International initiatives must complement, not duplicate, national health strategies

Failure to learn from the response to COVID-19 could have grave consequences for global health. The pandemic exposed significant holes in the current international framework, including lack of coordination among multiple organizations and unequal vaccine distribution between high- and low-income countries.

Global health authorities now risk repeating past mistakes in response to the mpox outbreak in sub-Saharan Africa. This crisis underscores the familiar challenge of fragmented donor coordination, leading to slow and insufficient increases in funding. Countries on the front line of the outbreak still lack the systems and financial resources to effectively manage spread of the disease.

Low- and middle-income countries urgently need additional health resources. But existing resources must be spent efficiently, and coordination between international donors, public and private, should be improved. Developing economies do not allocate sufficient domestic resources to health, and a cumbersome donor architecture undermines external financing. A multipronged approach that prioritizes strengthening country health systems and integrates global initiatives into national strategies could have a lasting impact on health outcomes in these countries.

Daunting diagnosis

There is no single reason for the poor state of health systems in so many developing economies. It reflects a combination of weak public finances, insufficient external assistance, and poor coordination between national governments and international donors.

Small and unspent budgets: Public spending on health in low- and middle-income countries has stagnated at below 2 percent of GDP recently, about half what these countries spend on education—perhaps reflecting finance ministers’ perception that donors are doing enough. Spending increased during COVID-19, but many countries have since cut it back to prepandemic levels, preliminary data suggest.

This is particularly concerning given the growing demand for health services and the increasing burden of noncommunicable diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, and diabetes, which are rising because of aging populations, more environmental pollution, and changing lifestyles associated with higher incomes.

And money allocated to health budgets is often not fully spent, especially in sub-Saharan Africa. Underspending in the health sector is estimated to lead to a loss of $4 per person, based on constant 2020 prices. That loss equals what low-income sub-Saharan African countries spend on primary health care per person.

Low revenue, high debt: Tax collection in low- and middle-income countries has flatlined and deprived health and other social sectors of resources. In some low-income countries, tax revenue is less than 10 percent of GDP, significantly below the 15 percent recommended by the IMF.

Meanwhile, some developing economies spend over a third of the tax revenue they do collect servicing domestic and foreign debt, further constraining spending on education and health. The benefits of earlier debt relief initiatives, such as the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries Initiative of the mid-1990s and the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative of 2005, have eroded as countries became indebted again.

Stagnant donor assistance: Health aid remained stuck at about 1 percent of low- and middle-income countries’ GDP for the two decades or so before the pandemic, with only a small increase afterward. The outlook for future aid appears bleak given fiscal pressure on donor countries and shifting geopolitical dynamics.

As donor countries prioritize reducing their own high debt and spend more on defense and care for aging populations, a significant increase in health aid to low- and middle-income countries seems unlikely.

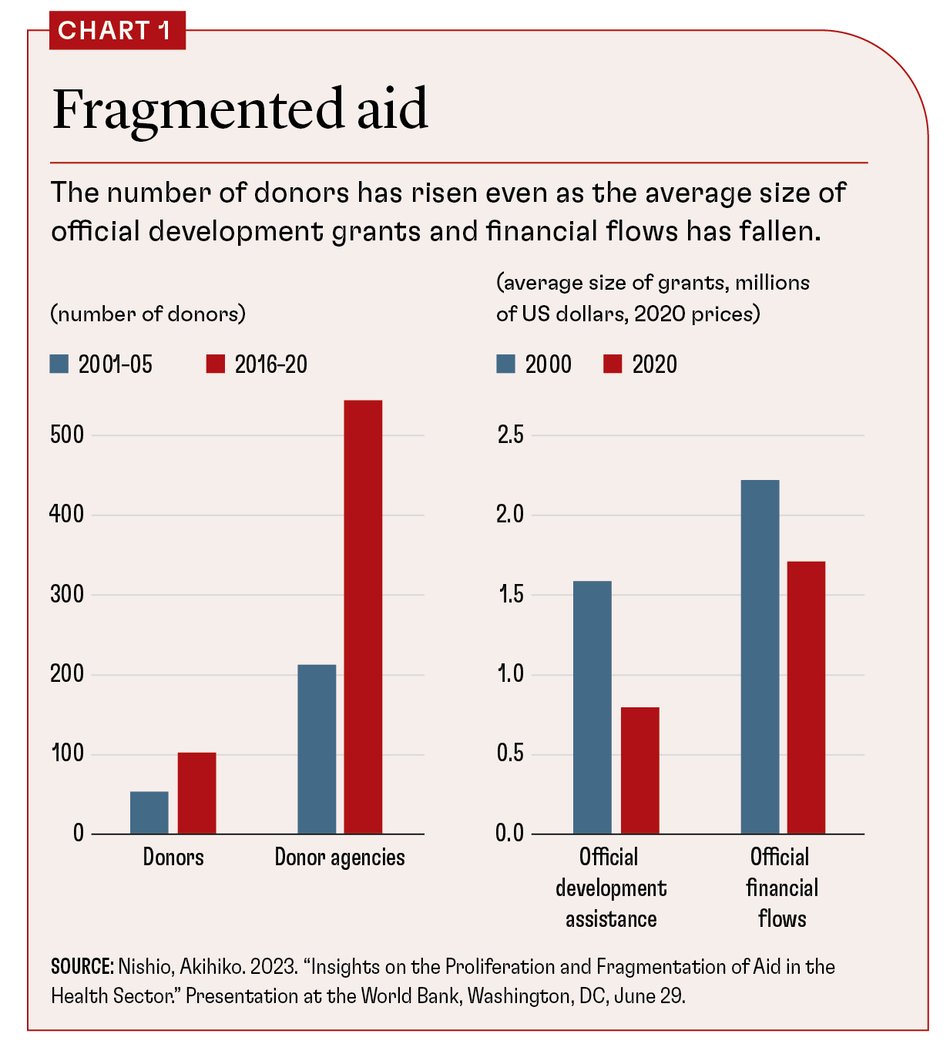

Fragmentation: External health aid is often volatile and prioritizes global agendas over national needs. Disease-specific programs, known as “vertical funds,” have proliferated and have led to a fragmented landscape of multiple donors operating independently, duplicating efforts, and breeding inefficiency.

Over the past 15 years, the number of donors of all types of aid has doubled, and the number of donor agencies has tripled. Yet donor financial flows have grown only by 50 percent, and the size of both official grants and official flows has decreased (see Chart 1).

The requirements donors impose on aid-receiving countries to ensure that funds are spent properly, driven by concerns about governance, are well-intentioned but cumbersome. They increase the cost of absorbing external resources and make it more expensive for countries to develop their own government capacities in health agencies.

Aid “localization”:Many bilateral donors channel aid through nongovernment agencies on the ground rather than directly through the receiving country’s health authorities. Recent initiatives, including by the US Agency for International Development, have increased local nongovernment participation in health aid, a process known as “localization”.

Continuing off-budget grant financing through local NGOs may prolong dependence on foreign aid and lead to perverse incentives for increasing domestic financing. It can also draw essential health workers away from local health ministries and create coordination challenges between country authorities and other donors.

Integrated approach

Treating this complex diagnosis requires a shift from single-focus interventions, aimed at controlling a specific disease, toward integrated approaches that consider the complex interplay between health, economic, and social factors. There is no need for a revolutionary approach: the 2023 Lusaka Agenda called for greater alignment of global health initiatives with country health systems and primary health care in Africa, consistent with the 2005 Paris Declaration on aid effectiveness.

To advance this agenda, the global health community would do well to recognize the need for reform and commit to an approach that strengthens countries’ health systems and integrates global initiatives with national strategies. After all, no country, regardless of income level, has achieved universal health coverage without major increases in public spending.

On the domestic side, countries must rely progressively more on their own resources, which are more stable. The goal should be to finance all or most core health activities domestically. For that, low- and middle-income countries need to increase revenues. These countries could raise an additional 5–9 percent of GDP over time, according to IMF estimates.

Countries can do this if they strengthen domestic tax systems by broadening the tax base and improving tax compliance. To generate additional revenue quickly, many countries are considering raising taxes on tobacco. This approach may provide additional revenue in the short term, but such taxes are not a long-term solution: consumption will likely decline over time—a primary goal of the tax. Ultimately, the objective should be less dependence on donor funds for the health sector.

At the international level, donors should align their efforts with countries’ priority of universal health coverage. This can significantly improve the coordination of disease-specific vertical health funds, allowing gradual expansion of benefits and less spending inefficiency. The medicine is not new: the 2005 Paris Declaration aims to improve the impact of aid and could provide the necessary framework to align donor activities with national health strategies. (Tensions, though, are always likely because donors often favor vertical funds that demonstrate results to their own legislators and other stakeholders.)

A permanent global health and finance coordinating body would be another step toward improving coordination and accountability. The Group of Twenty Joint Finance and Health Taskforce, established in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, is a model for such a body. It brought together finance and health ministries and key global health actors, which led to better coordination and helped reduce duplication. Together with the World Bank and World Health Organization (WHO), a permanent coordinating body would be a forum for dialogue, collaboration, and transparency between global health and finance stakeholders.

Sustainable systems

This coordination should also include better procurement. Pooled systems for donor funds can reduce inefficiency and strengthen receiving countries’ public financial systems and procurement capacity.

Consolidation could start with organizations such as the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization and the Global Fund, which could adapt their reporting systems to use pooled procurement effectively. Over time, this approach could include other key donors, such as UNICEF, WHO, and entities mandated to procure health products.

To complete the treatment, finance and health ministries must understand why it can be difficult to spend budgets they already have. The IMF and multilateral development banks provide assistance to strengthen public financial management broadly, but they should emphasize better budget execution within the health sector. A finance minister probably won’t raise the budget allocation if a health minister cannot spend the existing budget.

Most low- and middle-income countries are well behind their health-related Sustainable Development Goals. Maternal mortality remains high: over 287,000 women died from pregnancy and childbirth complications in 2020. Child mortality reductions are too small to meet targets, and preventable problems such as neonatal conditions, pneumonia, and diarrhea still led to nearly 5 million deaths in 2022. Despite available low-cost, effective technologies, 59 countries are expected to miss the target for under-five child mortality.

The global health community can ditch the status quo and chart a new course toward integrated, sustainable health systems aligned with broader economic and development goals. Commitment and collaboration will build a healthier, more equitable world for all.

Loading component...

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect IMF policy.