Transcript of a Press Conference on European Outlook by Marek Belka, Director of the IMF's European Department with Ajai Chopra, Deputy Director of the European Department, and Anne-Marie Gulde-Wold, Senior Advisor in the European Department

April 24, 2009

Washington, D.C., April 24, 2009

MS. GAVIRIA: Good day, everyone. I am Angela Gaviria, of the External Relations Department. Welcome to this briefing on the economic situation in Europe and the role of the IMF.

Let me introduce the speakers now. At the center, we have Marek Belka, Director of the IMF's European Department. To his right is Anne-Marie Gulde-Wolf, Senior Advisor in the European Department. And, to my right is Ajai Chopra, Deputy Director of the European Department.

Marek Belka will make some opening remarks. He will also have slides to accompany the remarks. And then, we'll open the floor to questions. Marek.

MR. BELKA: Thank you.

Good morning, ladies and gentlemen, and good afternoon for those in Europe.

In my remarks, I will first give you an overview of the economic situation in the advanced countries of Europe and then turn to emerging Europe.

Europe is in deep recession. The downturn was triggered by a global financial crisis and a sharp drop in trade. The twin nature of the shock is particularly painful for Europe because of its deep integration in the world economy. Following the rapid expansion of its trade in recent years, exporters have been hard hit by the sharp drop of global spending on capital goods and durables.

Advanced Europe also has its share of homegrown problems. In some economies, such as Spain and Ireland, real estate busts are worsening the recession, as households and firms cut back demand and banks react to the rapid deterioration of their credit and asset portfolios by curbing lending. Similarly, some European banks were as guilty of high leveraging and use of adventurous funding models as U.S. financial institutions.

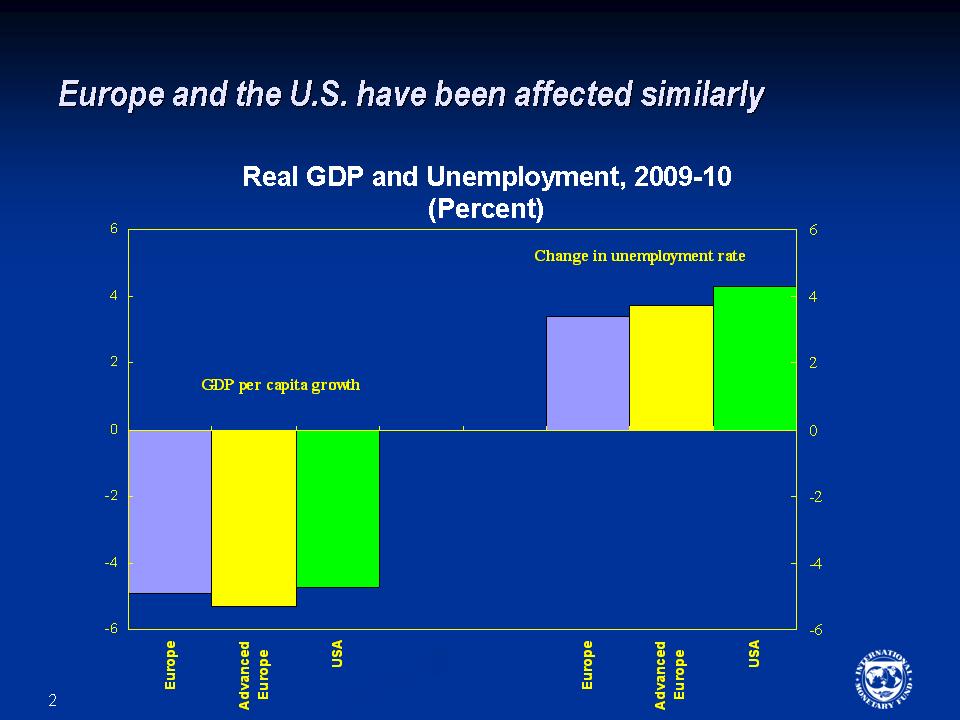

Having said this, I would like to point out, however, that contrary to the perception of some, the fall in output in the advanced European economies in 2009 and 2010 is expected to be only slightly worse than in the U.S. when output is measured on a per capita basis.

And, if you look at the slide, you can see that the change in unemployment, to the worse, unfortunately, is smaller in Europe than in the U.S.

It is clear today that the financial sector is at the heart of Europe's problems, but also holds the key to recovery. While progress has been made, Europe still needs to act more forcefully to restore financial confidence. This requires recognizing losses in a forward-looking way, further recapitalization and address difficult-to-value impaired assets. This to-do list is not specific to Europe. What is specifically European, however, is that getting the financial sector in order will require effective cooperation between the various governments and authorities.

Finally, is Europe doing enough in terms of macroeconomic policy? In our view, the ECB still has some room for monetary easing, and we believe they will make use of it in a timely manner. And, fiscal policy, including through automatic stabilizers, has moved to support the economy this year and next year. Overall, we are confident that macroeconomic policies will help Europe to soften the downturn. But let me repeat that for the actions of the monetary and fiscal policymakers to be fully effective, Europe needs to move rapidly to iron out its financial sector problems.

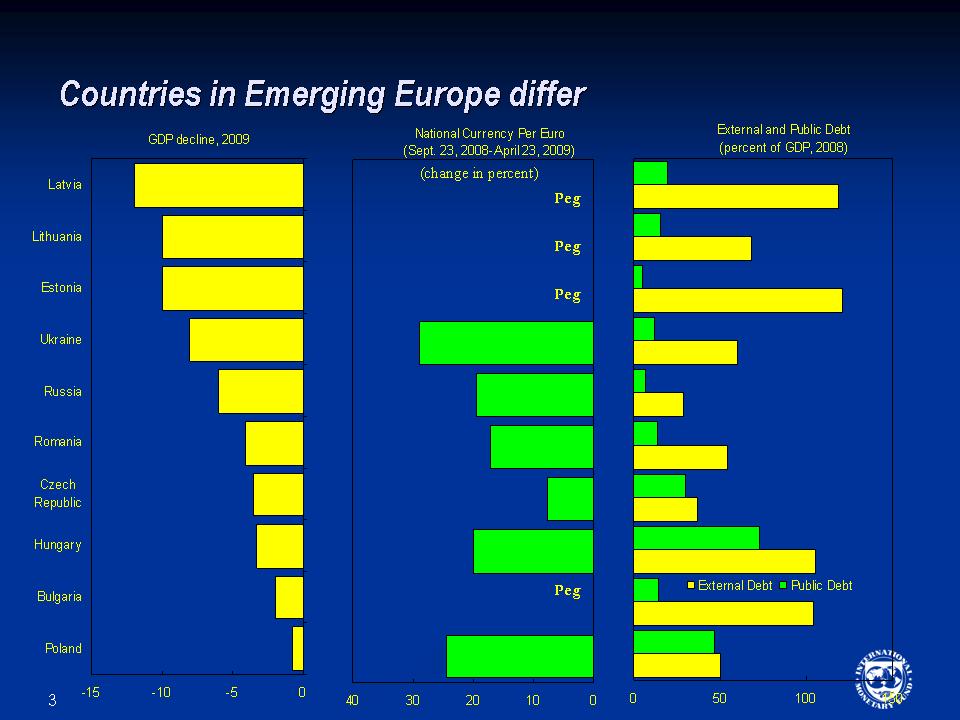

Now let's turn to emerging Europe. It has been hit hard as well. The severity of the crisis differs between countries, however, reflecting initial conditions.

Look at the slide: debt levels, both external and fiscal, and policy frameworks, fixed or flexible exchange rates. By and large, the region has been affected through two channels:

First, exports have plummeted, given the region's high degree of integration into global trade and their heavy reliance on manufactured goods including consumer durables like autos and electronics. In some countries, industrial production in the beginning of the year has fallen by more than 30 percent. For floating exchange rate countries, the low level of global demand has severely limited the supply response to the currency depreciations in the region.

Second, countries in the region also face significant financial sector challenges. Much of Eastern Europe's recent rapid growth has been financed by capital inflows to the private sector. Economic downturn and, in some countries, depreciating currencies are bound to lead to increases in non-performing loans, including danger to the soundness of financial sectors.

Stabilizing financial sectors in Eastern Europe will require joint action by home and host countries of banking groups active in the region. There is a collective action problem because parent banks are often based in different West European countries. These banks have made significant investments but will only stay engaged if they are assured that other banks will not benefit by leaving early.

The Fund, in cooperation with other IFIs is therefore working toward agreed principles of home and host country responsibilities for recapitalization. In the case of Fund programs, we seek formal agreements on rollover rates for credit and on the shared responsibility for maintaining adequate capital levels.

The outlook remains difficult, but the Fund stands ready to help. Some countries may see a further delay of expected return of positive growth. Others, especially those which started out with more sound domestic policies, have so far been more resilient but are at risk from a possible fallout of a deepening global recession.

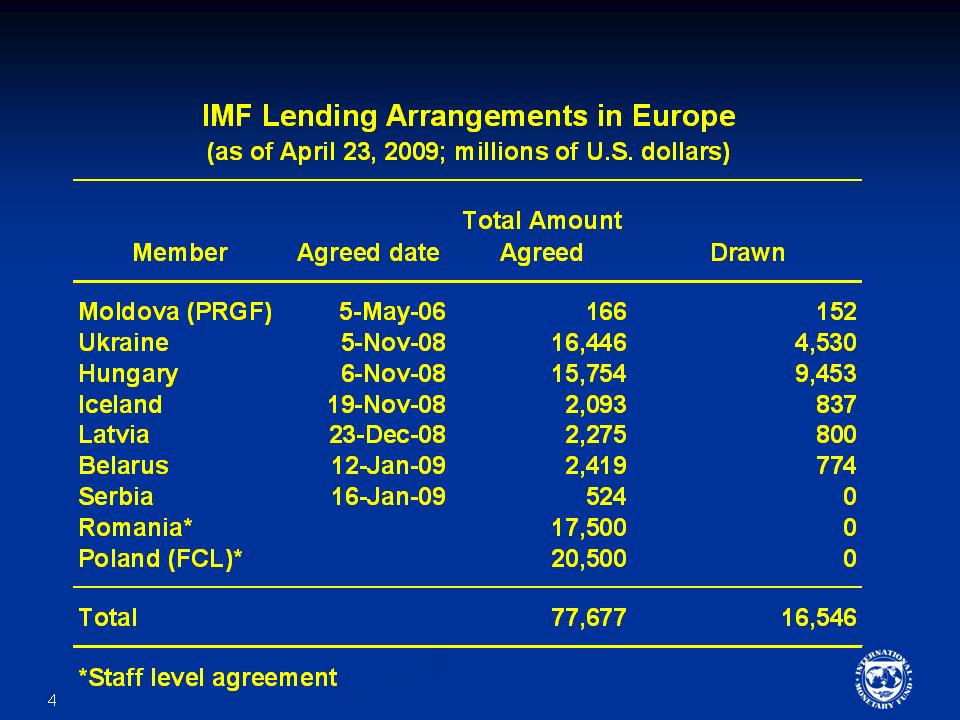

The Fund has differentiated its support accordingly. You see the slide. We are lending to those most hit by the crisis. We are providing insurance to good performers who are innocent bystanders but may nevertheless be affected, and, here, the case is Poland.

Some countries may not need our financial support at all but nevertheless appreciate our policy advice.

Whatever the circumstances, the Fund remains very much engaged in the region in close cooperation with the E.U. and other multilateral partners.

Well, thank you very much for your attention. Excuse me for my voice, but you know this is a function of the severity of the crisis and the number of programs that we have.

QUESTIONER: I'm sorry, I'm going to ask about a country already, not the global view of Europe, but my country, Spain. The Managing Director yesterday mentioned concern about the rising spreads in Spain and other countries, and I was wondering if there is a fear there in the Fund that if the Spanish government takes new stimulus measures, makes more commitments to the economy, those spreads will increase.

And, a second one, if I may. In the report about Spain that was released this week it is said that the fiscal situation is not sustainable in the medium term, that Spain has to do something, and I wonder if you could tell us a bit of what that something is. I mean what kind of reforms the country has to take right now to put their finances in order.

MR. BELKA: Ajai, will you take up this one?

MR. CHOPRA: Yes. I think I'll take up the first one. The second one is a very specific question that I think is better left to the Spain team, and I think they had a fairly comprehensive press conference recently.

Firstly, in our view, the Spanish government has already taken sizeable fiscal measures to date. The measures that they've taken over the last couple of years add up to 4 percent of GDP. This is in 2008, 2009. And, on top of that, we have to remember that the effects of automatic stabilizers are quite large in a country like Spain. So, taken together, there's been a swing in the fiscal balance of about 10 percent of GDP in 2 years, and debt is increasing quite quickly.

So, in our view, this is enough for now. I think the new finance minister has also said that great care needs to be taken in the design of fiscal policy, and I think the important point is that a lot has been done. To the extent that there is any more stimulus or any further expansionary measures, these need to be linked very closely with addressing the structural problems that the economy faces, both in labor markets, product markets and so on.

QUESTIONER: You mentioned that if you have depreciating currencies, you have more non-performing loans. But what about the Baltic states? That's my focus with this question. They have currency pegs, and yet they've got considerable problems in their financial sector, which is largely controlled from outside the country. Is the choice for the Baltic countries essentially between the severe deflation that they're experiencing and devaluation?

And, I'm just wondering, with Mr. Rimsevics of Latvia here this week and the report that some in the Fund produced about coming into the euro zone early, if you could comment about the economic situation in the Baltic states and whether this severe downturn that they've experienced was a choice they made and, if so, if that choice is sustainable or if, in the end, they'll have to devalue anyway.

MR. BELKA: Well, the easiest thing, the easiest part of your question is about whether it was a choice made by them, and the answer is an emphatic yes. It was a choice that they made early in the '90s. This was a main pillar of building up stability of their economies, a regime that proved to be both resilient and successful for these economies, and they are still, without any reservation, supporting this regime.

There are strains, of course. The imbalances have built up in the past. Now these imbalances are being unwound, and the question is what exchange rate regime is most helpful to unwind these imbalances.

There is no good solution in such a situation. Whatever you do, you have to go through a painful adjustment process.

What is very important is to have an exit strategy, and, for these countries, a clear exit strategy is accession to the European monetary union.

How clear the way is, how realistic the way to fulfill the Maastricht criteria in the current situation, they stick to this. They do what is necessary, even if very painful. And, we hope that they arrive at a moment when the European institutions will deem it acceptable for them to join the European monetary union. This is the positive scenario that they stick to, that we are basing our current program in Latvia on.

Thank you.

QUESTIONER: My first question concerns Poland. The deputy minister of the treasury told that they won't use any of the flexible credit lines. I don't want you to comment on this sentence, but I wish to know: Do you see any chances for Poland, the Czech Republic, or Hungary to finance their debt on the market? The second question concerns Hungary. The Hungarian Stand-By Arrangement expires in March 2010. Do you think there is any bridge between a Stand-By Arrangement and the flexible credit lines? Can some countries change the previous to the next one?

MR. BELKA: Well, one of the main goals of our programs in the countries that you mentioned, especially Hungary ―Poland, the Czech Republic do not have programs― is to stabilize the financial standing, the confidence around the countries and rebuild their possibility to finance themselves on the international capital markets.

Poland and the Czech Republic are not shut out of the international capital markets so far, and we do not see a danger. On the contrary, there is a strengthening sentiment in this respect as of recently.

Well, Hungary is in a more difficult situation, but we greet the positive developments in the internal markets. Long-term papers, namely the five-year treasury bonds, have been successfully issued, I guess, yesterday. And, this is a sign that, again, sentiment on the capital markets around Hungary is improving. So this is one of the signs that the program works.

Well, the program in Hungary is basically on track. We are prepared to negotiate how this program will be continued. We do not exclude a situation in which the program could be lengthened if necessary.

There is no clear or automatic link between an SBA and the FCL. There is no automatic switch to it. FCL is meant for countries that have strong fundamentals and a good policy record. And, as you know, the countries that have applied, that have requested an FCL are members that can easily be characterized as having strong policies and strong records.

I hope that one day Hungary will either qualify or will not even need this because the situation will improve so much that we'll forget about the need of an FCL.

MS. GAVIRIA: I'm going to take one question that has arrived online. This is a question coming from Austria: How strong will Austria be hit by the problems that are facing Central and Eastern Europe?

MR. BELKA: Obviously, Austria is part of Europe, Western Europe, part of euro area, and is not immune to the shocks and to the problems that are characteristic, common for the whole area. What is specific in Austria is this country's considerable exposure to Eastern Europe. I would suggest that Anne-Marie Gulde elaborates on this.

MS. GULDE-WOLF: Yes. As most of you know, Austria has a very high exposure to Eastern European banks. It's about 70 percent of its GDP. So, clearly, the developments in Eastern European countries will affect the profitability and the capitalization of Austrian banks.

So far, we have seen a decisive response from the Austrian authorities. Austrian banks have been recapitalized at home with an ability also to recapitalize the subsidiaries in those countries, and this has helped stabilize and minimize the effect that we see in the Eastern European countries.

So, obviously, going forward, the question will be how deep the crisis will be in Eastern Europe. We have given you some views on that. We have seen that if, for example, non-performing loans were to rise in some countries up to, say, about 10 percent of total loans given, that this would still be able to be managed by most of the Austrian subsidiaries. But it would really impact the level of profits. It's important to notice that about half of the profits of Austrian banks have been coming from the East.

So, in terms of whether this will be a sustainable situation, the question is how long the situation will last and how deep the recession will be in Eastern Europe.

It also bears and, as Mr. Belka said at the outset, that not all countries in Eastern Europe are affected in the same manner. We have done some stress tests, and we have seen that Austrian banks could survive relatively easily if there are problems in one or two banks. But if we would see a much deeper problem in the region and we would see many countries hit at the same time, this would really change the situation.

QUESTIONER: A question for Mr. Belka: After yesterday's PMI data on Europe, do you share the opinion of many economists that we are seeing the bottom of the crisis in Europe and there are green shoots of a recovery in sight or not?

And, a second question about toxic assets: Do you think the euro zone is doing enough and moving quickly enough to deal with toxic assets or should it do more and faster?

MR. BELKA: Well, as to the so-called green shoots, I think we are all hopeful that this is really the beginning of a changing situation.

We are very careful, very cautious about describing it as a turning point, and we reiterate our view that we see a chance, a good chance of the economy picking up in the first half of 2010. This is contingent on good policies, on continuation of the current stance in monetary and fiscal policies.

And, let me reiterate it with all the force. It all depends on how efficiently we'll deal with the financial sector, how efficient we clean our banks. Nothing will work properly and fast enough without it.

MR. CHOPRA: On your question about toxic assets, the GFSR that was released just a couple of days ago did highlight that there is still a substantial amount of likely impaired assets when we look forward, taking into account the slowdown in the economies. This is, as Mr. Belka said in his opening remarks, not just a European phenomenon. It's happening in a number of advanced countries.

So, yes, we do feel that more needs to be done in terms of loss recognition. I think we also need to recognize that the countries have taken actions to stabilize their financial systems. There have been a variety of schemes including guarantee schemes, bank recapitalization schemes, and these have been very important. But we do think that more needs to be done, and this needs to be done in a cooperative framework.

And, what we have been emphasizing is that, going beyond this crisis, Europe needs to go about establishing its crisis resolution framework in terms of dealing with distress in banking systems.

I think there are a number of very good recommendations in the Jacques de Larosière report, and I think this would considerably improve Europe's financial stability framework. But we've also been saying that Europe needs to go beyond the de Larosière framework, and, here I think there's further improvements that need to be done in the area of regulation and supervision of systemically important institutions, especially those that operate across borders and also, as I said, crisis resolution and burden sharing.

QUESTIONER: The G20 summit met and made reference to the exit strategy you mentioned. How do you see it in fiscal terms and monetary terms in the euro area? Will the requirements of the Stability and Growth Pact be adequate?

And, what about the different monetary instruments used by the ECB when compared with the Fed and the Bank of England?

MR. BELKA: Obviously, we need active fiscal policies. We preach fiscal stimulus, but at the same time we hasten to add, and we do it in Europe also, to mind the long-term fiscal sustainability.

And, our advice is to strengthen the fiscal framework. Strengthen the Stability and Growth Pact, maybe through strengthening the role of medium-term objectives that are not attached very clearly to the pact, not attached clearly to the excessive deficit procedures.

But, obviously, a lot of thinking is needed in Europe, in the European institutions, and maybe here in the IMF to go beyond it, to strengthen the fiscal framework so that fiscal sustainability in the longer term is sustained, is kept.

As to the monetary, well, financial systems in the U.S. and Europe are slightly different, so it's understandable that the instruments used by ECB and by Fed are also different.

We have full recognition of the determination and strength of monetary policies of the ECB. I have mentioned that there is still some scope of monetary easing in terms of interest rates. We acknowledge the strong policies in terms of credit easing as it is put in by the ECB, but we also acknowledge that the two institutions should have the reason to differ slightly in their accent because of the different structure of financial systems both in Europe and the U.S.

MS. GAVIRIA: I'm going to take one online question. The question is: Germany is Europe's largest economy, but it is also heavily dependent on exports. To what extent can Germany fuel the recovery of the rest of the continent?

MR. BELKA: This is a question that can be also reversed. How can the continent rely on the recovery in Germany?

Germany is such an important part of the European economy that the fortunes and misfortunes of the economic situation of the whole Europe is deeply linked with the German situation. Of course, because of trade situation, because of, literally, trade implosion in the last month of 2008, the German economy was hit especially hard.

What is very important is that consumption, internal consumption in Germany seems to hold up quite nicely, and this is very much dependent on the situation on the labor market. That is why in my opinion it's very important that the measures taken by Germany, and not only by Germany, but other European countries, are geared towards maintaining a high level of employment because this keeps the consumer's confidence up. And, this gives hope to bridge, to weather the crisis in a better shape and start reviving a better situation.

QUESTIONER: I want to return to the toxic assets issue. Both you and Mr. Strauss-Kahn yesterday emphasized that there will be no recovery, that the recovery will be postponed as long as the problem of dealing with the financial sector is postponed. And, he said yesterday that one of the problems is a political challenge, that it's hard for governments to take action in this area because of political issues.

I wonder if you could elaborate a little more on what are the political problems that are blocking governments from taking action and cleansing their banking sectors, and be as specific as you can about what is it that these governments need to do and have not yet done.

MR. BELKA: Let me limit my comments to the following: It's for the governments to determine what measures conform with the political situation, with the traditions which we should not ignore.

Our point is the following: Be pragmatic. Don't stick to, let's say, strict ideological positions. Do what has a chance to prove efficient. State involvement should not be treated as a panacea, but at the same time, if necessary, should be tolerated at least. So, as much pragmatism, as much conformity with the values, traditions and economic situation in the countries.

MR. CHOPRA: I would just add a couple of points to that. I think we also have to remember that all these countries are facing major fiscal strains that are coming not just from the financial sector but also because of the situation in the economy and the collapse in revenues. And also, in some countries, they have been relying on revenues from the financial sector and from asset booms in housing and so on.

So, in terms of this pragmatism and to be specific, our basic prescription is that countries need to be proactive in getting the banks to recognize these losses and then be proactive in recapitalizing these banks so that they can get on with the business of lending.

But this recognition of losses can come back to the governments' books. And, then, there are different ways of handling this, as I said. Given the strains on public finances, some countries have opted to guarantee these bad assets because this may sort of stretch out when they need to bring these losses into the public accounts. And, maybe in that way, they don't require fire sales and maybe the recoveries are better when conditions get better.

There's other options, such as establishing a bad bank approach. Now, that requires more up-front money, but it may get the assets off the books of these banks so that the banks can then concentrate on the good stuff and start lending again.

And, these are the tensions that governments are facing. The tensions come back also to the fiscal accounts. But the basic point is that countries need to be proactive in loss recognition and proactive in recapitalizing the banks, be it from private sources or from public sources.

MS. GAVIRIA: Thank you, Ajai. With this last answer, we end our press conference. Thank you very much for participating.

IMF EXTERNAL RELATIONS DEPARTMENT

| Public Affairs | Media Relations | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-mail: | publicaffairs@imf.org | E-mail: | media@imf.org | |

| Fax: | 202-623-6220 | Phone: | 202-623-7100 | |