F&D Special Feature: Africa at a Crossroads: Learning from the Past and Looking to the Future

Governments that fail to overhaul taxing, spending, and borrowing could face electoral backlash

Weak public finance management systems are a significant impediment to economic growth and development in African states. On the revenue side, many African countries underperform on tax collection. In 2018, the average tax collection as a share of gross domestic production in Africa was 16.5 percent--varying from 6.3 percent in Nigeria to 32.4 percent in the Seychelles. On the spending side, weak legislative oversight means that budget appropriation, implementation, and oversight often reflect the priorities of the executive branch. The result: only some of the revenue collected in African states actually reaches the public in the form of public goods and services. Much gets lost to spending on poorly planned “white elephant” projects, corruption, and general waste. As for borrowing, recent increases in public debt in a number of African countries have raised concerns about a lack of transparency and accountability.

Loading component...

Addressing these problems will require more than technical fixes to the operations in African treasuries. This is because at their core, public finance management systems reflect societies’ implied fiscal pacts. Thus, reforms should reflect the emerging electoral fiscal pact in African states. An important feature of this fiscal pact is the expectation that to legitimately stay in power or win elections, politicians must invest in visible and attributable public goods and services. In African democracies and non-democracies (electoral autocracies) alike, electoral competition (however imperfect) has created increased demand for roads, electricity, public schools, accessible healthcare, agricultural subsidies and extension services, social protection, and other public goods and services. The experiences of many African countries over the last two decades have strengthened this implied fiscal pact. For example, the region’s successes with universal primary education under the millennium development goals have created enormous public demand for secondary and tertiary education.

Power to the people

How will African countries sustainably finance the increasing demands of their citizens? Ignoring the public is not an option, so Africa’s public finance management systems can no longer focus solely on macroeconomics or insulate taxation and public spending from popular politics. Instead, political bargains – within the guardrails of constitutional order – must drive public finance management systems. To improve public confidence, taxation must be linked to the provision of public goods and services. In the same vein, to ensure that public spending reflects taxpayers’ priorities, legislators at national and subnational levels must play a leading role in budget appropriation and oversight. Finally, the policymaking process must be participatory and sensitive to country-specific political realities.

Exposing public finance management systems to full democratic expression will undoubtedly generate significant “inefficiencies.” However, these inefficiencies should be seen as features, and not bugs, of democratic public finance management. It is only through practice that African legislatures and other institutions will establish the institutional habits and norms needed to fully democratize tax administration, public spending, and oversight. The corollary of this is that circumventing legislative input into budget processes will stunt the institutional development of public finance management systems in the region – the long-run cost of which will be enormous, given the emerging public demands for goods and services. The demographic and political trends in African states suggest that unresponsive governments will increasingly come under populist pressure and if they fail to respond, risk popular revolt and removal through coups or mass uprisings.

Multilateral institutions such as the IMF have a significant role to play in fostering the democratization of Africa’s public finance management systems. As a starting point, these institutions need to have a healthy appreciation of the pressures facing Africa’s politicians. Being in the business of winning and retaining power through popular elections, politicians (in both democracies and electoral autocracies) have every incentive to support and fund easily visible projects, such as roads, schools, and hospitals. To put it simply, ribbon-cutting is the main currency of electoral politics. Therefore, technical assistance from the IMF must strive to be compatible with the perspectives and incentives of pivotal political figures. It is not enough to offer orthodox reforms borne of ignorance of local contexts, watch them fail, and blame “a lack of political will.” Taking politicians’ incentives seriously must be a core part of technical engagements.

Additionally, country engagements must not begin and end with the executive branch. In addition to interfacing with treasuries and central banks, multilateral institutions should meet regularly with legislatures and other relevant players in African states. Many African countries have laws mandating legislative input in taxation, budget appropriation, debt procurement, and other public finance management system functions. The IMF and other multilateral institutions should leverage these statutory requirements to build strong, meaningful relationships with legislators. During country visits, it’s not enough to meet only with the speaker of the legislature. The relationships must be broader and deeper, including with members of committees in charge of taxation, appropriation, and core spending sectors such as agriculture, education, healthcare, and infrastructure. Regular meetings with legislators will help officials at multilateral institutions better understand local political dynamics, thereby increasing the odds that technical assistance programs and proposed reforms are politically feasible.

Changing perceptions

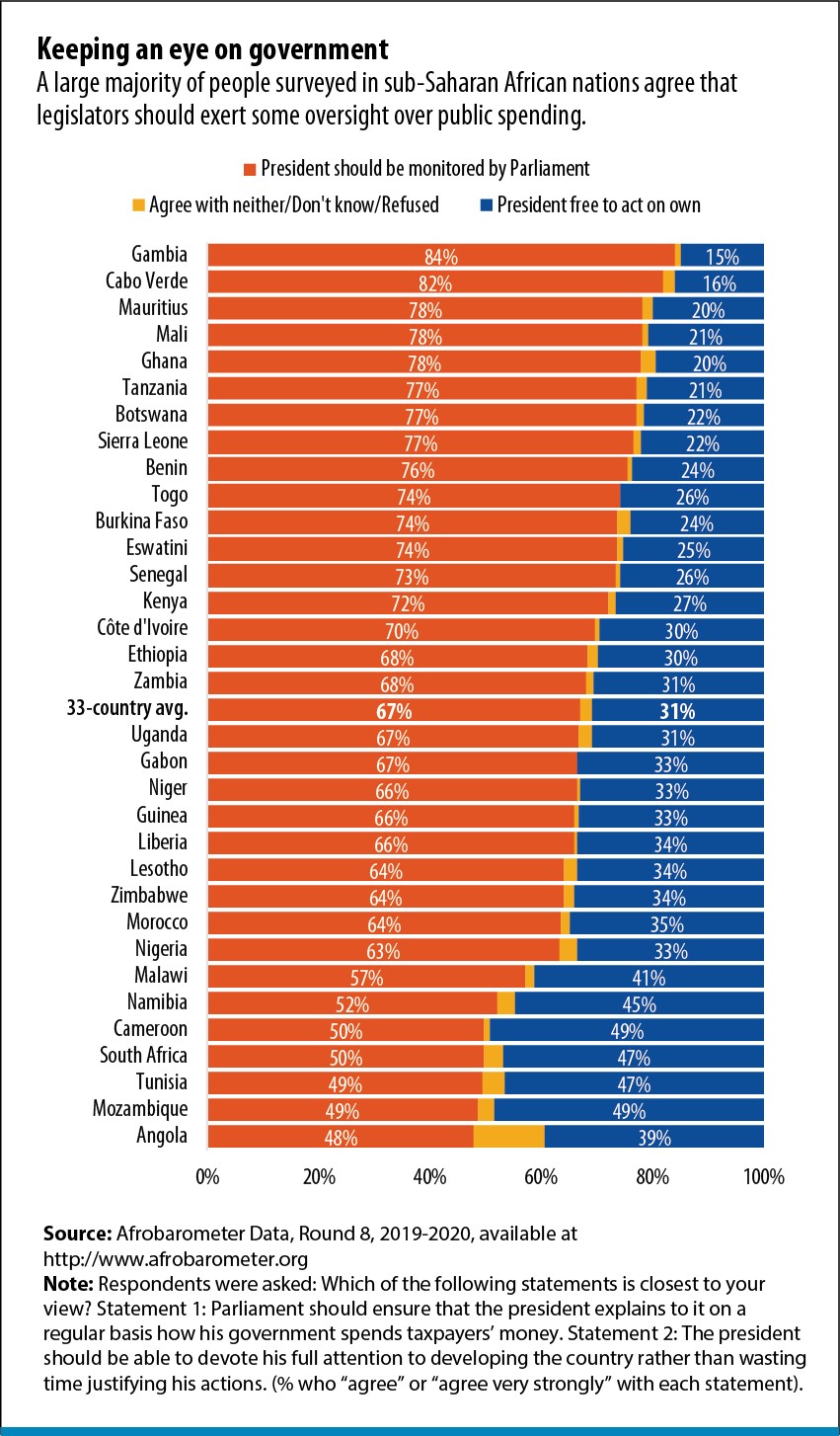

Perceptions and ideas also matter. Most citizens of African countries view public finance management system operations as either opaque, corrupt, or both. For example, in Round 7 of the Afrobarometer Survey (2016-18) of thirty-four countries, only 36.1% of respondents approved of government performance on corruption. In a similar survey, a clear majority of respondents agreed that the president should be monitored by the legislature (see chart). Addressing this will require more than general anti-corruption efforts. Instead, reforms must target public perceptions and understanding of the core drivers of corruption – including low budget absorption capacity, political cronyism, and the essential features of the electoral exchange between politicians and voters. Instead of treating corruption as a moral or legal problem, reformers should recognize the relationship between certain kinds of corruption and distributive politics. This means understanding the relationships between public sector corruption and private sector lobbying, campaign finance, constituent service, and intra-elite political payments that are critical for state stability. Doing so would enable reformers separate “transaction costs” corruption that can be legitimized through legislation and regulation (as is the case in many consolidated democracies) from run-of-the-mill theft of public resources.

Idea-driven engagement is sorely needed in policy analysis and development. Public spending in many African countries often faces popular pressure from disparate geographically concentrated ethnic/regional interests with varied (and often conflicting) ideas about what it means to invest in “development.” This calls for investments in local policy think tanks, especially on the most productive ways of spending scarce resources. The advantage of generating policy ideas locally is that such policies are more likely to be tailored to – and representative of –local demands. Multilateral institutions can then build relationships with these embedded think tanks as a way of maximizing their policy influence.

Given Africa’s demographic and political trajectories, the challenges confronting its public finance management systems will only get tougher. Rising populations, rapid urbanization, and increasing electoral competition will exert enormous pressure on governments to increase spending on public goods and services. Cognizant of the need to maintain macroeconomic stability, it will be tempting to insulate the region’s public finance management systems from political demands. Yet for all the reasons articulated above, that approach is likely to result in failure. It is only through a tight embrace of politics and institutional processes that African countries will succeed in building strong democratic public finance management systems that are responsive to the needs of their respective populations.

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily represent the views of the IMF and its Executive Board, or IMF policy.