This crisis unfolds even as the global economy has not yet fully recovered from the pandemic. Even before the war, inflation in many countries had been rising due to supply-demand imbalances and policy support during the pandemic, prompting a tightening of monetary policy. The latest lockdowns in China could cause new bottlenecks in global supply chains.

In this context, beyond its immediate and tragic humanitarian impact, the war will slow economic growth and increase inflation. Overall economic risks have risen sharply, and policy tradeoffs have become even more challenging.

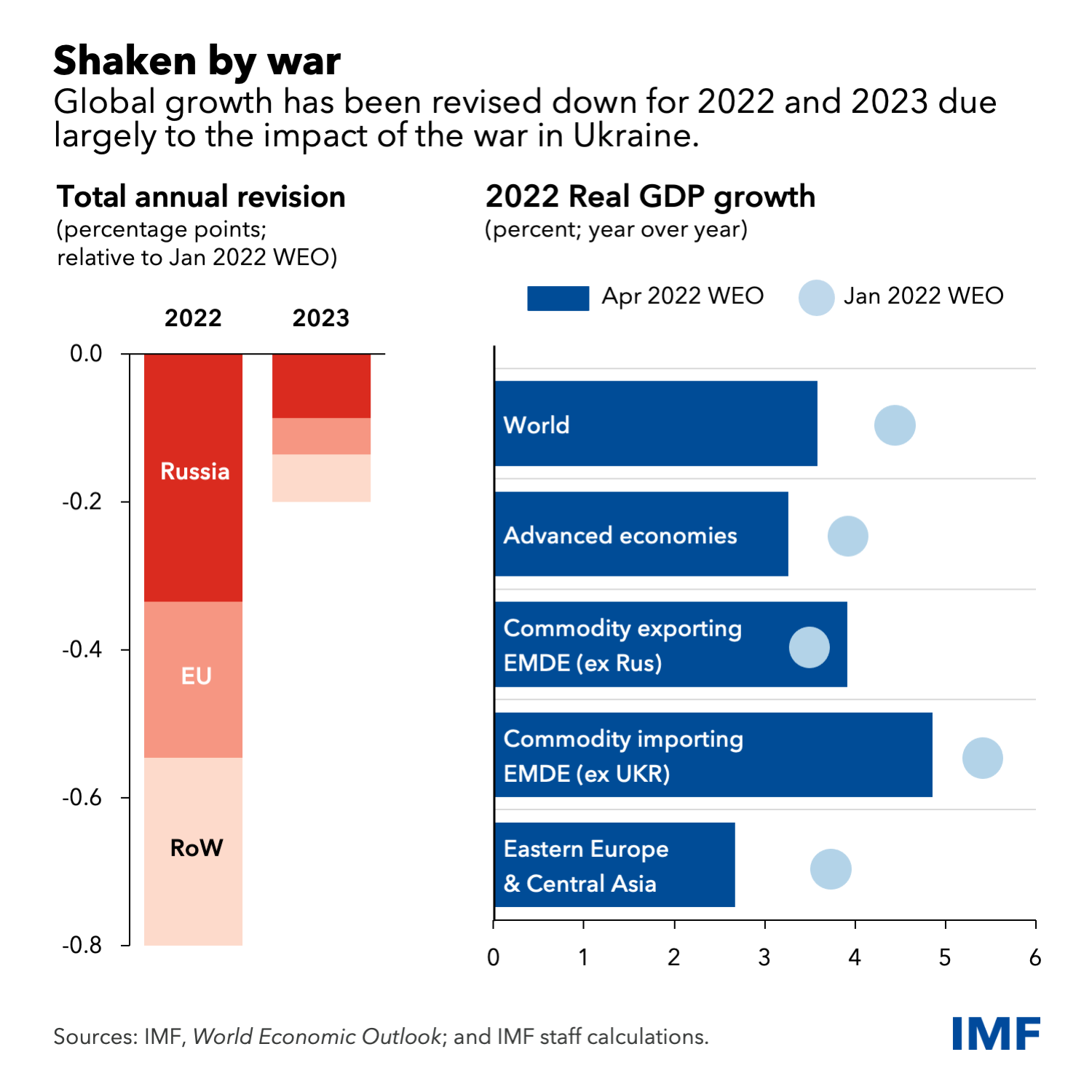

Compared to our January forecast, we have revised our projection for global growth downwards to 3.6 percent in both 2022 and 2023. This reflects the direct impact of the war on Ukraine and sanctions on Russia, with both countries projected to experience steep contractions. This year’s growth outlook for the European Union has been revised downward by 1.1 percentage points due to the indirect effects of the war, making it the second largest contributor to the overall downward revision.

The war adds to the series of supply shocks that have struck the global economy in recent years. Like seismic waves, its effects will propagate far and wide—through commodity markets, trade, and financial linkages. Russia is a major supplier of oil, gas, and metals, and, together with Ukraine, of wheat and corn. Reduced supplies of these commodities have driven their prices up sharply. Commodity importers in Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia, the Middle East and North Africa, and sub-Saharan Africa are most affected. But the surge in food and fuel prices will hurt lower-income households globally, including in the Americas and the rest of Asia.

Eastern Europe and Central Asia have large direct trade and remittance links with Russia and are expected to suffer. The displacement of about 5 million Ukrainian people to neighboring countries, especially Poland, Romania, Moldova and Hungary, adds to economic pressures in the region.

Pressures amplified

The medium-term outlook is revised downwards for all groups, except commodity exporters who benefit from the surge in energy and food prices. Aggregate output for advanced economies will take longer to recover to its pre-pandemic trend. And the divergence that opened up in 2021 between advanced and emerging market and developing economies is expected to persist, suggesting some permanent scarring from the pandemic.

Inflation has become a clear and present danger for many countries. Even prior to the war, it surged on the back of soaring commodity prices and supply-demand imbalances. Many central banks, such as the Federal Reserve, had already moved toward tightening monetary policy. War-related disruptions amplify those pressures. We now project inflation will remain elevated for much longer. In the United States and some European countries, it has reached its highest level in more than 40 years, in the context of tight labor markets.

The risk is rising that inflation expectations drift away from central bank inflation targets, prompting a more aggressive tightening response from policymakers. Furthermore, increases in food and fuel prices may also significantly increase the prospect of social unrest in poorer countries.

Immediately after the invasion, financial conditions tightened for emerging markets and developing countries. So far, this repricing has been mostly orderly. Yet, several financial fragility risks remain, raising the prospect of a sharp tightening of global financial conditions as well as capital outflows.

On the fiscal side, policy space was already eroded in many countries by the pandemic. Withdrawal of extraordinary fiscal support was projected to continue. The surge in commodity prices and the increase in global interest rates will further reduce fiscal space, especially for oil- and food-importing emerging markets and developing economies.

The war also increases the risk of a more permanent fragmentation of the world economy into geopolitical blocks with distinct technology standards, cross-border payment systems, and reserve currencies. Such a tectonic shift would cause long-run efficiency losses, increase volatility and represent a major challenge to the rules-based framework that has governed international and economic relations for the last 75 years.

Policy priorities

Uncertainty around these projections is considerable, well-beyond the usual range. Growth could slow down further while inflation could exceed our projections if, for instance, sanctions extend to Russian energy exports. Continued spread of the virus could give rise to more lethal variants that escape vaccines, prompting new lockdowns and production disruptions.

In this difficult environment, national-level policies and multilateral efforts will play an important role. Central banks will need to adjust their policies decisively to ensure that medium- and long-term inflation expectations remain anchored. Clear communication and forward guidance on the outlook for monetary policy will be essential to minimize the risk of disruptive adjustments.

Several economies will need to consolidate their fiscal balances. This should not impede governments from providing well-targeted support for vulnerable populations, especially in light of high energy and food prices. Embedding such efforts in a medium-term framework with a clear, credible path for stabilizing public debt can help create room to deliver the needed support.

Even as policymakers focus on cushioning the impact of the war and the pandemic, other goals will require their attention.

The most immediate priority is to end the war.

On climate, we must close the gap between stated ambitions and policy actions. An international carbon price floor differentiated by country income levels would provide a way to coordinate national efforts aimed at reducing the risks of catastrophic climate events. Equally important is the need to secure equitable worldwide access to the full complement of COVID-19 tools to contain the virus, and to address other global health priorities. Multilateral cooperation remains essential to advance these goals.

Policymakers should also ensure that the global financial safety net operates effectively. For some countries, this means securing adequate liquidity support to tide over short-term refinancing difficulties. But for others, comprehensive sovereign debt restructuring will be required. The Group of Twenty’s Common Framework for Debt Treatments offers guidance for such restructuring but has yet to deliver. The absence of an effective and expeditious framework is a fault line in the global financial system.

Particular attention should also be paid to the overall stability of the global economic order to make sure that the multilateral framework that has lifted hundreds of millions out of poverty is not dismantled.

These risks and policies interact in complex ways over varying timeframes. Rising interest rates and the need to protect vulnerable populations against high food and energy prices make it more difficult to maintain fiscal sustainability. In turn, the erosion of fiscal space makes it harder to invest in the climate transition, while delays in dealing with the climate crisis make economies more vulnerable to commodity price shocks, which feeds into inflation and economic instability. Geopolitical fragmentation worsens all these trade-offs, increasing the risk of conflict and economic volatility and decreasing overall efficiency.

In the matter of a few weeks, the world has yet again experienced a major shock. Just as a durable recovery from the pandemic was in sight, war broke out, potentially erasing recent gains. The many challenges we face call for commensurate and concerted policy actions at the national and multilateral levels to prevent even worse outcomes and improve economic prospects for all.