary policy transmission channels in several countries. Transmission strengthened in some economies, such as those with fewer fixed-rate mortgages, higher debt levels, and constrained housing supply. But it weakened in others, where those factors moved in the opposite direction.

Our findings suggest that a deep, country-specific understanding of housing and mortgage markets is important to help calibrate monetary policy. In countries where transmission through housing channels is strong, monitoring housing market developments and changes in household debt-servicing ratios can help identify early signs of overtightening. Where monetary policy transmission is weaker, more forceful early action can be taken when signs of inflationary or deflationary pressures first emerge.

Loosening cycles

With many central banks now easing as inflation recedes, it’s natural to ask how housing and mortgage market characteristics will affect transmission in a loosening cycle. The housing channels we describe are active in both tightening and loosening phases, hence transmission depends on country-specific housing and mortgage market characteristics when policy moves in the other direction as well. Similarly to what happened during the postpandemic tightening cycle, we can expect a global easing cycle to affect each economy differently—and with important asymmetries.

History shows that tightening episodes are generally more powerful in restraining booms than similar size loosening episodes are in stimulating demand, according to research by Silvana Tenreyro and Gregory Thwaites. Yet most recent large and coordinated loosening cycles were followed by global recessions. During these periods, weakened private sector balance sheets prolonged economic slumps despite monetary easing, according to Atif Mian, Kamalesh Rao, and Amir Sufi.

The current easing cycle comes as household finances in advanced economies are stronger than during the years after the global financial crisis, and sometimes even relative to the prepandemic period. Similarly, there hasn’t been a significant increase in household default rates. The preexisting conditions of this loosening cycle differ substantially from historical experience, so its effects may also be different from usual.

Another key difference is the historically high share of fixed-rate mortgages as a proportion of outstanding debt. Typically, a high share of fixed-rate mortgages dampens the transmission of monetary policy during a tightening cycle, as homeowners with such loans are insulated from rising rates. In a loosening cycle, fixed-rate mortgages impair transmission less, as households with such loans may want to refinance at even lower rates, activating what is known as the refinancing channel of monetary policy, Martin Eichenbaum, Sergio Rebelo, and Arlene Wong show.

This time could be different, however. Many borrowers in advanced economies locked in historically low fixed rates during the 2010s and the pandemic. These mortgages may remain well below current rates despite monetary easing, leaving many households with little incentive to refinance.

In the United States, for example, the average rate for all outstanding mortgages was 3.9 percent as of late 2024, government data show, well below the 6.7 percent average for new 30-year fixed loans. This means that mortgage rates would have to decline about 3 percentage points for the average borrower with a fixed-rate loan to have an incentive to refinance. Homeowners with fixed rates are therefore likely to remain locked in despite lower borrowing costs, with important consequences on both spending and house prices.

Of course, monetary policy operates through many channels other than housing markets. Ultimately, the degree of transmission of any easing cycle to the real economy depends on many factors: the relative speed and strength of the loosening impulse; the pass-through of monetary policy to lending rates; the government’s fiscal stance; and supply-side factors, such as the cost of materials, many of which are beyond the direct influence of central banks.

Yet our results highlight that housing and mortgage markets are a key component of the transmission mechanism. Central banks should therefore closely monitor housing markets to best calibrate policy.

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect IMF policy.

References:

Di Maggio, Marco, Amir Kermani, Benjamin J. Keys, Tomasz Piskorski, Rodney Ramcharan, Amit Seru, and Vincent Yao. 2017. “Interest Rate Pass-Through: Mortgage Rates, Household Consumption, and Voluntary Deleveraging.” American Economic Review 107 (11): 3550–88.

Eichenbaum, Martin, Sergio Rebelo, and Arlene Wong. 2022. “State-Dependent Effects of Monetary Policy: The Refinancing Channel.” American Economic Review 112 (3): 721–61.

Mian, Atif, and Amir Sufi. 2011. “House Prices, Home Equity-Based Borrowing, and the US Household Leverage Crisis.” American Economic Review 101 (5): 2132–56.

Mian, Atif, Kamalesh Rao, and Amir Sufi. 2013. “Household Balance Sheets, Consumption, and the Economic Slump.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 128 (4): 1687–726.

Tenreyro, Silvana, and Gregory Thwaites. 2016. “Pushing on a String: US Monetary Policy Is Less Powerful in Recessions.” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 8 (4): 43–74.