Outlook for the World Economy and Policy challenges Ahead: A Multi-speed Recovery, Keynote Address by Murilo Portugal, First Deputy Managing Director, International Monetary Fund, at the Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics (ABARE), Outlook 2010 Conference, Canberra

March 2, 2010

Keynote Address by Murilo Portugal, First Deputy Managing Director, International Monetary Fund

At the Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics (ABARE)

Outlook 2010 Conference

Canberra, March 2, 2010

As Prepared for Delivery

Good morning ladies and gentlemen. I am delighted to be with you in Canberra today. I have the privilege to visit Australia for the first time. I wish to thank the Australian government, in particular ABARE, for inviting me to share my views on the global outlook, addressing such an eminent audience. For us at the Fund, it is extremely important to visit our member countries, and exchange views on challenges we all face and to learn from successful experiences, such as Australia.

In my remarks today, I will touch on two topics. First, I will talk about the global and regional outlook. And, second I will spell out what we view as the main policy challenges.

I. Global Outlook

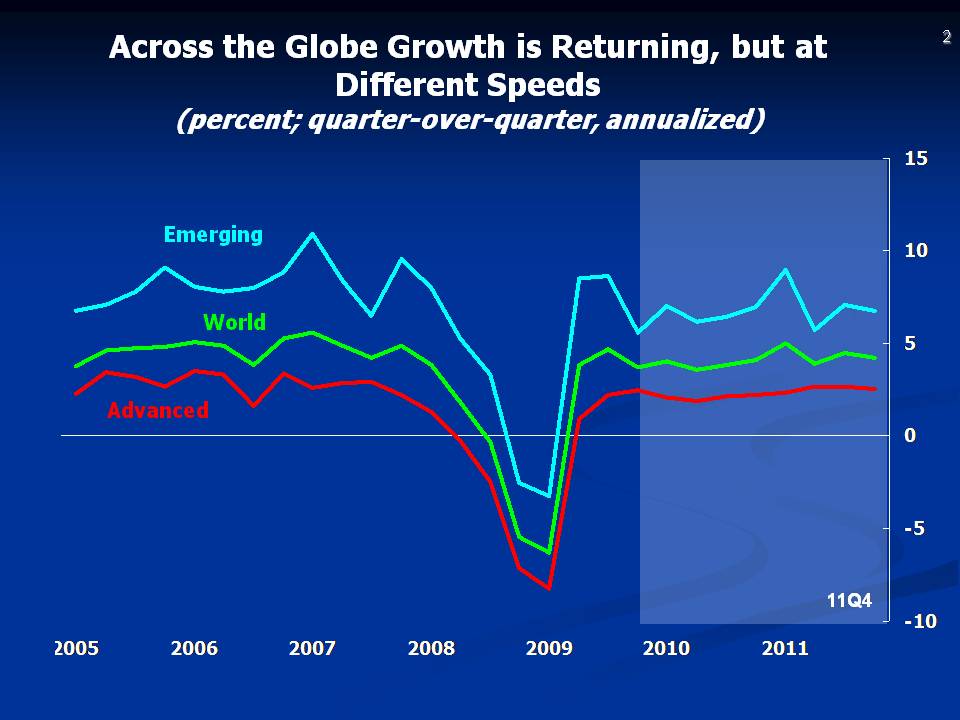

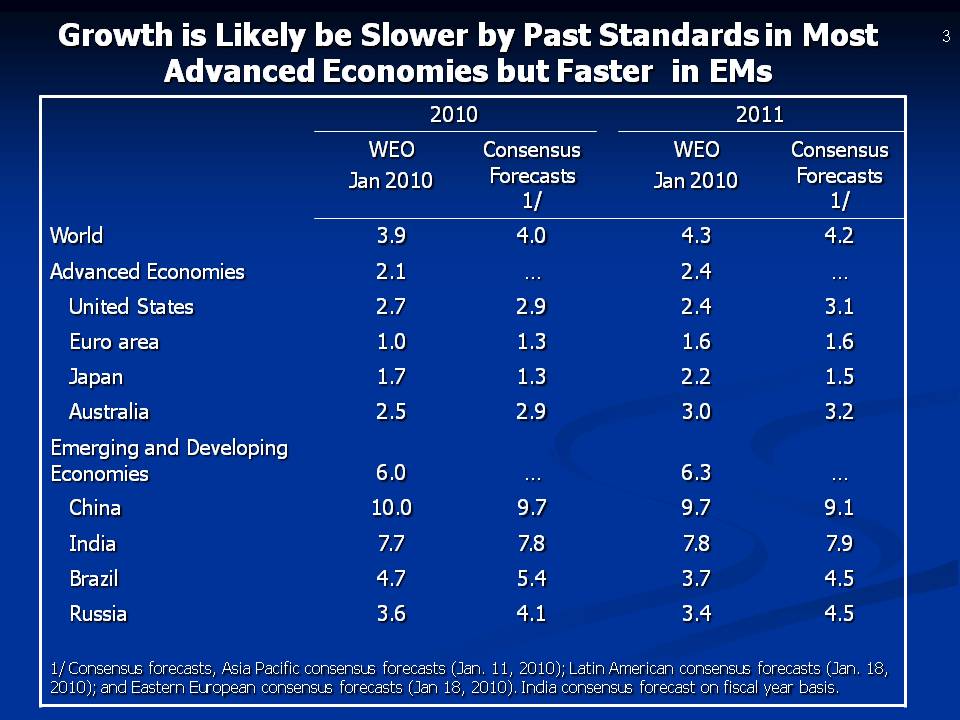

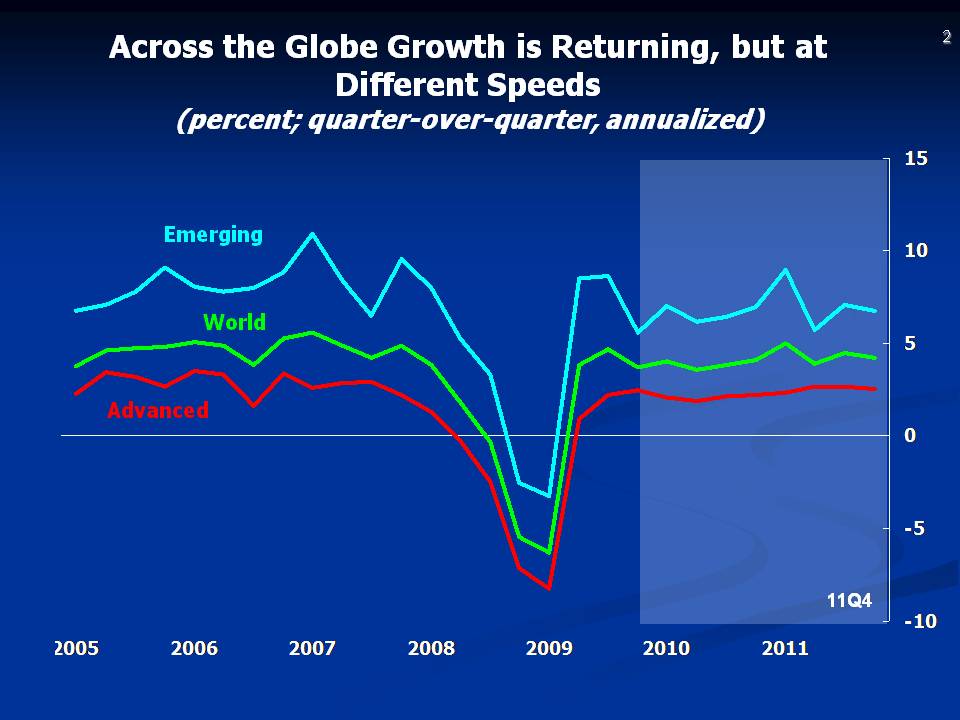

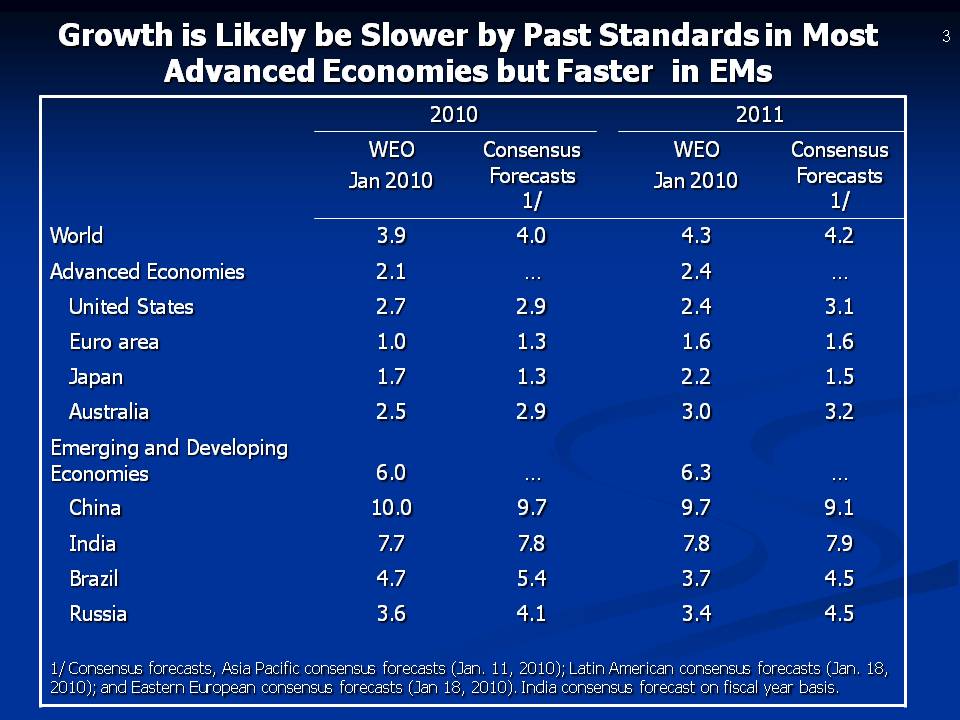

Let me start with the big picture. Following a deep global recession, the recovery is off to a stronger start than we had earlier anticipated. We recently revised up our projections and now expect global growth in 2010 to rise to close to 4 percent, with Asia leading the way. This represents an upward revision of ¾ percentage point from our October projection. This is the good news.

However, let me emphasize that the recovery is proceeding at different speeds across the various regions of the world. And it remains fragile. We moved from a remarkably synchronized global downturn to a multi-speed recovery. And this poses its own challenges.

In most advanced economies, growth is likely to be sluggish, and still dependent on government support. Output is forecast to expand on average by 2 percent in 2010 and 2½ percent in 2011 in advanced countries. The recovery will be slow by past standards. There are few signs that private demand is self-sustaining on the back of high unemployment—especially in Europe and the US. High public debt in some advanced countries, as well as still fragile financial systems, pose further challenges to the recovery.

The situation is better in emerging markets, where growth is expected to reach 6 percent in 2010. The recovery is being led by key emerging Asian economies, notably China, India, Indonesia, and Korea, largely driven by buoyant domestic demand and supported by stimulus measures. Stronger public and private balance sheets than at the onset of the Asian crisis and forceful policy responses supported activity in Asia. In China large stimulus sustained domestic demand, with positive spillovers to other economies. Commodity exporters are also recovering. But emerging markets in Europe are lagging behind.

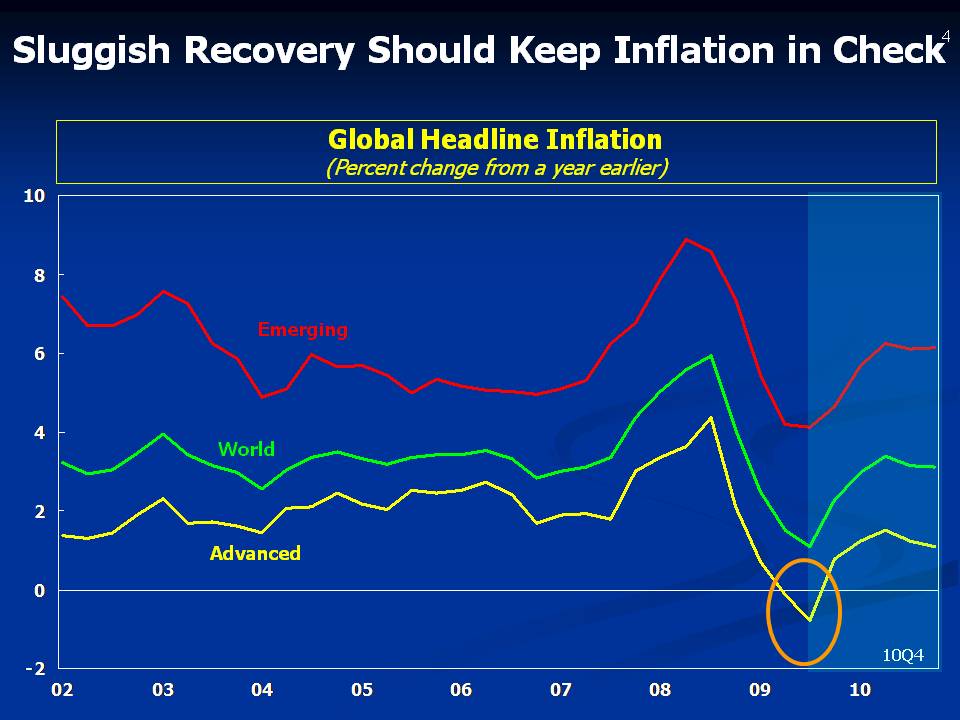

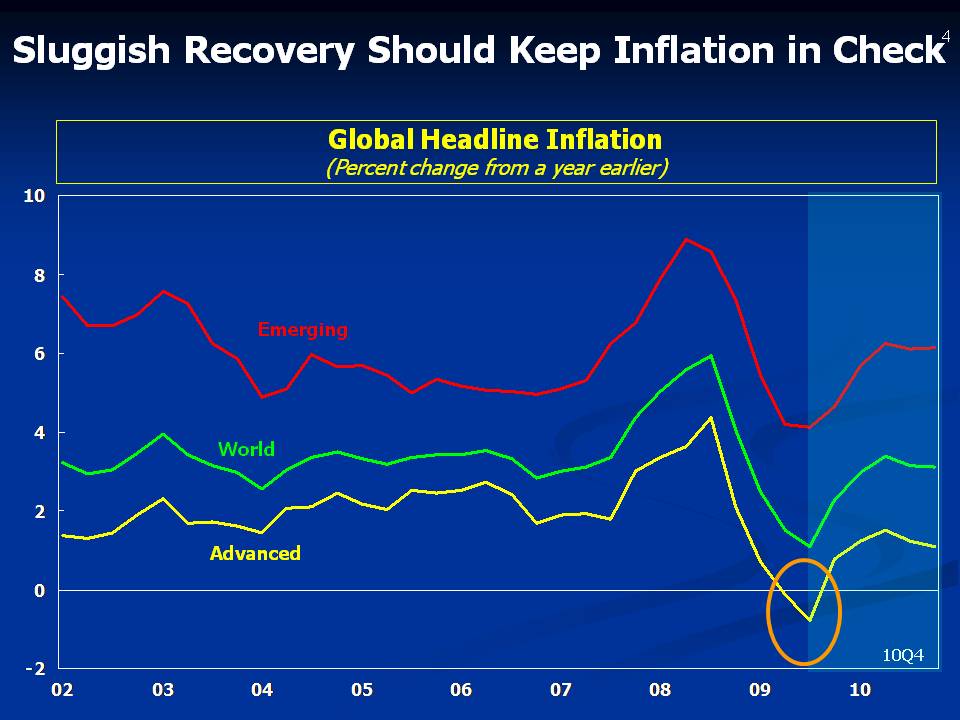

In many economies, inflation is expected to remain contained because of rising unemployment and large output gaps. Capacity utilization in advanced economies will remain low. However, some emerging market economies may face stronger upward price pressure owing to more limited capacity and increased capital inflows, especially in emerging Asia.

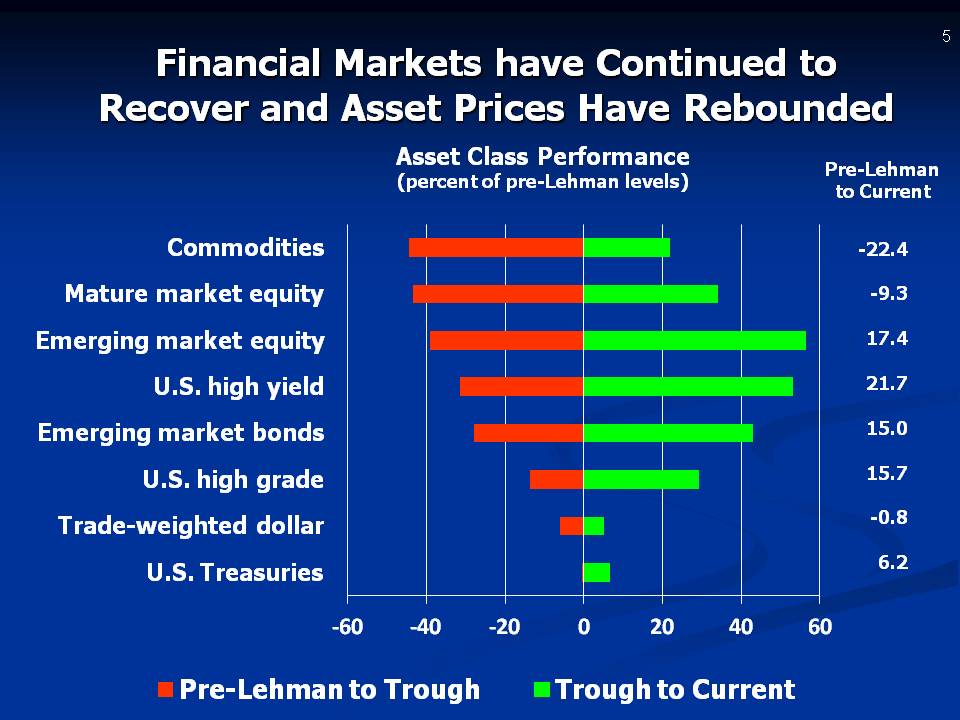

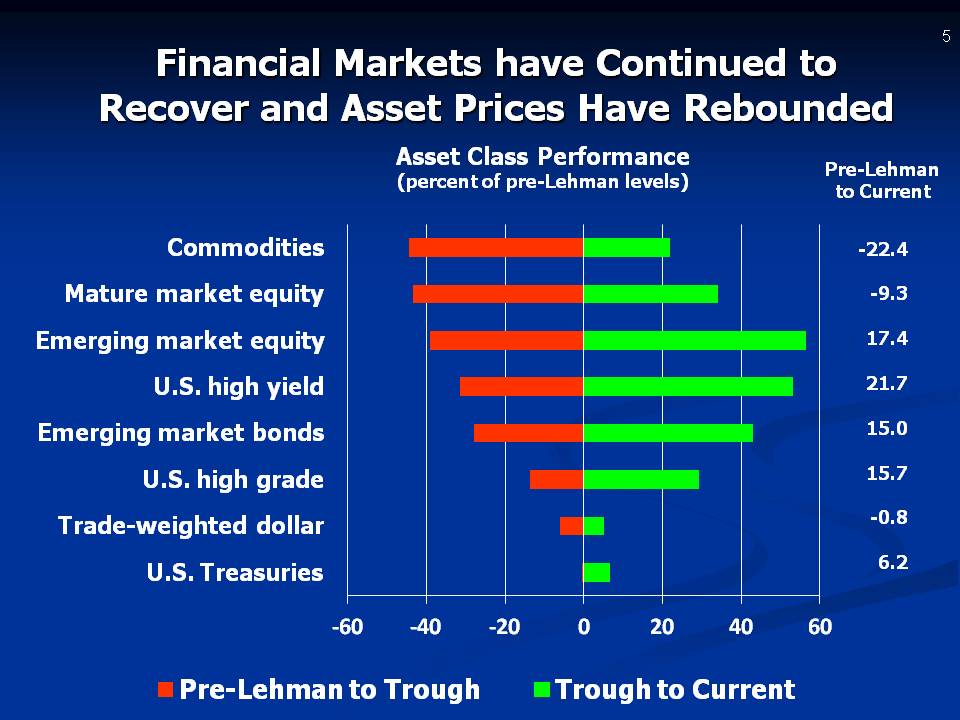

Financial markets have continued to recover, reflecting the improvement in economic prospects. But in many cases, public support remains crucial. In general, risk appetite has returned, and equity markets have improved. Companies have been able to tap market financing directly, but this has not offset the decline in bank financing.

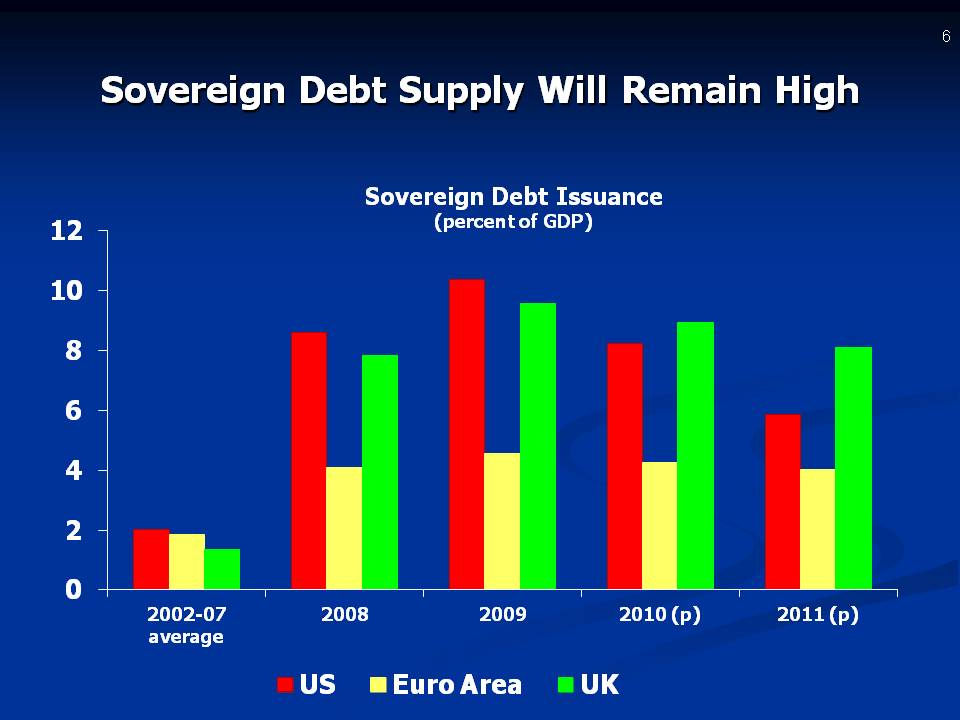

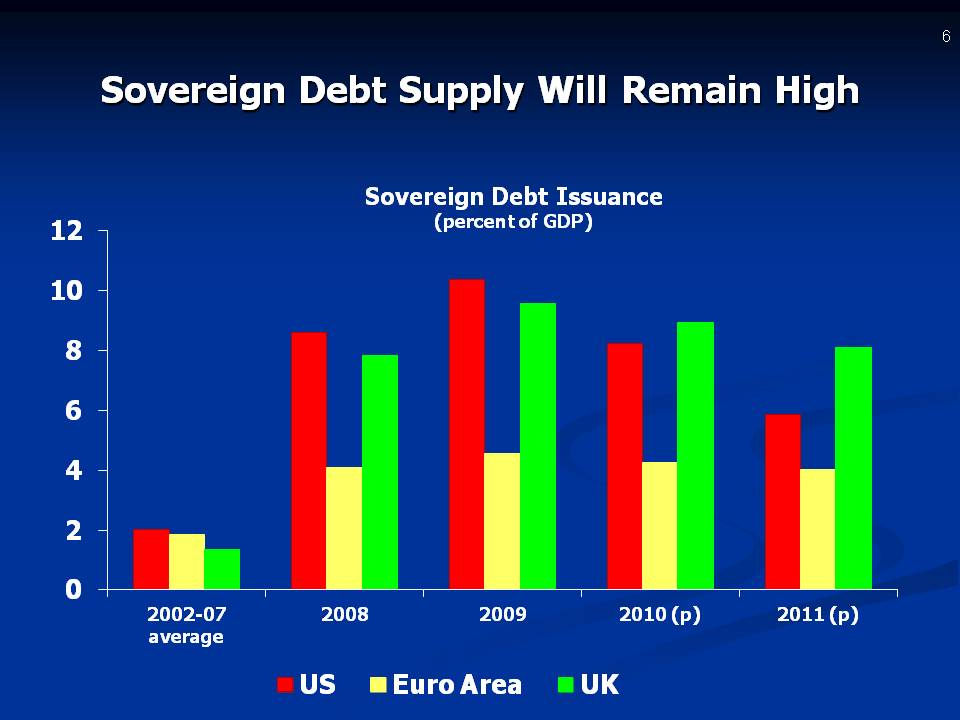

On the negative side, high debt levels are leading to concerns about sovereign risk in some advanced countries. Sovereign debt issuance increased substantially since 2008 in advanced countries. Bond markets have come under pressure in some small European countries as these economies struggle with large government deficits.

II. Outlook for Asia

Let me now turn to prospects in this region.

Growth in Asia is on a solid footing and will be largely driven by buoyant domestic demand. For the region as a whole, growth is likely to reach almost 7 percent in 2010, 1 percentage point higher than our forecast in October. Consumption is projected to be robust, supported by improvements in confidence, asset values and labor markets.

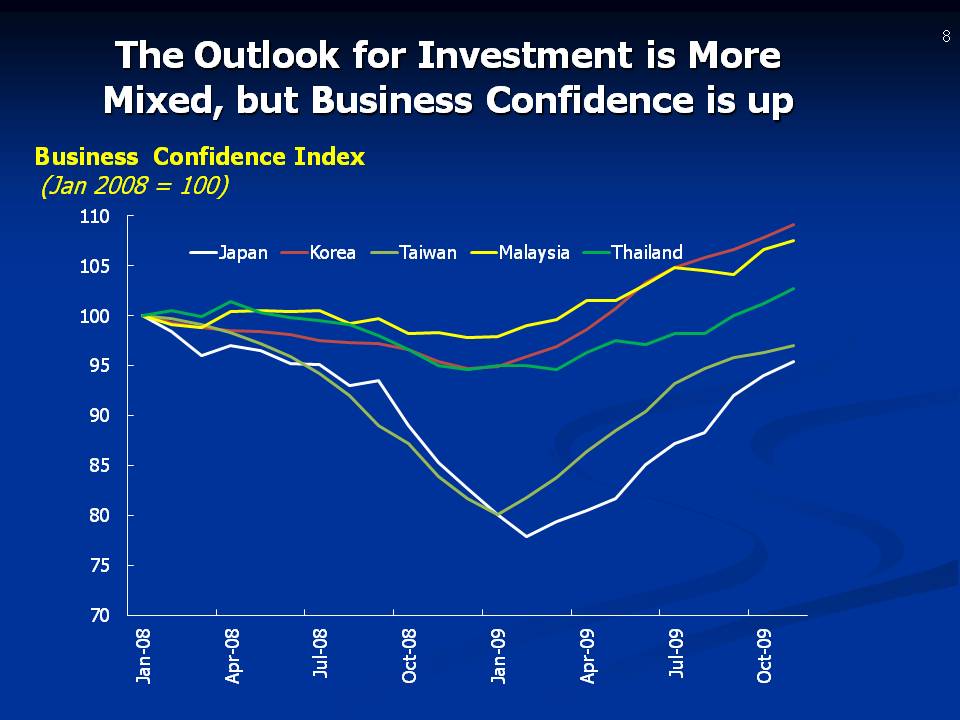

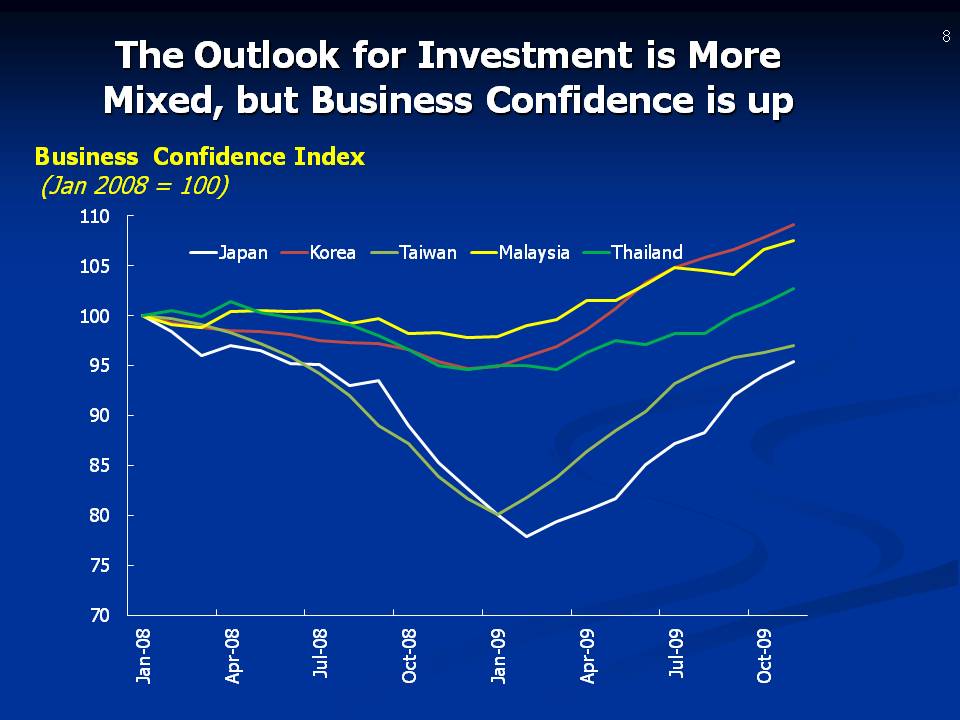

The outlook for private investment is more mixed. In a few Asian economies, investment is expected to pick up significantly in 2010. In Korea, this reflects a fast return to high levels of capacity utilization; in India, a pickup in credit; and in Indonesia, the beginning of large infrastructure projects. Elsewhere, the investment outlook remains weak, partly owing to excess capacity in manufacturing such as in Japan, Malaysia, and Thailand.

The outlook for exports and industrial production remains generally bright, with restocking of inventories in the United States providing a significant boost. However, export volumes remain below pre-crisis levels—with the exception of Korea and China.

In China, growth is expected to reach 10 percent in 2010, following stronger than expected growth of almost 9 percent in 2009. Activity will continue to be driven by strong domestic demand supported by a large policy stimulus. There are also signs that China’s private sector is providing some growth momentum.

III. The Outlook For Commodities

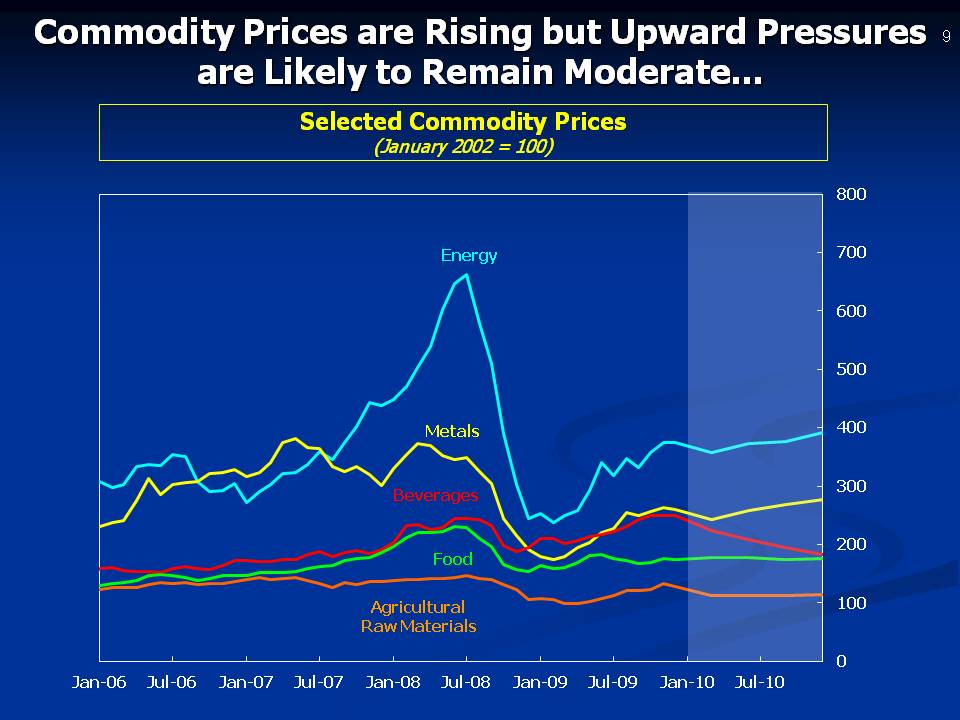

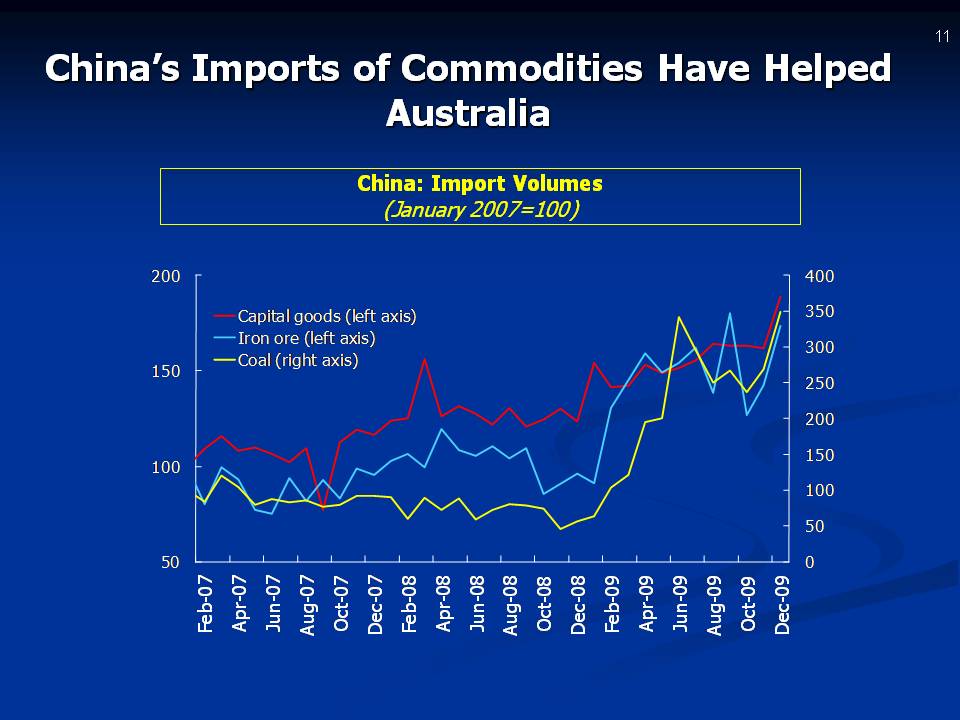

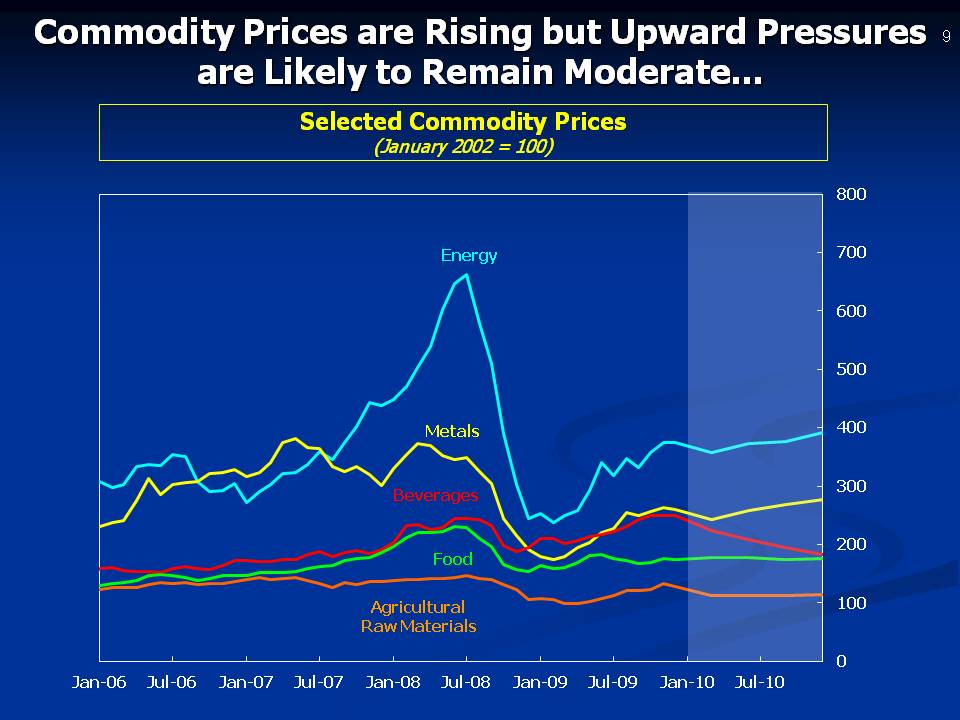

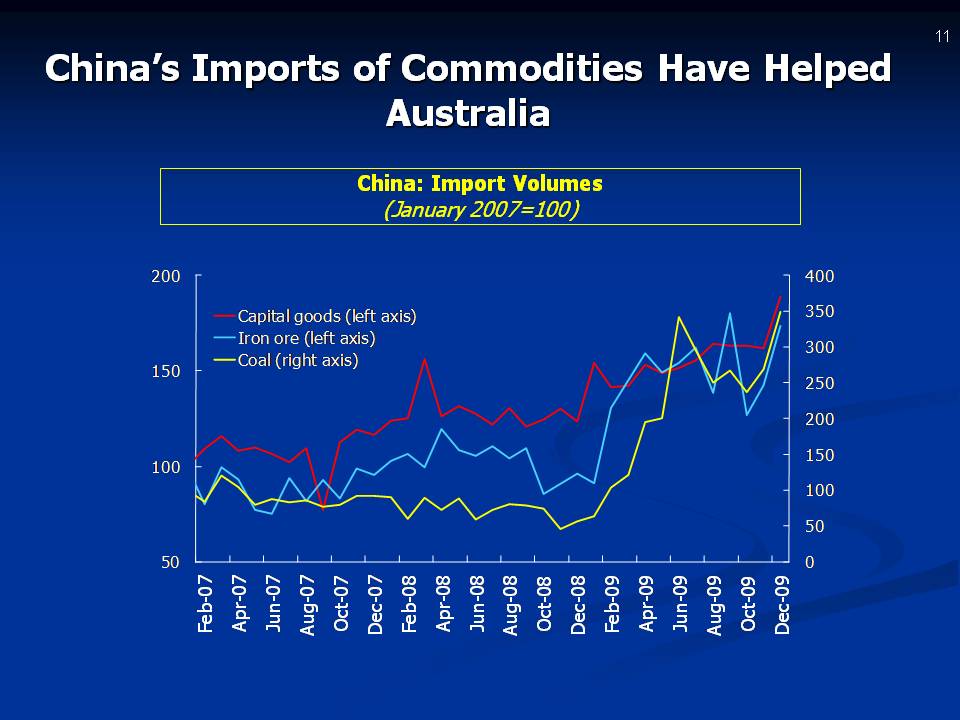

Commodity prices, specially for oil and metals, increased at the onset of the recovery, driven by buoyant growth in emerging economies, especially in Asia, despite high inventories. The rapid growth in China’s commodity imports in 2009 had bolstered expectations for strong Chinese demand across a broad range of commodities. While China’s commodity imports have remained strong, the demand momentum might slow down somewhat this year, given signs of policy tightening in the pipeline and that restocking has run its course.

Looking ahead, commodity prices are expected to rise a bit further on the strength of global demand, especially in emerging economies. The extent of further upward price pressure will also depend on the supply response.

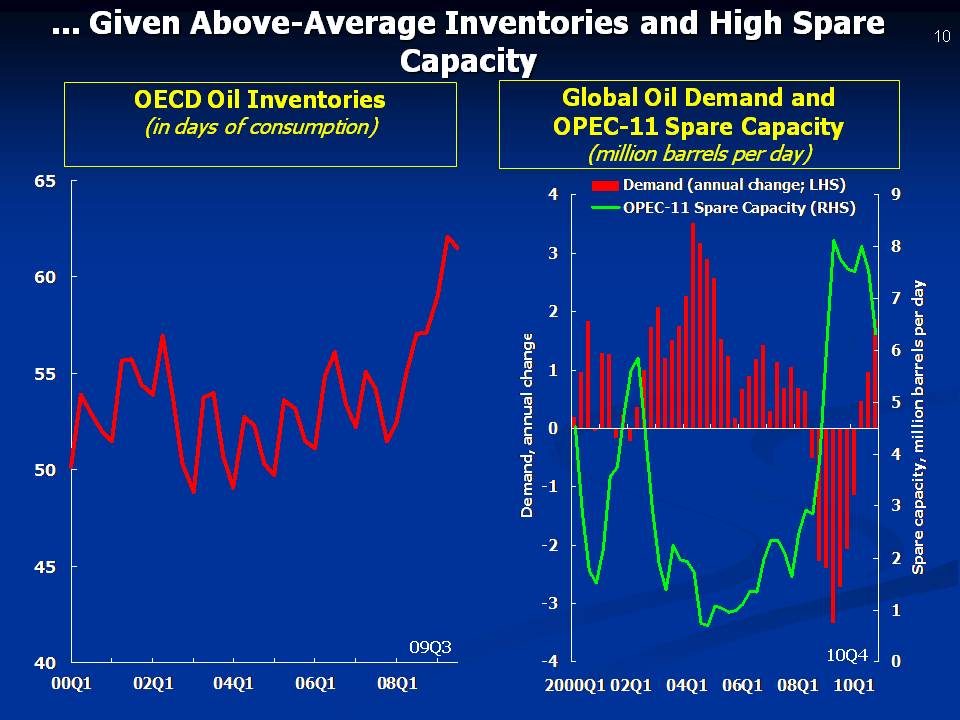

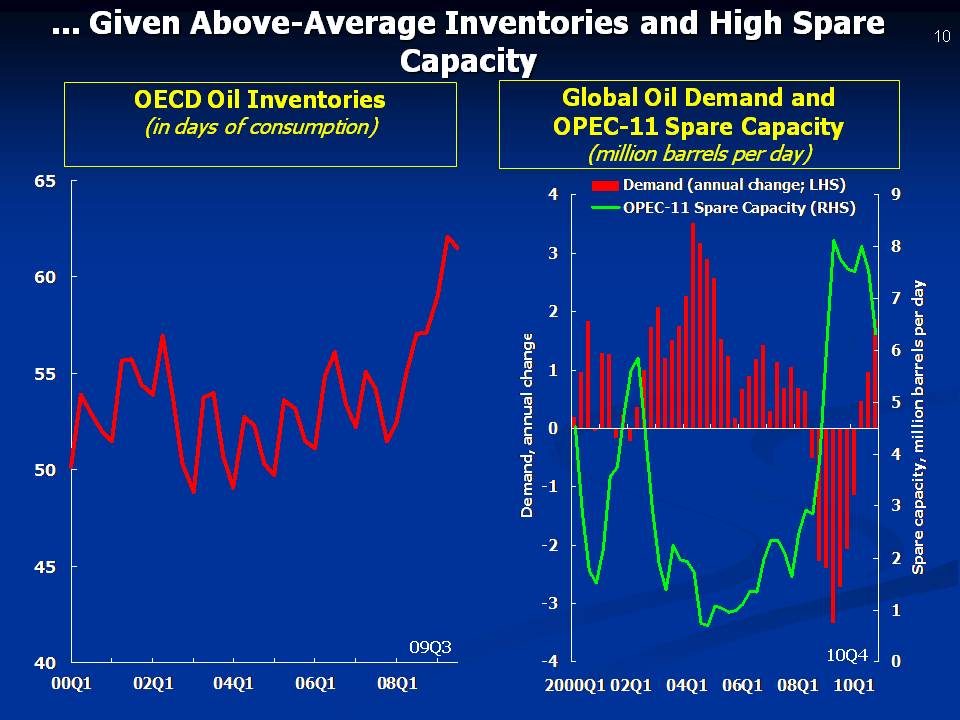

For most commodities, however, upward price pressures are likely to remain moderate, given above average inventories, and significant spare capacity.

Current pricing in commodity derivatives markets suggests that another broad-based commodity price spike is unlikely in the near term. Some food commodities—such as sugar and cocoa—have experienced significant price spikes due to a combination of low inventories and supply shocks in key producers.

IV. Outlook for Australia

Australia has been remarkably resilient to the global turmoil. The economy was indeed hit by the global crisis. But growth was stronger than in any other advanced economy. This resilience is the result of robust demand for commodities, a flexible exchange rate, and a healthy banking sector. Cuts in interest rates and a sizable fiscal stimulus were also key factors.

The Australian economy is expected to grow by 2½ percent in 2010 and 3 percent in 2011, according to our latest forecasts. Growth will be led by domestic demand, both private and public, where we have seen better-than-expected domestic performance in recent months, especially in the labor market.

Strong commodity income prospects are supporting investment in the resource sector in Australia. Some large projects have commenced recently, such as the Gorgon LNG project with investment equivalent to about 3 percent of Australia’s GDP. Other large projects are in the pipeline in Western Australia and the Northern Territory.

In coming years, Australia is likely to continue to benefit from China’s demand for commodities. As you know, a large component of China’s fiscal package consists of public investment in its infrastructure. For example, China plans to build about 20,000 miles of railway by 2020. To give you an idea of the scale of these plans, this is the equivalent of building 10 railway lines from Canberra to Perth. Of course, while benefiting from China’s demand, this presents some risks, as a sharp fall in demand for commodities would hurt the resource sector in Australia, though the likely adjustment in the exchange rate would provide a buffer.

V. Policy Challenges Ahead

Let me turn to the major policy challenges going forward.

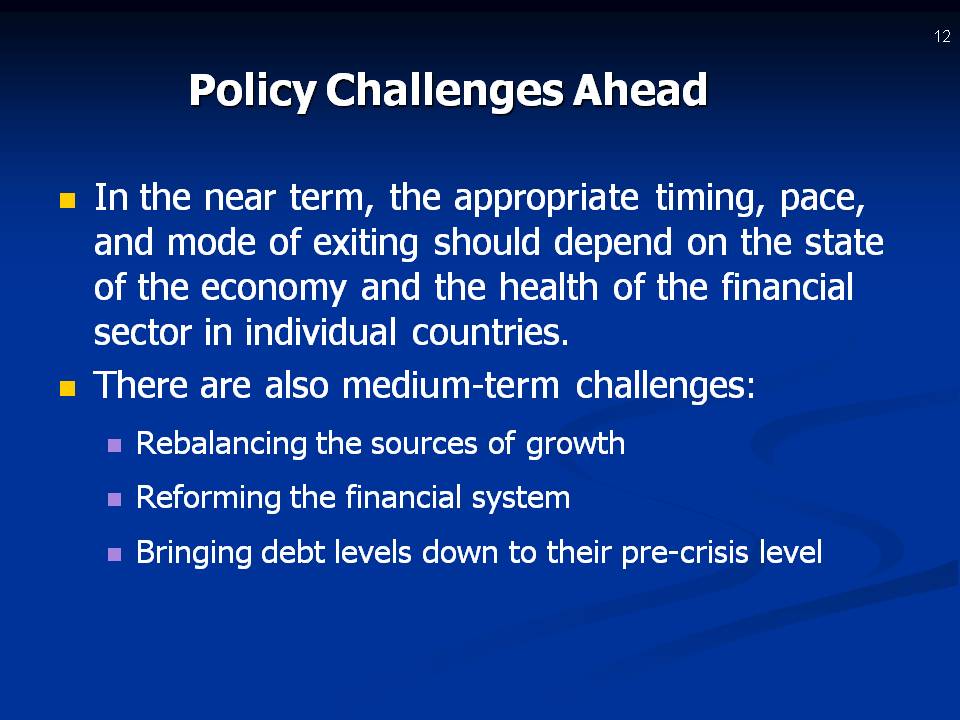

In the near term, policymakers are facing an extremely difficult task in judging the right timing, pace, and sequencing of the exit from policy stimulus. If they act too early and aggressively, the recovery could falter. If the stimulus is left in place for too long, it risks triggering inflationary pressures or asset bubbles. In countries with high public debt, a slow exit from fiscal stimulus could scare financial markets, leading to a loss of investor confidence, especially if medium term plans for fiscal consolidation are not credible.

There are also important medium-term challenges: rebalancing the sources of global growth, reforming the financial system, and bringing debt levels down to their pre-crisis levels.

A. Macroeconomic Policies

Let me elaborate on the challenges with respect to macroeconomic policies. A multispeed recovery means that the appropriate policy response will vary across countries.

In most advanced countries, with recovery expected to be weak, macroeconomic policy- stimulus should be maintained until private demand is self-sustained. Central banks should maintain low interest rates for the foreseeable future, given that underlying inflation is expected to remain subdued and unemployment high for some time.

However, in some major emerging economies in Asia and Latin America, output gaps are rapidly closing and overheating risks have increased. This suggests that an earlier exit is more appropriate for those countries. In India, where the output gap is closing and inflationary pressures have emerged, the authorities have started to tighten monetary conditions. In China, given that the recovery is increasingly well established, we agree with the government that it is time to withdraw some monetary stimulus, given the risks it poses to credit quality and asset price inflation.

Australia entered the global turmoil on solid footing, and thus the exit strategy appears less challenging than elsewhere. Indeed the early recovery, compared to other advanced countries, has allowed the Reserve Bank of Australia to begin normalizing interest rates.

However, the still fragile nature of the global recovery suggests that the withdrawal of the policy stimulus should proceed gradually. On the fiscal front, the Australian government has already begun to unwind its fiscal stimulus, as originally planned. In the medium term, even though public debt is projected to remain low by advanced economy standards, an early return to budget surpluses would be prudent for a number of reasons. It would put Australian on a firmer footing to deal with future shocks and contain the debt servicing costs associated with the private sector’s relatively high external debt. It would also help the budget face longer term challenges from population aging. In the financial sector, conditions have improved significantly and this has allowed the government to announce the removal of guarantees on large deposits and wholesale funding.

In the medium term, a main challenge for the global economy is to rebalance growth. For economies with persistent current account surpluses, this requires a shift toward internal demand. For economies with persistent current account deficits, this requires a shift toward external demand. In Asia, policies would vary across countries. In China, there is a need to establish broader social protection to help reduce households’ precautionary savings, and a need for structural reforms in the service sector. Raising productivity in the service sector will also be key in Japan and Korea. For many ASEAN economies improving the environment for private investment can play an important role in boosting demand. This can be achieved through easier access to credit especially for small and medium enterprises (SME), by removing red tape, and by increasing private public partnership. Greater exchange rate flexibility will also facilitate rebalancing. In the United States and countries in the euro area that have relied excessively on domestic demand-led growth, there is a need to shift resources toward the tradable sector.

B. Financial Sector Policies

Let me refer to another important medium term challenge, which is the reform of the financial system.

Despite much progress since the onset of the crisis, the financial system remains fragile in some countries. In many advanced countries and some hard-hit emerging markets, banks are still stressed.

Designing exits from financial support policies represents a critical challenge. Exiting from support to shorter-term funding markets and liquidity provision could be relatively fast and easy. These facilities are no longer being used in some cases as private market activity revives. However, other facilities may need to remain in place for some time including support of the mortgage market in the US and purchases of government bonds in the UK.

But designing and implementing financial sector reform will require a high degree of political determination and coordination. Early reform would reduce uncertainty and may encourage the resumption of lending.

Global consistency of regulations will be essential for financial stability. It would reduce systemic risk and help ensure a level playing field.

Some emerging market countries will have to design policies to manage a surge of capital inflows. Macroeconomic and prudential policies can be used to address the potential for bubbles at an early stage by limiting a buildup in risks. Limits on leverage, loan-to-value ratios, and well managed margining and collateral systems in securities’ markets will help reduce risks. In addition, some countries will need to consider increasing currency flexibility and other macroeconomic policy adjustments in order to restrain capital inflows that seek to benefit from “one-way bets” in currency markets.

C. Fiscal Policies

The crisis has left scars in the form of large public debt increases, particularly in advanced countries, adding to existing longer term challenges from population aging. The debt increase reflects mostly revenue losses from the recession, not so much the stimulus. Thus, in addition and beyond the question of when the stimulus should end, there is a need for a large medium-term fiscal consolidation.

The strategic goal should be to reverse the rise in debt, not just to stabilize it at post-crisis levels. High debt would lead to higher interest rates, lower potential growth, and less flexibility in responding to shocks. Lowering debt will take several years, as a major primary balance correction is needed, and will involve difficult measures. But history tells us that it can be done.

While, fiscal policies still need to remain supportive of economic activity this year wherever possible, countries with high public debt where sovereign risk has increased should exit earlier from fiscal stimulus. Advanced countries should provide a strong commitment to medium-term fiscal consolidation. While it is too early to exit from fiscal stimulus this year it is not too early to provide credible and detailed fiscal consolidation strategies. There is also a need to start implementing now measures that do not have a negative impact on aggregate demand, for example by increasing the retirement age for public pensions and strengthening budget policies.

VI. Concluding Remarks

Let me conclude by saying that the current crisis is providing important lessons not only with respect to areas that need a substantial overhaul such as financial sector regulation and supervision, but also on the need for greater international cooperation on economic and financial policies. Close policy cooperation amongst the major countries was critical to overcome the most acute period of the crisis. It will continue to be important to ensure a sustained, stronger and balanced recovery.

The G-20—in which Australia is playing a major role—agreed to create an innovative process of mutual assessment of policies centered on shared objectives of strong, balanced and sustainable growth. The IMF is playing a role by providing analytical support for the ongoing policy discussions.

While the path ahead will not be easy, the unprecedented international commitment to find shared solutions to common challenges makes me very confident that we will be able to build a more stable and prosperous world economy.

Thank you.

However, let me emphasize that the recovery is proceeding at different speeds across the various regions of the world. And it remains fragile. We moved from a remarkably synchronized global downturn to a multi-speed recovery. And this poses its own challenges.

In most advanced economies, growth is likely to be sluggish, and still dependent on government support. Output is forecast to expand on average by 2 percent in 2010 and 2½ percent in 2011 in advanced countries. The recovery will be slow by past standards. There are few signs that private demand is self-sustaining on the back of high unemployment—especially in Europe and the US. High public debt in some advanced countries, as well as still fragile financial systems, pose further challenges to the recovery. The situation is better in emerging markets, where growth is expected to reach 6 percent in 2010. The recovery is being led by key emerging Asian economies, notably China, India, Indonesia, and Korea, largely driven by buoyant domestic demand and supported by stimulus measures. Stronger public and private balance sheets than at the onset of the Asian crisis and forceful policy responses supported activity in Asia. In China large stimulus sustained domestic demand, with positive spillovers to other economies. Commodity exporters are also recovering. But emerging markets in Europe are lagging behind.

In many economies, inflation is expected to remain contained because of rising unemployment and large output gaps. Capacity utilization in advanced economies will remain low. However, some emerging market economies may face stronger upward price pressure owing to more limited capacity and increased capital inflows, especially in emerging Asia.

Financial markets have continued to recover, reflecting the improvement in economic prospects. But in many cases, public support remains crucial. In general, risk appetite has returned, and equity markets have improved. Companies have been able to tap market financing directly, but this has not offset the decline in bank financing.

On the negative side, high debt levels are leading to concerns about sovereign risk in some advanced countries. Sovereign debt issuance increased substantially since 2008 in advanced countries. Bond markets have come under pressure in some small European countries as these economies struggle with large government deficits. II. Outlook for Asia Let me now turn to prospects in this region.

Growth in Asia is on a solid footing and will be largely driven by buoyant domestic demand. For the region as a whole, growth is likely to reach almost 7 percent in 2010, 1 percentage point higher than our forecast in October. Consumption is projected to be robust, supported by improvements in confidence, asset values and labor markets.

The outlook for private investment is more mixed. In a few Asian economies, investment is expected to pick up significantly in 2010. In Korea, this reflects a fast return to high levels of capacity utilization; in India, a pickup in credit; and in Indonesia, the beginning of large infrastructure projects. Elsewhere, the investment outlook remains weak, partly owing to excess capacity in manufacturing such as in Japan, Malaysia, and Thailand. The outlook for exports and industrial production remains generally bright, with restocking of inventories in the United States providing a significant boost. However, export volumes remain below pre-crisis levels—with the exception of Korea and China. In China, growth is expected to reach 10 percent in 2010, following stronger than expected growth of almost 9 percent in 2009. Activity will continue to be driven by strong domestic demand supported by a large policy stimulus. There are also signs that China’s private sector is providing some growth momentum. III. The Outlook For Commodities Commodity prices, specially for oil and metals, increased at the onset of the recovery, driven by buoyant growth in emerging economies, especially in Asia, despite high inventories. The rapid growth in China’s commodity imports in 2009 had bolstered expectations for strong Chinese demand across a broad range of commodities. While China’s commodity imports have remained strong, the demand momentum might slow down somewhat this year, given signs of policy tightening in the pipeline and that restocking has run its course.

Looking ahead, commodity prices are expected to rise a bit further on the strength of global demand, especially in emerging economies. The extent of further upward price pressure will also depend on the supply response.

For most commodities, however, upward price pressures are likely to remain moderate, given above average inventories, and significant spare capacity. Current pricing in commodity derivatives markets suggests that another broad-based commodity price spike is unlikely in the near term. Some food commodities—such as sugar and cocoa—have experienced significant price spikes due to a combination of low inventories and supply shocks in key producers. IV. Outlook for Australia Australia has been remarkably resilient to the global turmoil. The economy was indeed hit by the global crisis. But growth was stronger than in any other advanced economy. This resilience is the result of robust demand for commodities, a flexible exchange rate, and a healthy banking sector. Cuts in interest rates and a sizable fiscal stimulus were also key factors. The Australian economy is expected to grow by 2½ percent in 2010 and 3 percent in 2011, according to our latest forecasts. Growth will be led by domestic demand, both private and public, where we have seen better-than-expected domestic performance in recent months, especially in the labor market. Strong commodity income prospects are supporting investment in the resource sector in Australia. Some large projects have commenced recently, such as the Gorgon LNG project with investment equivalent to about 3 percent of Australia’s GDP. Other large projects are in the pipeline in Western Australia and the Northern Territory.

In coming years, Australia is likely to continue to benefit from China’s demand for commodities. As you know, a large component of China’s fiscal package consists of public investment in its infrastructure. For example, China plans to build about 20,000 miles of railway by 2020. To give you an idea of the scale of these plans, this is the equivalent of building 10 railway lines from Canberra to Perth. Of course, while benefiting from China’s demand, this presents some risks, as a sharp fall in demand for commodities would hurt the resource sector in Australia, though the likely adjustment in the exchange rate would provide a buffer. V. Policy Challenges Ahead Let me turn to the major policy challenges going forward.

In the near term, policymakers are facing an extremely difficult task in judging the right timing, pace, and sequencing of the exit from policy stimulus. If they act too early and aggressively, the recovery could falter. If the stimulus is left in place for too long, it risks triggering inflationary pressures or asset bubbles. In countries with high public debt, a slow exit from fiscal stimulus could scare financial markets, leading to a loss of investor confidence, especially if medium term plans for fiscal consolidation are not credible. There are also important medium-term challenges: rebalancing the sources of global growth, reforming the financial system, and bringing debt levels down to their pre-crisis levels. A. Macroeconomic Policies Let me elaborate on the challenges with respect to macroeconomic policies. A multispeed recovery means that the appropriate policy response will vary across countries. In most advanced countries, with recovery expected to be weak, macroeconomic policy- stimulus should be maintained until private demand is self-sustained. Central banks should maintain low interest rates for the foreseeable future, given that underlying inflation is expected to remain subdued and unemployment high for some time. However, in some major emerging economies in Asia and Latin America, output gaps are rapidly closing and overheating risks have increased. This suggests that an earlier exit is more appropriate for those countries. In India, where the output gap is closing and inflationary pressures have emerged, the authorities have started to tighten monetary conditions. In China, given that the recovery is increasingly well established, we agree with the government that it is time to withdraw some monetary stimulus, given the risks it poses to credit quality and asset price inflation. Australia entered the global turmoil on solid footing, and thus the exit strategy appears less challenging than elsewhere. Indeed the early recovery, compared to other advanced countries, has allowed the Reserve Bank of Australia to begin normalizing interest rates. However, the still fragile nature of the global recovery suggests that the withdrawal of the policy stimulus should proceed gradually. On the fiscal front, the Australian government has already begun to unwind its fiscal stimulus, as originally planned. In the medium term, even though public debt is projected to remain low by advanced economy standards, an early return to budget surpluses would be prudent for a number of reasons. It would put Australian on a firmer footing to deal with future shocks and contain the debt servicing costs associated with the private sector’s relatively high external debt. It would also help the budget face longer term challenges from population aging. In the financial sector, conditions have improved significantly and this has allowed the government to announce the removal of guarantees on large deposits and wholesale funding. In the medium term, a main challenge for the global economy is to rebalance growth. For economies with persistent current account surpluses, this requires a shift toward internal demand. For economies with persistent current account deficits, this requires a shift toward external demand. In Asia, policies would vary across countries. In China, there is a need to establish broader social protection to help reduce households’ precautionary savings, and a need for structural reforms in the service sector. Raising productivity in the service sector will also be key in Japan and Korea. For many ASEAN economies improving the environment for private investment can play an important role in boosting demand. This can be achieved through easier access to credit especially for small and medium enterprises (SME), by removing red tape, and by increasing private public partnership. Greater exchange rate flexibility will also facilitate rebalancing. In the United States and countries in the euro area that have relied excessively on domestic demand-led growth, there is a need to shift resources toward the tradable sector. B. Financial Sector Policies Let me refer to another important medium term challenge, which is the reform of the financial system.

Despite much progress since the onset of the crisis, the financial system remains fragile in some countries. In many advanced countries and some hard-hit emerging markets, banks are still stressed. Designing exits from financial support policies represents a critical challenge. Exiting from support to shorter-term funding markets and liquidity provision could be relatively fast and easy. These facilities are no longer being used in some cases as private market activity revives. However, other facilities may need to remain in place for some time including support of the mortgage market in the US and purchases of government bonds in the UK. But designing and implementing financial sector reform will require a high degree of political determination and coordination. Early reform would reduce uncertainty and may encourage the resumption of lending. Global consistency of regulations will be essential for financial stability. It would reduce systemic risk and help ensure a level playing field. Some emerging market countries will have to design policies to manage a surge of capital inflows. Macroeconomic and prudential policies can be used to address the potential for bubbles at an early stage by limiting a buildup in risks. Limits on leverage, loan-to-value ratios, and well managed margining and collateral systems in securities’ markets will help reduce risks. In addition, some countries will need to consider increasing currency flexibility and other macroeconomic policy adjustments in order to restrain capital inflows that seek to benefit from “one-way bets” in currency markets. C. Fiscal Policies The crisis has left scars in the form of large public debt increases, particularly in advanced countries, adding to existing longer term challenges from population aging. The debt increase reflects mostly revenue losses from the recession, not so much the stimulus. Thus, in addition and beyond the question of when the stimulus should end, there is a need for a large medium-term fiscal consolidation. The strategic goal should be to reverse the rise in debt, not just to stabilize it at post-crisis levels. High debt would lead to higher interest rates, lower potential growth, and less flexibility in responding to shocks. Lowering debt will take several years, as a major primary balance correction is needed, and will involve difficult measures. But history tells us that it can be done. While, fiscal policies still need to remain supportive of economic activity this year wherever possible, countries with high public debt where sovereign risk has increased should exit earlier from fiscal stimulus. Advanced countries should provide a strong commitment to medium-term fiscal consolidation. While it is too early to exit from fiscal stimulus this year it is not too early to provide credible and detailed fiscal consolidation strategies. There is also a need to start implementing now measures that do not have a negative impact on aggregate demand, for example by increasing the retirement age for public pensions and strengthening budget policies. VI. Concluding Remarks Let me conclude by saying that the current crisis is providing important lessons not only with respect to areas that need a substantial overhaul such as financial sector regulation and supervision, but also on the need for greater international cooperation on economic and financial policies. Close policy cooperation amongst the major countries was critical to overcome the most acute period of the crisis. It will continue to be important to ensure a sustained, stronger and balanced recovery. The G-20—in which Australia is playing a major role—agreed to create an innovative process of mutual assessment of policies centered on shared objectives of strong, balanced and sustainable growth. The IMF is playing a role by providing analytical support for the ongoing policy discussions. While the path ahead will not be easy, the unprecedented international commitment to find shared solutions to common challenges makes me very confident that we will be able to build a more stable and prosperous world economy. Thank you. |

IMF EXTERNAL RELATIONS DEPARTMENT

| Public Affairs | Media Relations | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-mail: | publicaffairs@imf.org | E-mail: | media@imf.org | |

| Fax: | 202-623-6220 | Phone: | 202-623-7100 | |