Sliding property prices may presage a painful economic adjustment

Are China’s real estate problems different? When we published our paper “Peak China Housing” (based on pre-COVID data) in 2020, our thesis—that China was facing a difficult transition from real-estate-led growth to more balanced growth—was far out of consensus. Most experts believed that any slowing of China’s property price and construction boom would be very gradual, with little impact on trend growth.

True, China’s house prices had risen tenfold since the early 1990s—an order of magnitude greater than the housing price increases experienced by Ireland, Spain, and the United States in the run-up to the 2008–09 global financial crisis. But China’s prices were growing from an extremely low base, with the price of a one-bedroom apartment in the center of Beijing still only 25 percent of a similar apartment in Manhattan. Moreover, the Chinese economy had enjoyed spectacular growth for four decades, and most experts were projecting only a modest slowdown.

Real estate bubbles have played a central role in postwar financial crises, not only in Europe and the US but also in East Asia and Japan in the 1990s. This Time Is Different (Reinhart and Rogoff 2009) showed the remarkable quantitative similarities in the aftermath of financial crises across time and across countries, not only in the effects on real estate prices, but on growth, unemployment, stock prices, and public debt. Although many researchers have since explored alternative approaches to marking the onset of crises, focusing mainly on growth, few have challenged that book’s broader narrative on the economy-wide effects of credit-fueled real estate bubbles.

Chinese exceptionalism

Yet most researchers and commentators argued that China was different, on top of its extraordinary growth trajectory. For one thing, learning from Western financial crises, Chinese policymakers adopted much more stringent rules on down payments, typically requiring 30 percent or more. Before the subprime mortgage crisis in the US, banks sometimes dropped the down payment requirement entirely. With rising prices, borrowers would have substantial equity in their homes after a few years anyway, or so the theory went.

Equally important, China’s government had consistently shown enormous competence and flexibility in dealing with financial problems, for example in sorting out the corporate bankruptcies that had occurred in the 1990s following the unification of China’s exchange rate regime in 1994.

After all, one of the reasons that financial crises lead to such deep and lingering effects on growth is that it can take years to apportion the losses from bankruptcies after real estate prices drop. With its strong central government, China could be expected to shortcut such problems.

Last but not least, restrictions on the range of assets that Chinese citizens are allowed to hold could be expected to continue channeling a large percentage of wealth into housing.

What then were some indicators five years ago that a real estate problem might be brewing, with broad systemic implications, even if it did not take the form of a conventional Western-style financial crisis? There were many.

First, home-price-to-income ratios in Beijing, Shenzhen, and Shanghai had reached levels nearly double those of London and Singapore, and three times those of Tokyo and New York. There is no question that in the long run, apartment costs in China’s marquee cities should have been on par with those in other great cities of the world, but prices seemed to be getting ahead of themselves.

Second, the pace at which Chinese households have been taking on debt is remarkable, with the household-debt-to-GDP ratio tripling from less than 20 percent in 2008 to more than 60 percent by 2023.

And third, inequality in China had risen (like everywhere else), so that many families were starting to hold multiple homes that lower-income families could not necessarily afford to rent. Our paper pointed to many other factors as well.

Diminishing returns

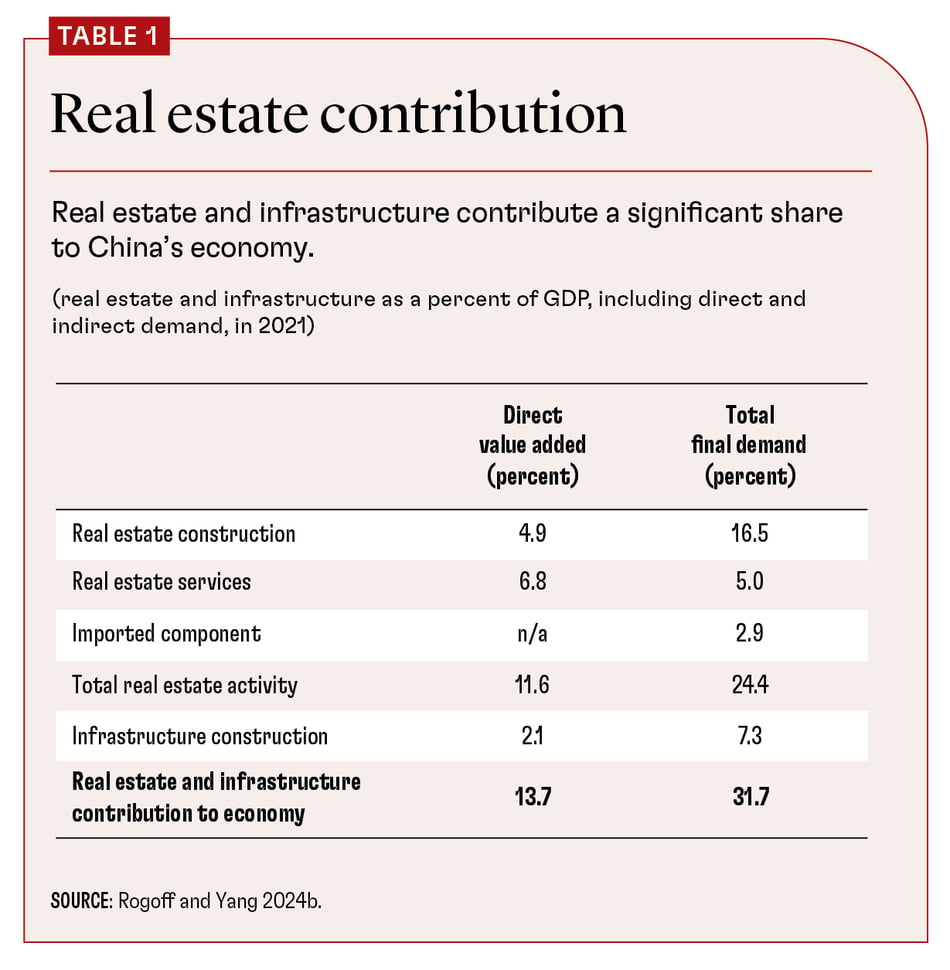

The most powerful argument, though, was evidence suggesting that China might be running into diminishing returns. As Table 1 illustrates, real estate, including both residential and commercial real estate—and taking into account both direct and indirect demand—accounted for 25 percent of China’s economy in 2021 (about 22 percent excluding imported content). The share rises to 31 percent if infrastructure is included. This far exceeds the United States (18 percent combining real estate and infrastructure) and rivals Spain and Ireland at the peak of their construction booms.

The issue is not only the scale of current construction, but also the fact that it comes on top of two decades of rapid buildup, particularly since 2010, when China’s much-lauded stimulus plan to counter the global financial crisis turbocharged the construction sector.

Anyone who has traveled to China is aware of its world-class infrastructure, even in its outermost provinces. The buildup of real estate across small and medium-size cities in China is remarkable both in quantity and quality. Indeed, per capita housing space in China now exceeds that of any major European country, even though China’s per capita GDP is only a third as high.

Even five years ago, it should have been clear that a significant adjustment was inevitable, or at least so we suggested. But some scholars countered that China’s adjustment to a smaller real estate sector could in principle be very gradual, if resources were deployed for rebuilding substandard housing over a period of decades.

This view does not stand up to scrutiny, however. Much of China’s housing is relatively new at this stage, and many of the dilapidated units are in parts of the country where the population has long been shrinking.

More recently, others have suggested that China can repurpose its construction sector to deal with the green transition. But real estate and its related sectors, which account for about 15 percent of employment, are just too big to be easily absorbed elsewhere.

In fact, very few countries have found it easy to maintain growth when the real estate sector runs into trouble, often leading to a financial crisis. Singapore is perhaps an exception. But the city-state is a small open economy with a population less than half a percent of China’s.

China can also build up its exports. One would think that countries serious about the green transition would welcome its low-cost electric vehicles. However, geopolitical frictions and populist politics in the US and Europe make this shift difficult.

City-by-city approach

What evidence is there that China’s slowing growth has actually been the result of diminishing returns and not, say, of recovery from the pandemic? Looking at detailed city-by-city growth and real estate investment data, and constructing measures of cumulative real estate construction, it’s possible to test the diminishing returns effect over time and space.

We did this in a November 2024 paper, making use of appropriate instruments and controls. We found that cities that have already substantially built up their real estate stock do indeed gain significantly less benefit from new real estate investment. These cities have also had greater problems with high local government debt, in part because growth has not come to offset the investment costs.

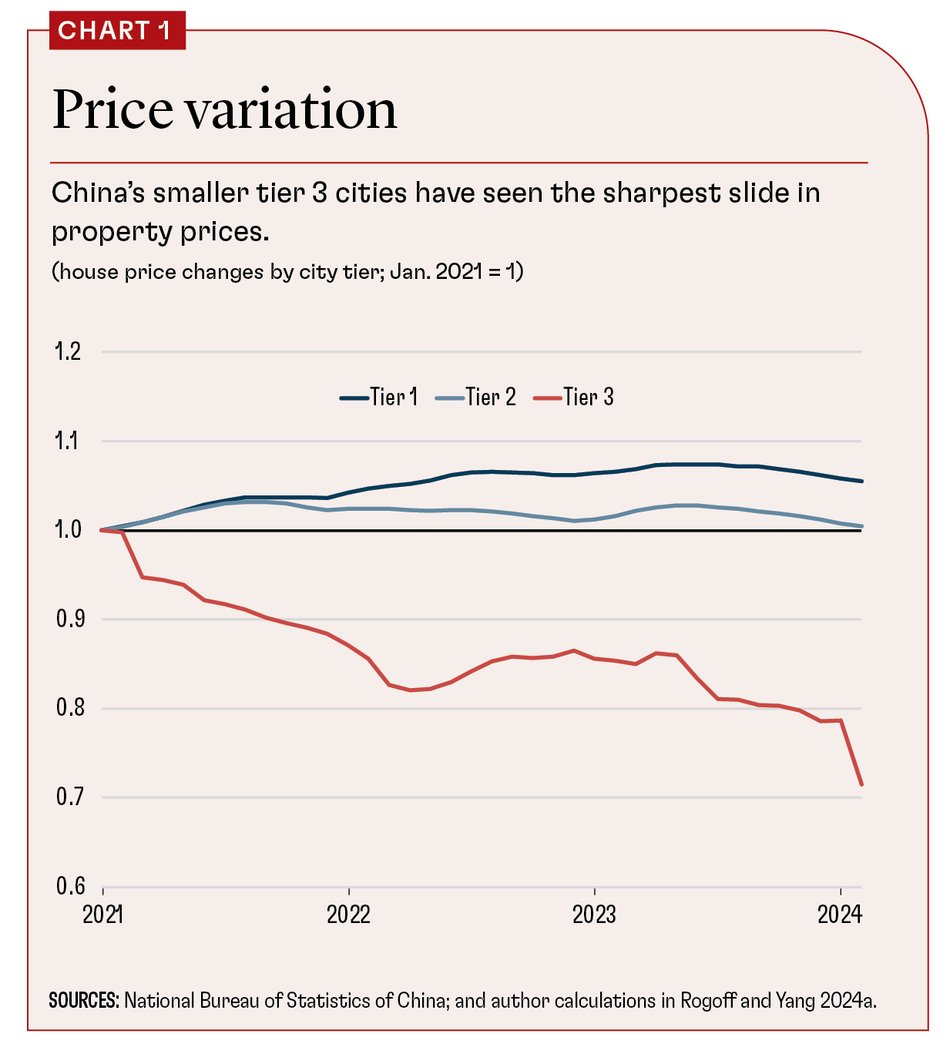

As Chart 1 shows, our calculations make it possible to compare the evolution of prices over the past couple years across China city groupings, where tier 1 cities correspond to Beijing, Shenzhen, Guangzhou, and Shanghai and tier 2 cities are provincial capitals and administrative cities, while tier 3 cities represent the smaller and generally poorer cities.

Prices in tier 3 cities, which account for 60 percent of China’s GDP, have been falling. It’s quite normal for real estate problems to be concentrated in certain parts of the country. During the US subprime financial crisis, for instance, the problems were acute in only four or five states. However, this still led to a banking crisis that spread across the country.

By the same token, not all China’s tier 3 cities have been experiencing real estate collapses. Some smaller cities, in the south especially, are thriving. A great many others, though, are suffering from an exodus of young people and jobs.

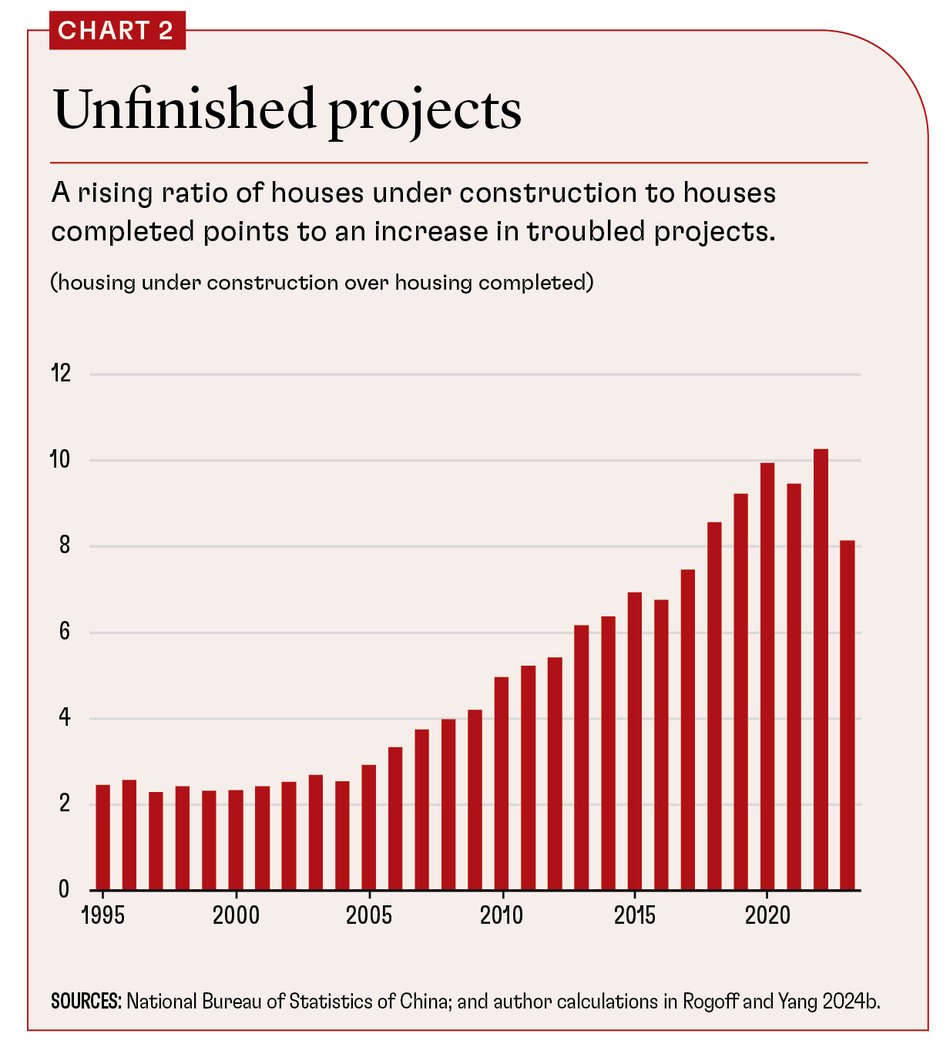

Chart 2 shows another measure of strain, the ratio of construction projects outstanding in a given year to completed projects. The rising ratio over time suggests an increase in projects going into default, buyers pulling out, or properties under dispute. We have concentrated on real estate, but there are many measures suggesting that infrastructure is also overbuilt in some parts of China.

Difficult transition

All this points to the difficulties of the transition out of real estate, even without a Western-style financial crisis. Our original 2020 paper, based on aggregate input-output data, calculated that a 20 percent fall in the size of China’s real estate sector would lead to a 5–10 percent fall in output, cumulatively over a number of years, even absent a financial crisis.

Our more recent work, based on growth regressions covering about 300 Chinese cities, shows that diminishing returns on real estate can account for perhaps 2 percent of the slowdown in China’s growth rate. Again, this finding does not take into account financial problems such as the fragility of local government debt, or the effects on consumption if housing prices fall further, so it should be considered a lower bound on the potential growth impact.

We will not speculate here on policy going forward, although it appears that a loss of confidence in real estate has significantly impacted consumption, and that the financial problems facing local governments are formidable. Regardless, it is now painfully clear that China is not as different as most scholars still thought just five years ago. Like many other countries in the past, it too is facing the difficult challenge of countering the profound growth and financial effects of a sustained real estate slowdown.

Loading component...

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect IMF policy.

References:

Reinhart, Carmen, and Kenneth Rogoff. 2009. This Time Is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Rogoff, Kenneth, and Yuanchen Yang. 2020. “Peak China Housing.” NBER Working Paper 27697, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA.

Rogoff, Kenneth, and Yuanchen Yang. 2024a. “A Tale of Tier 3 Cities.” Journal of International Economics 152 (November): 1–27.

Rogoff, Kenneth, and Yuanchen Yang. 2024b. “Rethinking China’s Growth.” Economic Policy 39 (119): 517–48.