Five country cases illustrate how best to improve tax collection.

A typical developing economy collects just 15 percent of GDP in taxes, compared with the 40 percent collected by a typical advanced economy. The ability to collect taxes is central to a country’s capacity to finance social services such as health and education, critical infrastructure such as electricity and roads, and other public goods. Considering the vast needs of poor countries, this low level of tax collection is putting economic development at risk.

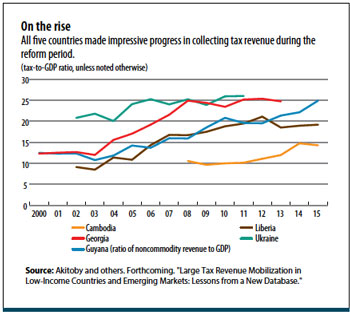

How can policymakers tackle this challenge? A look at successful reforms between 2004 and 2015 in five low-income and emerging market economies—which achieved some of the largest revenue gains after tax reform—offers some answers. The experiences of this diverse set of countries—Cambodia, Georgia, Guyana, Liberia, and Ukraine—show that, regardless of the constraints they face, countries can strengthen their capacity to collect tax revenue by pursuing reform strategies with certain distinct features. We focus here mainly on Georgia. By analyzing what worked in that country we can draw lessons for what strategies other countries should consider.

Georgia offers a striking example of successful tax revenue reform. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the government struggled to collect tax revenue. By 2003, rampant corruption involving tax evasion, illegal tax credits, and theft of government tax revenue had left public finances in shambles. The government was no longer able to honor its obligations to public servants and pensioners, even though salaries and pensions were very low.

Georgia’s sweeping tax reform was made possible after the 2003 Rose Revolution, which gave the new government a mandate to reform the economy and fight widespread corruption. The country’s new leaders adopted a policy of zero tolerance for corruption, and the culture began to change, along with the laws. A revised tax code, passed in 2004, simplified the tax system, reduced rates, and eliminated a series of minor local taxes that had been generating little revenue (on pollution and gambling, for example). Only 7 of 21 taxes remained, and many of the rates were reduced.

Progressive personal income tax rates (12 to 20 percent) were replaced with a flat rate of 20 percent, and the social security contribution tax rate was first reduced from 33 percent to 20 percent and then eliminated altogether. Corporate income was taxed at a flat rate of 15 percent, and the value-

added tax (VAT) was reduced from 20 percent to 18 percent. The revenue lost from lower tax rates was made up through a broader tax base, better compliance, and stricter enforcement.

The government also made it easier to pay taxes by introducing measures such as an electronic tax filing system. In this way, technology both improved efficiency and reduced opportunities for corruption. In parallel, the government lowered the minimum capital required to start a business, which also generated more tax revenue.

The improvement in the country’s ability to mobilize revenue between 2004 and 2011 is all the more impressive given the sharp reduction in tax rates. By 2008, Georgia’s tax-revenue-to-GDP ratio had doubled to 25 percent.

Lessons for tax reform

What does Georgia’s experience teach us about how best to increase tax revenue? While there is no one-size-fits-all solution, there are a few lessons that can be drawn from Georgia’s case as well as the experiences of the other four countries.

Have a clear mandate. Governments with a clear mandate to reform the tax system often succeed. Georgia’s comprehensive tax reform was feasible only after the country had reached a high degree of dysfunction, triggering a revolution. Similarly, in Ukraine, the 2004 Orange Revolution was a catalyst for tax reform. And in 2003, Liberia initiated reform after the civil war had ended.

Secure high-level political commitment and buy-in from all stakeholders. While a clear mandate is necessary, it is not sufficient. Many newly

elected governments do have such a mandate, but not all of them reform. Therefore, political commitment at the highest level and broad buy-in are needed. Social dialogue enhances the likelihood of reforms being implemented and sustained. Effective communication with stakeholders that emphasizes the intended benefits of reforms can help overcome resistance of vested interests. And compensating the losers has proved effective in winning public support for tax reform initiatives.

Simplify the tax system and curb exemptions. A simpler tax system with a limited number of rates is critical to fostering taxpayer compliance, as seen in the Georgia example. Notably, in fragile states, focus first on simplifying taxes, procedures, and structures. Simplicity of the tax system and legislation is the guiding principle for fragile states. This makes tax administration less challenging in weak states that lack such basic institutions as security and a well-functioning judicial system.

Liberia is a case in point. Following its emergence from civil war, Liberia introduced taxes on turnover or import values, such as the goods and services tax, excises, and customs tariffs, underpinned by simple tax legislation.

Curbing exemptions can also reduce the tax system’s complexity while boosting revenue by broadening the tax base. Many countries incur a sizable loss of revenue through ill-designed exemptions, such as costly tax holidays and other incentives that fail to attract investment. And discretionary granting of exemptions provides opportunities for corruption.

Reducing exemptions figured prominently in nearly all five countries. Guyana, for example, implemented a comprehensive exemption reform with main elements that included eliminating the power of the finance minister to grant discretionary exemptions, publishing exemptions annually, and limiting income tax holidays to every 5 or 10 years, depending on the sector.

Reform indirect taxes on goods and services. The VAT has proved to be an efficient and strong revenue booster: countries that impose this tax tend to raise more revenue than those that don’t (Keen and Lockwood 2010). In addition to reducing the rate, Georgia streamlined its VAT refund mechanism, allowing revenue from this source to rise from 8.5 percent of GDP in 2005 to about 11.5 percent in 2009.

Guyana successfully introduced a VAT on January 1, 2007, despite significant challenges in the preparatory work, including setting up the new VAT department with fully trained staff, putting in place the supporting IT system and procedures, and training potential registrants and practitioners. The VAT was broad-based, with a single rate of 16 percent and a limited number of exemptions for financial, medical, and educational services. As part of its reform, Ukraine also curbed VAT exemptions and revised the regime for agriculture by reducing the rate and eliminating refunds.

Increases in excise and sales taxes are the simplest measures because they can raise revenue fairly quickly without fundamental changes to the tax system. For example, Guyana in 2015 took advantage of the decline in the international price of oil to raise fuel excise taxes. This step buoyed revenue during the country’s economic slowdown. Similarly, Liberia broadened the scope of its goods and services tax while raising excise taxes on alcoholic beverages and cigarettes.

Introduce comprehensive tax administration reforms. Successful revenue mobilization cases tend to take a more holistic approach to modernizing tax institutions. In all five case studies, revenue administration reforms figured prominently and covered a broad spectrum of legal, technical, and administrative measures, such as

Management, governance, and human resources: Four of the five countries implemented some management and governance changes. Georgia gradually recruited new tax and customs officers and phased out the old ones as part of its anti-corruption reform.

Establishment of large taxpayer offices: A large taxpayer office allows a country to focus tax compliance efforts on the biggest taxpayers, as Cambodia has done. These offices also support good tax administration; they often pilot new tax and customs procedures before their rollout to the broader population.

Smart use of information management systems: Successful revenue mobilization hinges on managing information and leveraging the power of big data to improve compliance and fight corruption. Most of the countries studied have taken advantage of IT systems to leapfrog their revenue mobilization reforms. Georgia has automated most processes, including e-filing. It has also instituted a system for information sharing among tax authorities, taxpayers, and banks, as well as a one-stop Internet portal. Cambodia, Guyana, and Liberia have likewise computerized the administration of their taxes and customs.

More modern registration, filing, and management of payment obligations: All five countries have sought to establish or modernize basic rules and processes in these key compliance areas. For instance, Guyana implemented a unique system of taxpayer identification numbers and streamlined its process. It also introduced income tax withholding, a measure critical to fostering compliance.

Enhanced audit and verification program: A risk-based audit, which links the likelihood and nature of an audit to the taxpayer’s inherent risks, is the most effective type in terms of encouraging compliance. All five countries have made this a key part of their revenue mobilization strategy. Notably, Cambodia conducted risk-based audits of taxpayers at customs and of the 150 largest taxpayers and hired some 200 new auditors. Ukraine implemented a targeted audit program, improved the internal control of tax administration, fought fraudulent VAT claims, and developed an anti-smuggling program at the customs office.

Taking the long view

Although the optimal timing and design of reform measures vary among countries, these five cases highlight some basic lessons. One such lesson is that countries that pursue revenue administration measures and tax policy reform in tandem tend to see much larger gains.

But countries must give tax reform time to bear fruit. The duration of the reform episodes ranged from two to seven years. Sustained success requires institutional change, which happens only gradually.

The revenue increase in each of the five countries was impressive and averaged at least 1 percent of GDP a year over the reform period (see chart). This is consistent with the quantitative tax revenue objective over the four- to six-year time horizon recently advocated by the IMF’s Vitor Gaspar and Abebe Selassie. In Georgia, the revenue gains averaged 2.5 percent of GDP a year, as was the case in Ukraine. Moreover, all five countries sustained the revenue gains in the five years after the reform episodes, confirming the quality of the measures put in place.

These five cases clearly show that large tax revenue mobilization can be achieved and sustained. Although reform must be tailored to individual circumstances, three lessons stand out: tax reform requires first and foremost a broad social and political commitment; it rests on broad-based strategies that recognize that what and whom to tax should go hand in hand with how to tax; and it should be developed with the longer view in mind.

This paper draws on a forthcoming IMF Working Paper, “Large Tax Revenue Mobilization in Low-Income Countries and Emerging Markets: Lessons from a New Database,” by Bernardin Akitoby, Anja Baum, Clay Hackney, Olamide Harrison, Keyra Primus, and Veronique Salins.

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect IMF policy.

References:

Gaspar, Vitor, and Abebe Aemro Selassie. 2017. “Taxes, Debt and Development: A One-Percent Rule to Raise Revenues in Africa.” IMF blog. https://blogs.imf.org/2017/12/05/taxes-debt-and-development-a-one-percent-rule-to-raise-revenues-in-africa

International Monetary Fund (IMF). 2015. “Current Challenges in Revenue Mobilization: Improving Tax Compliance.” IMF Policy Paper, Washington, DC.

— — — . 2017. “Building Fiscal Capacity in Fragile States.” IMF policy paper, Washington, DC.

Keen, Michael, and Ben Lockwood. 2010. “The Value-Added Tax: Its Causes and Consequences.” Journal of Development Economics 92 (2): 138–51.

World Bank. 2012. Fighting Corruption in Public Services: Chronicling Georgia’s Reforms. Washington, DC.