Typical street scene in Santa Ana, El Salvador. (Photo: iStock)

IMF Survey : Emerging Markets Show More Resilience to Capital Flow Cycle

April 6, 2016

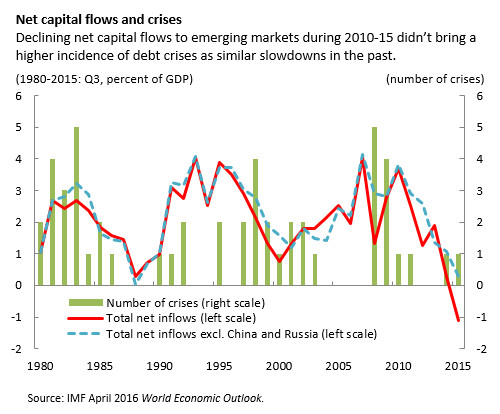

- Net capital flows to emerging market economies slowed significantly since 2010

- Slowdown associated with decline in growth prospects, but without resulting in high incidence of debt crises as in past

- Greater exchange rate flexibility, foreign reserves, and lower public debt can help

Despite lower capital inflows and higher capital outflows since 2010, emerging market economies have remained resilient.

Declining net capital flows to emerging markets reinforces the need for continued policy upgrade in emerging market economies (Illustration: Konstantin Inozemtcev)

WEO ANALYTICAL CHAPTER

A new study, published in the IMF’s April 2016 World Economic Outlook report, takes a closer look at more than 40 emerging market economies to understand the drivers of declining capital flows since 2010.

The analysis also examines the modest impact of the declines compared to earlier episodes in the 1980s and 1990s, when prolonged downswings in capital flows resulted in a higher incidence of financial and debt crises. The study looks at one episode of slowing capital inflows, from 1981-85, which coincided with the developing country debt crisis, and another from 1995-2000 which overlapped with the 1997-98 Asian financial crisis. Capital flows refer to all financial flows—bank, foreign direct investment, and portfolio investment between residents and non-residents.

The study finds that a considerable portion of the decline in net capital flows— about $1.1 trillion from 2010 to late 2015—can be linked to investors’ concerns about diminished growth prospects in emerging market economies relative to advanced countries, with bouts of risk aversion and, more recently, the prospect of tighter financial conditions in some advanced economies playing a role. Yet, structural and domestic policy factors strongly determine the extent to which different countries are affected. Hence, policymakers can take action to ameliorate the effects of the expected growth slowdown on capital flows and financial stability going forward.

Emerging market resilience: now and then

Surges and declines in capital flows are hardly new. Some past downturns in capital flows have also been linked to investors’ concerns about the prospect of growth slowdowns in emerging nations—for instance, due to lower commodity prices and cyclical bouts of over-optimism and pessimism, sometimes triggered by less benign global financial conditions. Yet, the study shows that emerging market economies have so far weathered this slowdown in capital flows better than in previous cycles (see chart).

The study cites several factors for this resilience:

First, emerging market economies are more widely integrated in global capital markets, with higher foreign assets, including foreign exchange reserves, which give these economies greater latitude to manage the capital flow decline.

Second, policy frameworks in many emerging market economies have generally improved over time, reducing the effects of lower capital flows on country risk. Indeed, better debt management strategies and macroprudential policies marked a change in the currency composition of public and private debt in these economies over the 2000s. As a result, these economies have been less vulnerable to abrupt currency depreciations that could raise the foreign debt burden, and risk country insolvency. Indeed, capital flow declines in many emerging market economies in 2010-15 have been less abrupt than in previous cycles and the turnaround of external current accounts has been more gradual.

Finally, another important change has been the move to greater exchange rate flexibility, which has helped cushion the effect of a global contraction in external financing on individual economies. After all, depreciations make outflows more costly and help attract new inflows by making domestic assets cheaper to the foreign investor. At the same time, exchange rate depreciations—when they are orderly and do not take the form of abrupt adjustments, as in several crises of the past—can act as an effective shock absorber for consumption and employment, mitigating growth slowdowns and hence further drops in inflows due to heightened country risk.

In general, the analysis finds that external (“push”) factors that drive capital flows—like global growth, global risk aversion, and interest rate differentials—had less of an impact in emerging market economies with greater exchange rate flexibility.

Gearing back up

The study’s findings have salient policy implications.

Countries are not simple bystanders to the global financial cycle. The slowdown in capital flows reinforces the need for a continued policy upgrade in emerging market economies.

Specifically, prudent fiscal policies (which help lower public debt and manage it better), macroprudential policies (which help limit currency mismatches), exchange rate flexibility (which can work as a shock absorber), and prudent foreign exchange reserve management (which can help smooth bouts of investors’ risk aversion) help mitigate the contraction and the domestic spillovers of the global capital flow cycle in individual emerging market economies.

The study also highlights that increased vigilance needs to be exercised with regard to capital outflow dynamics, which can pose significant risks, but are not yet sufficiently understood.

The authors of this report are Rudolfs Bems (lead author), Luis Catão (lead author), Zsóka Kóczán, Weicheng Lian, and Marcos Poplawski-Ribeiro, with support from Hao Jiang, Yun Liu, and Hong Yang.