Women entrepreneurs are changing the dynamics of the Arab workplace

In the Arab world, women are increasingly stepping into entrepreneurial roles, asserting their influence on business and technology, and leading a quiet revolution that would have been unthinkable a generation ago. The trend marks a departure from traditional roles and gender expectations, and it could hold profound implications for the region’s development and progression toward more inclusive societies.

While the Arab world has historically seen limited female participation in the labor market, the growing presence of women in business start-ups follows a global pattern that is accelerating innovation and diversifying prosperity. It is not an instantaneous or easy transition. Addressing barriers to equality frequently means challenging social norms and confronting entrenched interests. In the Middle East and North Africa, labor force participation for women is still a meager 19 percent compared with the global average of nearly 50 percent. But across the region, opportunities are expanding, and women—like the three we profile below—are challenging patriarchal attitudes.

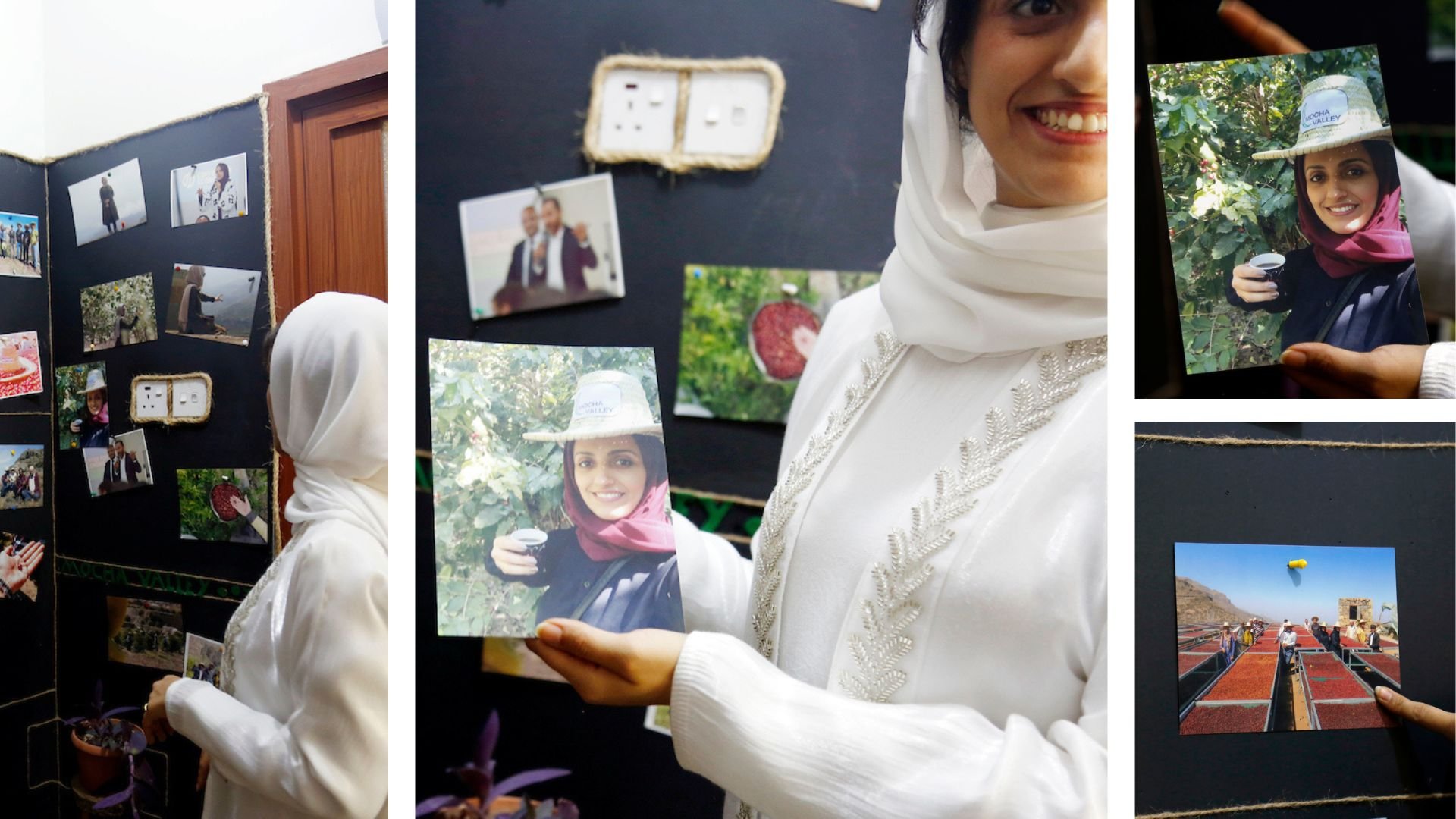

Brewing opportunities in Yemen

Arzaq Al-najjar is trying to modernize the coffee business in one of the poorest, most war-torn, and ancient coffee producing regions on Earth. From a third-floor office overlooking Yemen’s capital of Sana'a, Al-najjar, 34, runs Mocha Valley, a coffee-production and business consultancy that specializes in research, training, and development assistance for entrepreneurs, investors, coffee traders, farmers, and partners along the coffee value chain. The company takes its name from the Red Sea port of Mocha at the tip of the Arabian Peninsula—once the world’s crossroads for coffee—which in turn lent its name to the popular drink. Nearly 600 years ago coffee beans procured from Ethiopia were first roasted, brewed, and sipped in Yemen’s Sufi shrines. During the 16th century, ships laden with beans carried coffee from the port of Mocha to destinations throughout the Middle East and North Africa, and a century or so later to Europe. By the early 20th century, coffee had become a global commodity, and by 2021, coffee exports topped $36 billion.

Today, Yemen exports less than 1 percent of the world’s coffee, and Al-najjar is determined to change that. “What the Yemeni coffee industry needs is the development and expansion of its value chain,” she says. “We want the world to know about and experience this Yemeni treasure.”

Al-najjar has a unique passion for the history and importance of coffee in Yemen. She was the first female “coffee cupper,” or coffee taster, in the country, and soon after completing her MBA in Lebanon, she became a consultant to local NGOs and coffee traders. An industry organized around modern standards and better data, she says, would make it easier for Yemen’s producers and traders to reach global markets and help Yemen’s development, which ranked near the bottom (183rd of 191 countries) of the UN’s Human Development Index in 2021.

Bolstering the industry, however, is no small feat. Yemen is suffering through one of the worst humanitarian crises in the world. “Over eight years into the ongoing conflict, the Yemeni people continue to face extreme hardship. Approximately 22.5 million people, or about 75 percent of the entire population, require humanitarian assistance, with over 4.3 million civilians displaced,” the World Bank reported. The IMF estimates that Yemen’s GDP will fall by 0.5 percent in 2023 and that inflation will run at 17 percent.

Al-najjar, however, is identifying opportunities. “Coffee workers were unqualified and untrained, and we started by providing knowledge and free training to coffee workers to understand why we need quality standards in Yemen.” When she launched Mocha Valley five years ago it wasn’t easy opening doors, and it still isn’t. Yemen has a traditional culture, and women are frequently discriminated against in business. “Being a woman is such a difficulty in our society,” she says, “Yes, of course, I have been told, ‘you are a woman and you cannot lead this company.’” Businesswomen are disproportionately burdened in seemingly banal ways. “Here in Yemen most of the deals, most of the contracts happen during qat sessions,” Al-najjar explains, describing meetings in which men—and only men—negotiate transactions while chewing the leaves of the shrubby stimulant, sometimes for hours on end.

Qat also presents another set of challenges for Al-najjar and her goal of expanding coffee production. For many Yemeni farmers, qat is a more lucrative crop than coffee; as a result it siphons off farmland as wells as a great deal of water in one of the world’s most water-scarce countries.

But Al-najjar is motivated to cultivate a stronger and more resilient coffee industry in Yemen and is optimistic that it can be made more efficient with greater participation from women. She is excited by the coterie of young female leaders being cultivated in Yemen’s coffee industry and at Mocha Valley. “They say they are inspired by such a journey, and they have goals,” she says. “Maybe in the future they are going to be leaders in the coffee sector.”

Empowering Egypt’s unbanked

“Khazna was built from day one to serve the underserved,” says Fatma El Shenawy, the Egyptian fintech’s cofounder and a vocal evangelist for extending financial services to low- and middle-income families throughout the Middle East.

El Shenawy helped found Khazna in 2019, before she was even 30. Her vision was to leverage a disruptive platform to connect Egypt’s unbanked and underbanked with a fast and easy digital method of accessing their money, paying their bills, and buying services from an app on their phones.

Egypt has a staggeringly high number of people who have no access to formal banking services—67 percent of the population, according to Global Finance Magazine. But with mobile phones in more than 90 percent of the country’s households, El Shenawy and her partners saw an opportunity to connect people with a range of services. “We provide our users with an income-backed multipurpose credit line that they can use to request a cash advance, pay their bills, purchase products from our large merchant network and buy medical insurance for their families,” she says. The service has great scalability potential. The World Bank estimates that about 1.7 billion people around the world are currently unbanked.

Financial inclusion is a difficult problem to remedy, but Khazna is making inroads by partnering with a range of businesses that employ 1.5 million people, as well as working with Egypt Post to serve their 5 million pension customers. Beyond Egypt, Khazna has its sights on Saudi Arabia. “We believe Saudi and Egypt share key similarities for our business, mainly a progressive regulator that is open to new ideas and advancing financial service offerings driven by innovative solutions from new start-ups. Additionally, Saudi has a digitally connected population that is ready for new financial services,” says El Shenawy, who worked as an investment banker in Cairo for five years prior to starting Khazna.

Today, the firm has more than 350 employees. It raised $38 million in equity and debt through local, regional, and global venture capital firms last March, bringing its total funding to more than $47 million.

El Shenawy is still an anomaly in Egyptian culture, where large gender gaps remain in business and entrepreneurial activity. Labor participation is just 15.4 percent for women compared with 67 percent for men. “One of the main challenges faced by women, in my experience, is that we do not get the same level of support that our male peers receive in [their] careers, especially in entrepreneurial endeavors from their close communities,” she says. “I’m lucky to have always been surrounded by peers and mentors who support me on both the professional and personal level.”

Loading component...

Motivating Palestinian entrepreneurs

Mona Demaidi is on a mission to accelerate high-tech female entrepreneurship in the West Bank and Gaza, and her method is intensive training and personal coaching. “Most of what I am working on in the private sector,” she says, “is upscaling youth and females in technology and providing them with mentorship.” Demaidi says that a legacy of inadequate resources, narrow opportunities, insufficient cultural support, and decades of conflict have held young Palestinian women back in the workforce, in particular in the tech sector, even though half the graduates of tech-based education programs are women. To advance economic development, history shows that trend needs to be reversed, she says, and the best way is through specialized programs in safe places that can offer tools, boost confidence, and build skills. “You know,” she sighs, “we face a lot of ups and downs here.”

Demaidi is particularly concerned that the region is falling behind in AI, an important niche where female employment lags even the full sector’s 20 percent average. “The limited availability of educational programs in AI contributes to the low number of students pursuing an education in the field,” she wrote in This Week in Palestine. Only 9 percent of universities in the West Bank and Gaza offer programs in artificial intelligence, and none higher than a master’s degree. Between 2016 and 2021, all of the Palestinian territories graduated just 28 students who specialized in AI, arguably one of the hottest and most talked about industries on the globe. Because of the meager number of AI start-ups in the West Bank and Gaza—less than 1 percent (and none founded by women)—Demaidi spends significant resources cultivating AI entrepreneurship. In 2022, she developed the Palestinian National Strategy for AI, which aims to accelerate innovation and adoption.

Mona Demaidi is a bundle of energy. She splits her time between teaching at An-Najah National University, where she is an assistant professor, and running the organization Girls in Tech –Palestine, where she is the managing director. Her work has led her to develop programs that encourage women to pursue careers in the tech industry through boot camp trainings, free online courses, private sector exchanges, and open access to job boards.

While AI start-ups are rare throughout the West Bank and Gaza, a thriving start-up ecosystem composed of tech and non-tech companies has begun to emerge in recent years. Most tech companies in that category focus on e-commerce. A driving factor has been the abundant pool of talented young tech entrepreneurs freshly minted at West Bank universities every year. That ecosystem, according to the World Bank, is at an early stage but is showing great promise, in part due to coaching programs like the ones Demaidi champions. “On average, each year, 19 more start-ups are created than in the previous year, resulting in a 34 percent compounded growth rate in start-up creation since 2009.”

Mentorship, the World Bank says, has been an accelerant in the West Bank and Gaza. Nearly 40 percent of start-up founders have been mentored, and it has proved to be an efficient mechanism for transferring know-how and enabling “entrepreneurs to acquire business acumen, understand the unspoken rules of start-up challenges, and access networks of talent, knowledge, and resources.” It is also important, Demaidi points out, for the general population and for women in particular, whose participation rate (less than 19 percent) in the workforce continue to be low. Technological change has been a disruptive force in the past, and Mona Demaidi is counting on its being a disruptive force again.

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect IMF policy.