Not Flexible Enough? Recent Conduct of Exchange Rate Policy

August 3, 2023

President Hichilema, Minister, Governors, Colleagues—all protocol observed, as I have been taught to say.

It is truly a great honor to be with you all today. Even more so to be giving this Keynote Address.

For the last few years, the macroeconomic policy issue in Africa that has garnered much, much attention has been the rising level of public debt. Appropriately so, given how significant a problem it is in quite a few countries. And this naturally has led to much discussion of the conduct of fiscal policy over the years.

Denny, Governor Kalyalya, I hope you will not regret giving me this platform as I turn the focus to another policy area where significant challenges are also evident: exchange rate policy. This of course is very much in the wheelhouse of central bank governors assembled here.

Exchange rate policy is of course among the most sensitive, controversial, and animating issues that policy makers must handle. And understandably so: adjustments in no other economic variables can affect relative income and wealth for so many people as instantaneously as a large and abrupt change in the exchange rate can. The upheaval it can evoke was vividly captured by Oscar Wilde in his play The Importance of Being Earnest. Miss Prism, the tutor of Cecily, advises her to “… read her political economy” but to “omit… the chapter on the fall of the rupee… it is somewhat too sensational. Even these metallic problems have their melodramatic side.”

This morning, I will try and proceed in as balanced a way as I can. But given how emotive we all get around the issue, I am not certain that I will succeed. In any case, let me start with a few important caveats.

- First—and I want to be very clear on this point—the focus of my intervention today relates to those cases where the exchange rate regime is flexible.

- Second, given the huge heterogeneity of circumstances, institutions, policies across the region, I hope you will forgive some of the generalization that follows. In my defense (and I will try to show this with a few charts early in my remarks) the challenges I highlight are not limited to a few countries.

- Finally, there are myriad factors that constrain the quality of growth, development progress, and poverty reduction in our countries. Inappropriate calibration of monetary and exchange rate policy in some countries is an important factor, but of course by no means the only reason.

In what follows I will start by trying to explain why this is an area of concern particularly at this juncture. I will then outline the main arguments that are frequently put forward against exchange rate adjustment and offer some counter points before concluding my remarks.

I. Why focus on this now?

In the broadest of term, there are broadly four reasons why we need to consider whether the calibration of monetary and exchange rate policy over the last many years has been appropriate.

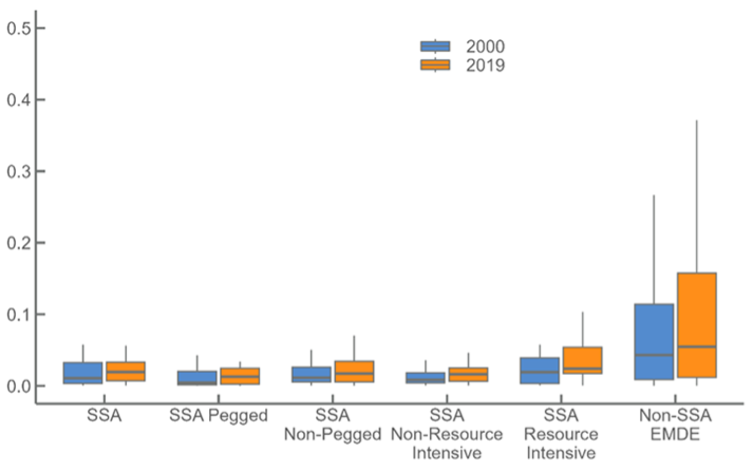

Exhibit 1. The region’s share of global exports has remained meagre, despite relatively strong growth performance and improvement in many other development indicators during the pre-COVID years—reduction in poverty, improved social, health, and educational attainment, infrastructure delivery etc. As Figure 1 shows, between 2000 and 2019, the share of SSA countries in global exports has been negligible (moving from 1.5 to 1.7 percent of total global exports).

|

Figure 1. Sub-Saharan Africa: Export Share (Percent of world exports) |

|

|

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators database. Note: SSA = sub-Saharan Africa, EMDE = Emerging Market and Developing Economies. |

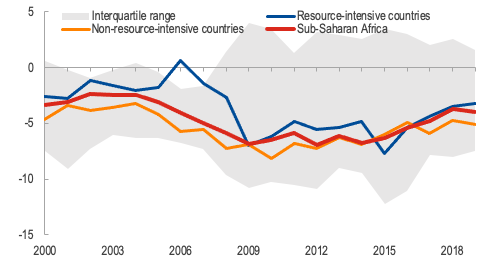

Exhibit 2. Since the turn of the century (and more so since around the end of the global financial crisis) current account deficits in the region have been persistently elevated. This has been true for both commodity exporters and countries with more diverse exports. The main cause for the elevated current account deficits I think are fiscal policy and capital inflows. But the calibration of monetary and exchange rate policy did not help either. This point needs some elaboration so let me expand on this a bit. When the global financial crisis hit, fiscal deficits in the region widened markedly for temporary demand management reasons but also to exploit the borrowing space countries had to invest in much-needed infrastructure, health, education, and the many other development priority areas. This pull factor for capital flows was supplemented by exogenous push factors. As advanced country central banks embarked on aggressive unconventional monetary easing, it evinced a search for yield that prompted large capital inflows to the region. In this context, there was some leaning against the appreciation pressures (as evidence by some reserve build-up) but much less than observed in the vast majority of other EMDEs or warranted by fundamentals.

|

|

|

||

|

|

Figure 2. Sub-Saharan Africa: Current Account Balance, 2000-19 (Median, percent of GDP) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook database. |

|

||

|

|

|

||

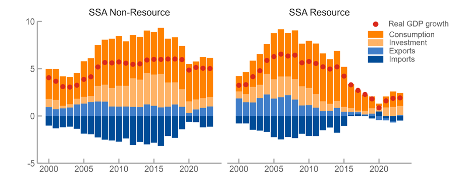

Exhibit 3. Growth is typically stronger and more sustained when it has a strong element of export orientation. To a first approximation, this is because growth that relies on tradable activities allows a country to produce and supply for a virtually limitless market; non-tradable activities are limited by the domestic market size. One, albeit indirect, way to gauge this is to decompose economic growth into the elements contributed by more inward-looking activities (consumption, investment, etc.) vs exports. The chart below clearly shows that the extent to which growth was driven by external orientation (light blue bars) in our region has been less than in other developing countries since 2000. And in more recent years still, the contribution of exports to growth, particularly for commodity exporting countries, has been markedly less.

|

Figure 3. Growth Decomposition, 2000–23 |

|

Figure 4. Growth Decomposition |

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook Database. Note: Comparators include Bangladesh, India, and Vietnam; SSA = sub-Saharan Africa; EMDEs = Emerging Market and Developing Economies. |

|

Note: Comparators include BGD, IND, and VNM. Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook Database |

||||

A legitimate question to raise at this point would be why I am not providing more direct evidence of clear exchange rate misalignment as Fund staff does quite a bit of analysis on this issue. Two reasons. First, to keep discussion tractable.[1] Second, ultimately, what matters is the outcome variables and less the intermediate variables—as they say, the proof of the pudding is in the eating.

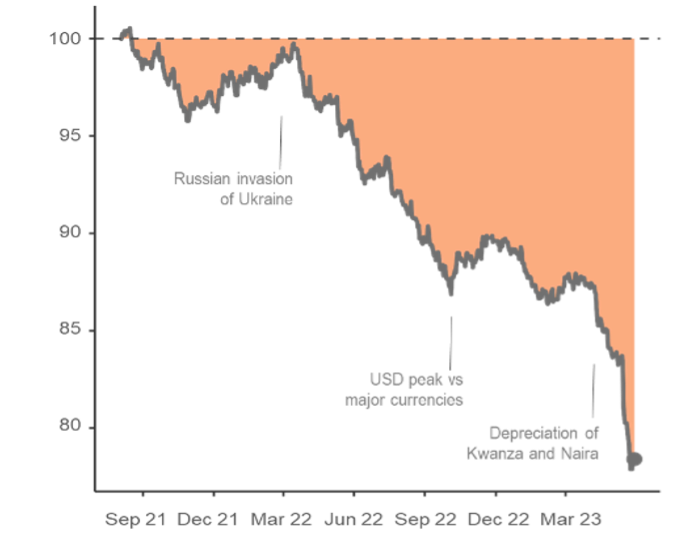

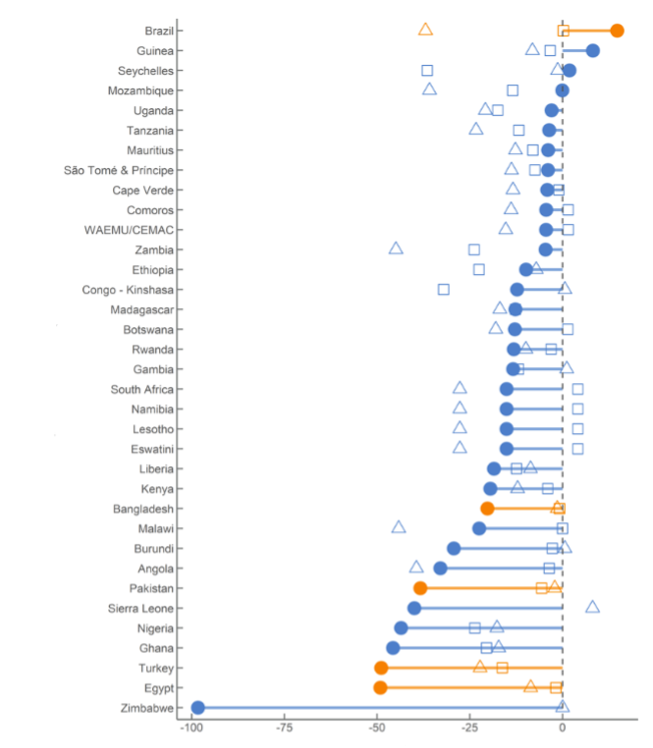

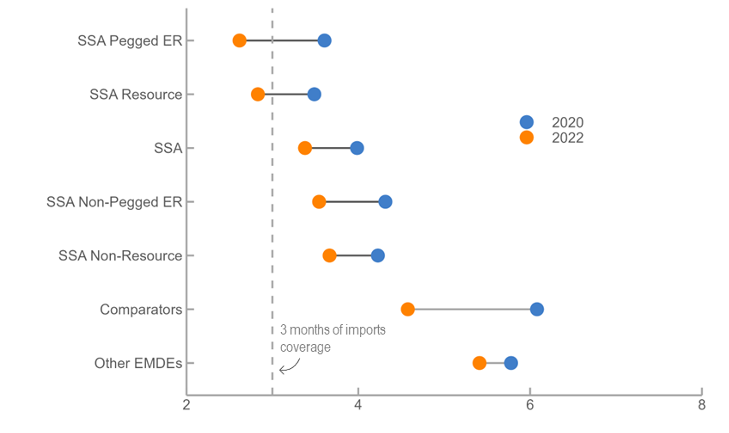

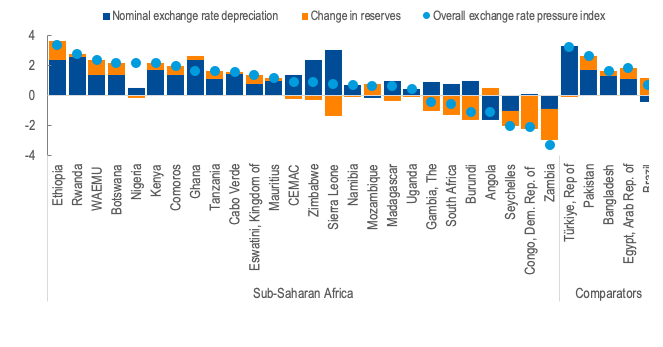

Exhibit 4. If the forgoing has not been sufficient to persuade you, perhaps more recent developments will do so. I’m here talking about the last 2 years or so, as our countries have been shut out of capital markets, cost of funding has shot up, and the terms of trade has deteriorated for the vast majority of countries. Of course, in response to this, there has been significant exchange rate depreciation in the region (Figures 4 and 5), but also clear indications that the extent of depreciation has not been sufficient. In any case, it has come at considerable cost. In particular, there has been quite a pronounced decline in foreign exchange reserve in the region—problematic of course given the level of reserves in most countries were on the low side (Figure 6). Figure 7 shows an important reason for this: central banks have for the most part responded to the pressures they faced by selling reserves and not as much by allowing exchange rate depreciation. And this chart does not fully capture the extent to which countries have sought to avert exchange rate depreciation. In some cases, a raft of administrative controls and quantitative restrictions on current and trade transactions have been introduced. Once active and liquid foreign exchange markets in a few countries have atrophied. In some other cases, parallel foreign exchange markets have re-emerged and, in the cases, where they already existed these premia have widened dramatically. Shades of the rather messy monetary and exchange rate policy arrangements that prevailed in many countries in the 1980s in our region!

|

Figure 4. Sub-Saharan Africa: Exchange Rates vs U.S. Dollar, Sep. 2021–Jun. 2023 (Sep 1, 2021=100, trade-weighted mean) |

Figure 5. Exchange Rate vs U.S. Dollar (Percent change, triangle = Global Financial Crises, square = Taper Tantrum, dots with bar = end-2021 to June 29, 2023) |

|

|

|

|

Sources: Bloomberg LP. and IMF staff calculations

|

Sources: Bloomberg LP. and IMF staff calculations

|

|

|||

|

|

II. Arguments for resisting exchange rate depreciation pressures

I don’t think there is anybody in this room that considers the outcomes I am characterizing here as optimal. Rather, in the face of the brutal exogenous shocks that our countries have faced, many of you have been caught between a rock and a hard place and had to make invidious tradeoffs. The question is whether these tradeoffs are optimal.

I suspect you all know where I come out on this. But this is not for having failed to carefully consider the challenges that significant exchange rate depreciations can engender. In this section I outline the five main arguments often made for resisting depreciation pressures and offer counter arguments.

A. “The exchange rate is the most important nominal anchor”

The exchange rate in most developing countries is the most visible and important price in the economy and so helps to anchor expectations, facilitate planning, as well as investment, and consumption decisions. This is partly by design and partly for lack of an alternative—I look forward to the discussion later today on the pros and cons of alternative nominal anchors for monetary policy. Within a certain range of exchange rate movement, economic agents can tolerate and refine their decisions. But when it moves significantly and precipitously it can be highly disruptive. And for this reason, significant exchange rate fluctuations tend to be resisted.

These are very valid points and an important a reminder that policy making is very much about making difficult trade-offs, particularly when there is so much uncertainty whether the shocks that are hitting economies will endure or reverse. So let me offer a few counter arguments:

- As noted above reserves have slipped in many cases to uncomfortably low levels. Persisting with foreign exchange interventions risks depleting reserves and delaying the inevitable by only a matter of, say, a few months. After that, reserves will have been exhausted, the exchange rate adjustment will still take place, leaving the country much more vulnerable to higher still exchange rate volatility and the inability to cushion future shocks.

- Alternatively, a country could tighten monetary and fiscal policies aggressively to offset depreciation pressures. But it is not clear that undertaking additional fiscal tightening on top of what countries are already planning and finding challenging to achieve is feasible or desirable.

- The use of quantitative restrictions—bans of certain imports, limits on access to foreign exchange, etc—is something that has unfortunately remerged in some countries. As I noted above, these approaches used to be all too common in our region in the 1980s and early 1990s. Their effect was to greatly undermine investment and growth. They led scarce resources to being allocated in the most untransparent and inefficient way possible. And that was when economies were relatively more simple. Quite futile to try administrative allocation in the context of the incredible complexity that is evident in our economies these days.

B. “Depreciations exacerbate inflationary pressures”

By raising the price of imported goods, exchange rate depreciation of course quickly has a bearing on domestic prices. Most countries are fuel importers and a fair number also are significant food importers. And when there is a confluence of factors at work as in recent months—sharp increases in commodity prices, higher global inflation, plus a significant tightening of global financial conditions—the extent of pass through to domestic prices is likely to be quite important. And not surprising, inflation in the region has surged to levels last observed in the 1990s.

My counter point to this is that extent of “pass through” of exchange rate depreciation to domestic prices generally depends on overall monetary and fiscal conditions. So even in instances where a country has a healthy level of foreign reserves and could sustain intervention for a while, its effectiveness in limiting inflationary pass through is contingent on monetary and fiscal conditions calibrated well enough to support this endeavor. So it is the overall macro policy setting, particularly the monetary policy setting and its credibility, rather than exchange rate change that often has the stronger bearing on the pass-through.

C. “Depreciations are contractionary”

Another concern often invoked is the fact that devaluations can have a contractionary effect on economic activity. By raising the price of imported goods, they can reduce investment and consumption appetite and, indeed, curtail production in some important sectors. Imports are of course a compliment rather than a substitute in the production process. Thus, when their prices go up, it can cause firms to curtail their output.

A variant of this argument draws on the experience of many African countries from the 1980s. There was much depreciation back then for many of the same reasons—to respond to adverse terms of trade shocks, preserve scarce foreign exchange reserves, boost exports, etc. But despite significant depreciations, exports did not increase much because (i) the export sector is rather small to provide important growth impetus and (ii) structural, often physical, impediments to trade remained unaddressed. In this context, it required large depreciation to engender the desired outcomes.

Again, there is much truth in these arguments.[2] But it is also important to consider their full implications.

Depreciation pressure seldom occur in countries with current account surpluses—and when it does, it is often transitory. Such pressure instead is generally present when there is a current account deficit, and this is the norm in our region. If a country does not want to let its exchange rate adjust in order to limit its current account deficit in the face of adverse shocks, then it requires increased capital flows (usually through external borrowing) to sustain the higher deficit. This is problematic, for one, external finance often is highly pro-cyclical and generally disappears exactly when countries are facing adverse supply shocks—as we have seen all too well recently! Second, even assuming such borrowing is readily available, it is going to have to be repaid sometime down the road. Sooner or later, significant internal rebalancing is going to be needed to facilitate transfers abroad. Third, there is in fact much empirical evidence pointing to the fact that undervaluing one’s exchange rate is more helpful for sustaining growth. [3] The argument to resist depreciations because they are contractionary flies in the face of that. Fourth, it is also important to consider the asymmetric effect that exchange rate misalignment often has. For example, we focus on the disruptions that depreciations can have on certain existing activities because they are observable and measurable. But the activities that have been prevented due to exchange rate overvaluation remain unaccounted for. This is often one of the most difficult aspects of making the case for reforms—the groups that stand to lose out are legion and vocal, the groups that stand to benefit yet to emerge.

D. “Depreciations have large adverse balance sheet effects”

The previous two arguments against depreciation focus on the effect that it can have via current transactions. But the valuation effects that exchange rate adjustments have on external liabilities is also an argument often invoked. Significant devaluation increases the local currency value of external obligations proportionately. For corporates, households, and indeed the public sector—whose income stream is mainly local currency denominated—this can markedly increase the level of debt and the servicing burden markedly. In cases where the financial sector, in particular, has a significant open foreign exchange position, the situation can be even more dangerous. There are many cases globally where a devaluation has precipitated an acute financial crisis that has engulfed the rest of the economy—Mexico in 1994, Thailand in 1997, Indonesia in 1997 are all prime examples.

In most countries, the main channel through which this is likely to cause difficulty is via its impact on the public sector balance sheet. Take the case of a country where the debt sustainability situation is borderline and an exchange rate depreciation would markedly aggravate the situation. The country might be forced to seek debt rescheduling or even restructuring—an irreversible, protracted, and difficult process. And given the tendency for exchange rate pressures to ebb and flow, it could very well be that in a matter of months the exchange rate reverts to earlier levels. I am drawing here on the recent experience of a couple of countries in the region.

My counter argument is that exchange rate depreciation is very rarely the “straw that breaks the camel’s back” (tipping debt into a clearly unsustainable situation). All too often the main driver of public debt problems are many years of high fiscal deficits, generally coupled with an overvalued exchange rate. The depreciation when it comes is evidence of these factors coming home to roost. Still, it is important that debt sustainability assessments, being the forward-looking and forecast- driven exercises that they are, pay heed to the uncertainty around the path of key economic variables. Wherever this has been accounted for and the analysis shows debt sustainability to be an issue, restructuring needs to be pursued. So again, delaying exchange rate depreciation to try and mask a public debt problem is delaying the inevitable at the expense of growth and much else.

One other point related to balance sheet vulnerabilities that I heard our good friend Governor Lesetja Kganyago make recently:[4] Central banks, whose liabilities are mostly in local currency, experience positive valuation effects on foreign exchange reserves during currency depreciation. This accumulation of reserves serves as a hedge against the public sector's FX debt.

E. “Depreciations cause social and political upheaval”

I went back and forth whether I should include some discussion of this issue. Ultimately, I felt it necessary given how significant a bearing political economy considerations have on exchange rate policies and vice versa. I have already touched some elements of this—as to how a significant exchange rate adjustment promptly affects the relative income and wealth for a broad swath of the population and also the important role, as the single most visible price in most economies, the exchange rate plays in anchoring expectations and economic decision making. Another feature of the exchange rate is the extent it is used as the barometer of national economic wellbeing. And this is not unique to our countries but also well beyond. The stronger the exchange rate is, the better an economy is considered to be doing; the weaker it is, the more poorly an economy is considered to be doing[5]. It is often a matter of national pride! Thus, exchange rate adjustment, beyond its economic consequence, also has huge political significance.

A couple of thoughts on this minefield of a topic:

- Exactly because of the distributional consequences that exchange rate policy change has, it is very important to communicate the balance of considerations that is informing decision making. Important to show here short-term costs have to be weighed against the higher still costs of maintaining an overvalued exchange rate. Show how the interest of more import-dependent and vocal groups, need to be weighed against those economic activities that are being stifled because of misaligned exchange rates. Show how resisting depreciations for political reasons is a classic case of short-term expediency dominating the longer-term and broader economic interests of the country.

- Second, we need to make the case for concrete steps that can be taken to mitigate the adverse effects depreciation can have on the poorest and most vulnerable households in particular—for example, by increasing transfers in the immediate aftermath of large depreciations.

III. Concluding Thoughts

I have gone on for rather long so time for me to end my intervention, with two final points.

First, I hope that my remarks, where I have tried to devote more time to the arguments against exchange rate depreciation than the case for depreciation, if nothing else shows that we do listen, hear your concerns, and learn from the many hours of discussions we have with you.

Second, my colleagues and I are also fully conscious of how difficult the last few years have been. Even in the best of times, policy making in our countries is an extraordinarily difficult task. Our admiration for the work that you do, the difficult trade-offs that you have to make almost daily is boundless—compared to the constraints you face, policymaking in the so-called advanced economies is a breeze. All the same, there are some policy choices that are important to avoid. And that is how I think about the efforts to resist depreciation pressures even when depreciation is clearly warranted and the cost of avoiding it so high. It reminds me of a saying we have in my country: for fear of a dog bite, better to not run towards the hyena.

In all, this is a call for pragmatism and learning from both our own experience and that of others, less so an appeal to ideology or theory.

Thank you again Denny, and the Association for your generous invitation to address you today and your kind attention this morning.

[1] An overview of recent Fund assessments of exchange rate misalignment in the region is provided by IMF, 2022, The Role of Foreign Exchange Intervention in Sub-Saharan Africa’s Policy Toolkit, Analytical Note, Regional Economic Outlook – Sub-Saharan Africa, April 2022.

[2] Yet another argument for exchange rate depreciation having a muted effect in stimulating exports is the prevalence of dollar invoicing. But while a large share of exports is indeed invoiced in dollar in resource-intensive sub-Saharan African countries, this is much less true for non-resource intensive countries in the region, even compared with emerging markets and developing countries outside the region.

[3] There is much important work by the likes of Professor Dani Rodrik showing that an undervalued real exchange rate can help boost export growth, with the undervaluation serving to offset the structural and institutional constraints that raise the transaction costs for exporters. A big fan as I am of export-led growth, I think that avoiding overvaluation would be an important goal in the first instance.

[4] Kganyago, L., 2023, The contribution of capital flows to sustainable growth in emerging markets, 2023 Michel Camdessus Central Banking Lecture by Lesetja Kganyago, Governor of the South African Reserve Bank, at the International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC, 11 July 2023

[5] An exception here are some highly export-oriented East Asian economies where exchange rate appreciation is overall economically and politically unpopular.

IMF Communications Department

MEDIA RELATIONS

PRESS OFFICER: Nicolas Mombrial

Phone: +1 202 623-7100Email: MEDIA@IMF.org