Empowering Women Could Boost Fertility, Economic Growth in Japan and Korea

May 21, 2024

Creating a supportive environment for women through family-friendly policies, flexible labor markets, and progressive social norms will yield economic gains

Women in Japan and Korea face especially tough challenges juggling career and family. Many young women witness their peers encountering promotion delays after marriage and childbirth, dealing with problems splitting housework responsibilities, and having difficulty finding adequate childcare. The financial burden associated with raising children, including the costs of larger living spaces and ensuring a competitive education for their offspring, is an additional factor affecting couples’ decisions on whether to expand their families.

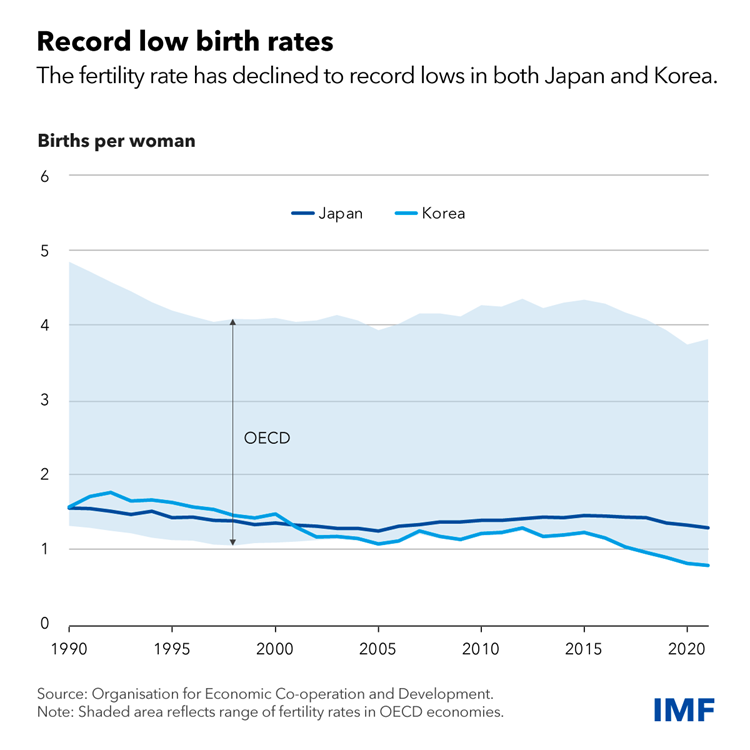

Consequently, later marriages and childbirth have become increasingly more

common, contributing significantly to declining fertility in these two

countries. At 0.72 and 1.26, respectively, the latest fertility rates in

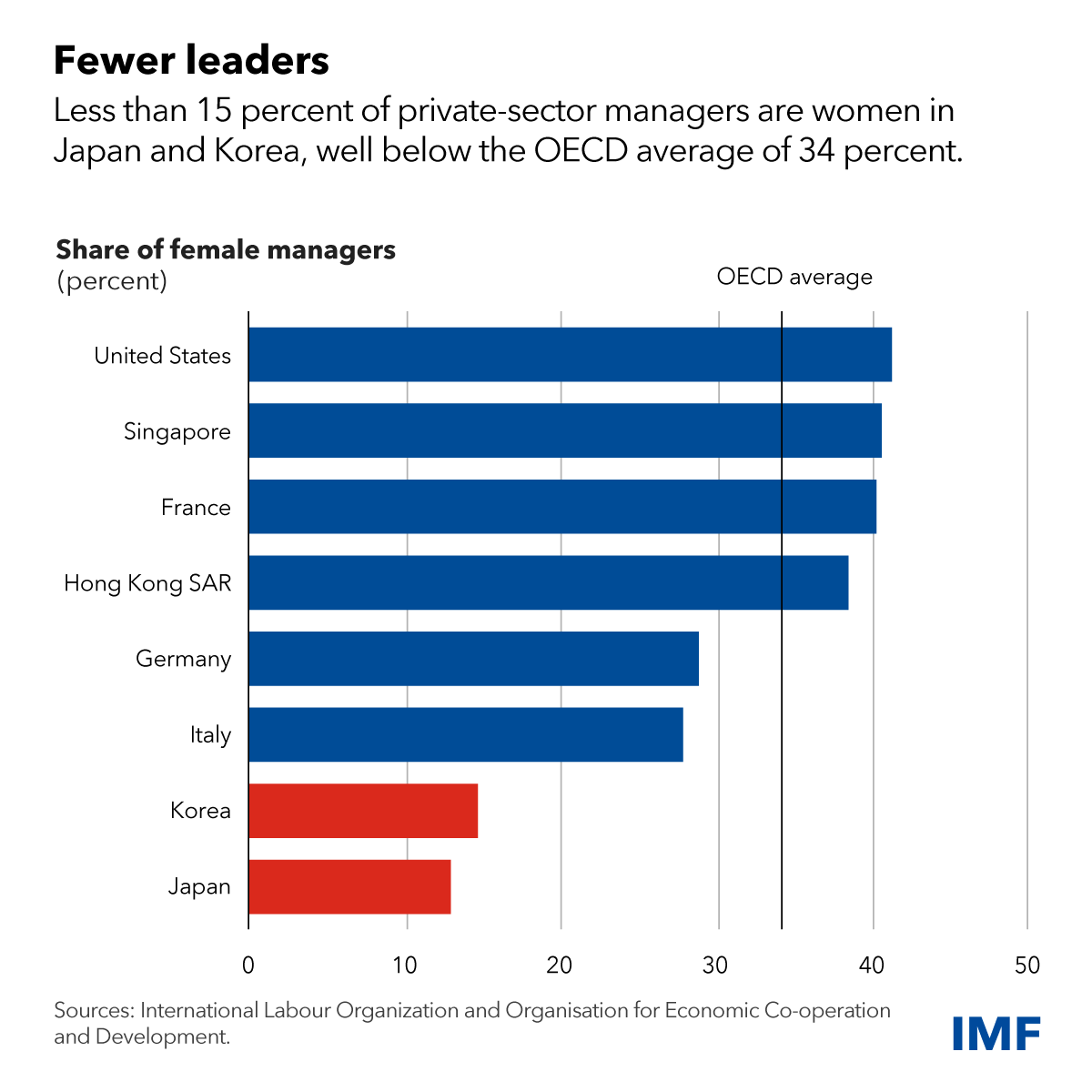

Korea and Japan are among the lowest in the world. Meanwhile, large gaps

between men and women still exist in employment and wages, particularly for

leadership positions. Representation of women in senior management roles is

less than 15 percent in both Japan and Korea, among the lowest in G20

countries. What are some of the conditions in and outside the workplace

that contribute to low fertility and large gender gaps for both countries?

Social norms in these two countries place a heavy burden on women. Women in Japan and Korea perform approximately five times more unpaid housework and caregiving than men, more than double the OECD average for gaps between men and women in unpaid work. Fathers in these two economies take less paternity leave compared with those in peer economies, despite more generous benefits.

Furthermore, something known among economists as “labor market duality” disproportionately affects women. In both countries, this means that a large share of women workers hold temporary, part-time, or other types of “non-regular” positions with low wages and limited opportunities for skill development and career advancement. In particular, some women who left the labor force (departing jobs with regular hours and benefits) during the early years of their kids’ childhood could only return to “non-regular” positions. Seniority-based promotion systems further penalize mothers who return to work.

Finally, working arrangements in these countries are often not family-friendly. Long working hours, inflexible schedules, and limited use of telework in Japan and Korea make balancing career and childcare responsibilities extremely challenging for women.

The governments of Japan and Korea have acted to support women, including through enhanced childcare and maternity leave policies, but more efforts are needed from these governments, business communities, and society at large:

First, reducing “non-regular” employment conditions, encouraging merit-based promotions, and facilitating more job mobility can help support more employment and career growth opportunities for women. A recent IMF analysis on Korea estimates that reducing severance payments for regular workers (which eases dismissals and facilitates labor reallocation for both men and women) by 30 percent alone can significantly increase labor force participation among women and productivity growth (by 0.9 and up to 0.5 percentage point, respectively).

Work discouraged

The productivity gains could be further increased if complemented with measures to support career development and facilitate job mobility for women. The net impact on male workers is also positive due to a more effective allocation of labor. Recent IMF research on Japan suggests that various distortions in Japan’s tax and social security system discourage second-income earners—a large portion of employed women in the country—from working more.

Second, further expanding childcare facilities and facilitating fathers’ contributions to home and childcare, including establishing stronger incentive mechanisms for paternity leave use, are crucial. Japan’s fertility rate mostly stabilized after the country expanded childcare facilities over a decade ago, and recent IMF studies on Japan confirm that increasing such facilities further would have a positive impact both on fertility and women’s career advancement.

Third, facilitating a cultural shift in the workplace by expanding the use of telework and flexible working-time arrangements could support increased women labor participation, while also allowing men to share more responsibilities at home.

Rising female labor force participation has already contributed to the post-pandemic growth recovery in Japan and Korea, while significant gains would result from further closing the gender gap. IMF analysis suggests that policies that reduce Korea’s gap between men and women in hours worked in to the OECD average by 2035 can boost the country’s per capita GDP by 18 percent compared with no change. Another IMF study shows that bridging Japan’s large gap in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) fields can boost the country’s total factor productivity growth by 20 percent and social welfare by 4 percent.

In Japan and Korea, policies aimed at closing gender gaps and progressively shifting cultural norms will help increase the growth potential, despite demographic headwinds. They also can help gradually reverse declining trends in fertility, allowing women in Japan and Korea to manage having a family while pursuing fulfilling careers, and, in turn, to contribute significantly to their economies and societies.

****

— Kohei Asao, TengTeng Xu and Xin Cindy Xu are economists in the IMF’s Asia-Pacific Department. For more information, see recent see recent Korea Country Report Annex XII, “Addressing Gender Gaps in the Labor Market”, prepared by Jorge Mondragon and Eonyoung Park, selected issues papers on Structural Barriers to Wage Income Growth in Japan, Women in STEM Fields in Japan, Japan’s Fertility: More Children Please, and Why So Few Women in Leadership Positions in Japan?