China’s widening trade surplus and the growing US trade deficit since the pandemic have renewed concerns about global imbalances and fueled an intense debate on their causes and consequences. There are increasing worries that China’s external surpluses result from industrial policy measures designed to stimulate exports and support economic growth amid weak domestic demand. Some worry that the resulting overcapacity could lead to a “China shock 2.0”—a surge of exports that would displace workers and hurt industrial activity elsewhere.

This trade and industrial policy view of external balances is incomplete at best and should be replaced with a macro view. External balances are ultimately determined by macroeconomic fundamentals, while the link to trade and industrial policy is more tenuous. To understand the pattern of global external imbalances, we need to understand the macroeconomic drivers of desired saving relative to desired investment, not only in China, but also in the rest of the world including, importantly, the United States. While other countries contribute to global imbalances, the United States and China together account about one-third of the global current account balance.

Macroeconomic forces

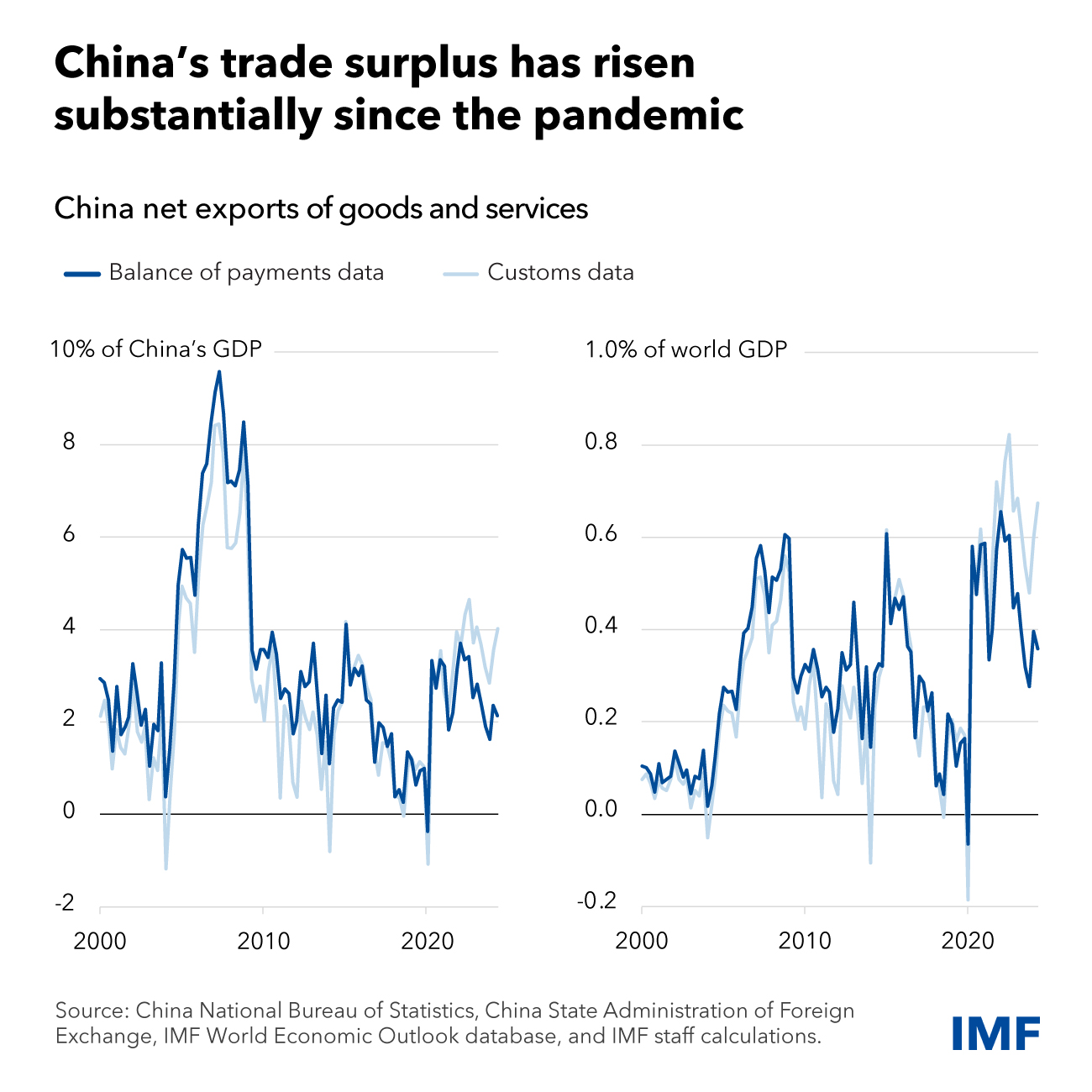

China’s trade surplus increased substantially at the beginning of the pandemic. Initially exports of medical equipment surged and consumers around the world increased purchases of goods relative to services due to social distancing. Then domestic demand in China weakened substantially starting in late 2021 following a large-scale property market correction and repeated lockdowns in 2022 that hurt consumer confidence.

The resulting drag on China’s real economy has been significant as household saving rates increased and investment contracted. At the same time that domestic demand in China weakened, global demand was boosted by significant dissaving—particularly in the United States, where the fiscal deficit grew substantially relative to the pre-pandemic era and the household saving rate halved.

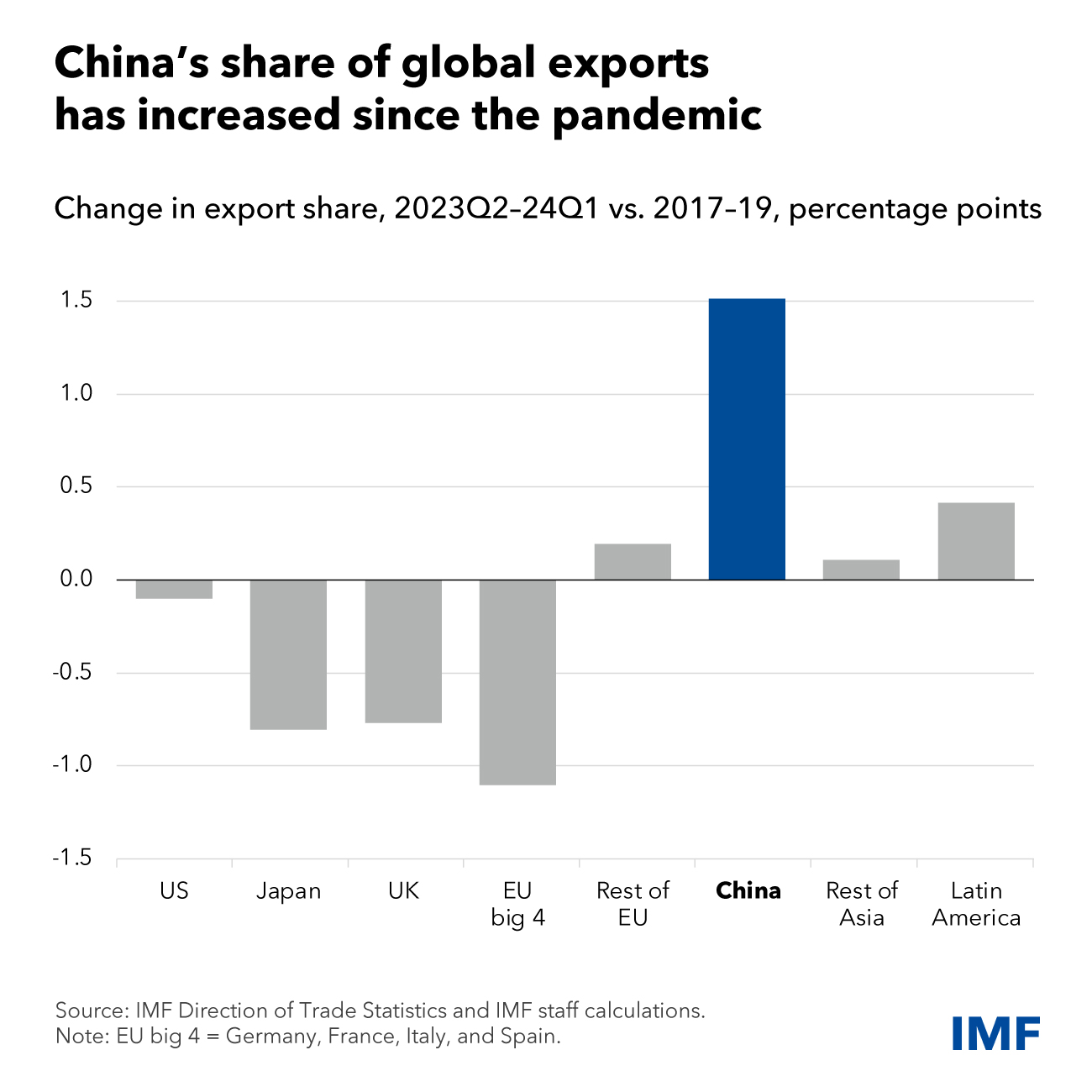

The result is that China’s trade balance now stands at between 2 percent and 4 percent of gross domestic product, depending on the methodology (see China Article IV for details of the differences in methodology). This composition reflects both weak imports and a large rise in China’s global export share.

The trade surplus as a share of economic output is smaller than during the “China Shock” of the 2000s (at its peak, around 10 percent of China’s GDP). However, China now accounts for a substantially larger share of the global economy, so much so that even though its trade surplus is smaller relative to its economy, as a share of global output it has remained fairly stable over time. Hence spillovers from trade developments in China continue to be quite sizable for the rest of the world.

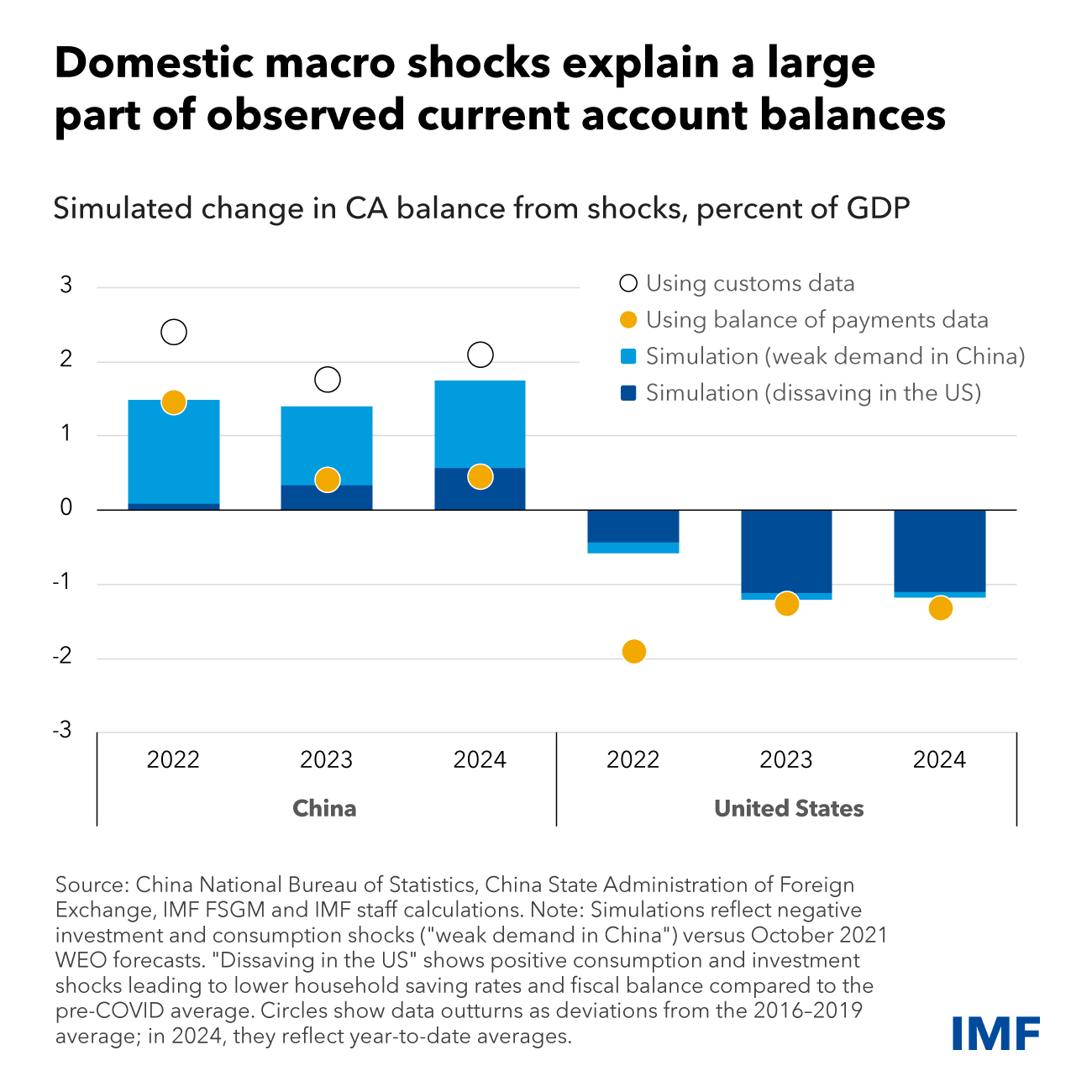

Our analysis—stylized simulations using the IMF’s Group of Twenty model—illustrates that macroeconomic factors are driving these external developments. These include negative domestic demand shocks in China, due to the property market downturn and low household confidence, as well as a dissaving shock in the United States due to elevated government and personal spending.

This “macro” view predicts outcomes close to what the data show. Largely because of weak domestic demand, China’s current account surplus is boosted by about 1.5 percentage points, close to the increase seen in the data relative to its pre-pandemic level. The persistent surge in China’s domestic saving results in a large depreciation of its real effective exchange rate, consistent with data since 2021. This relative price adjustment supports export growth and depresses import demand.

The US presents a mirror image. Largely because of strong domestic demand, the US current account balance deteriorates by around 1 percentage point in the model—close to the decrease seen in the data relative to its pre-pandemic level.

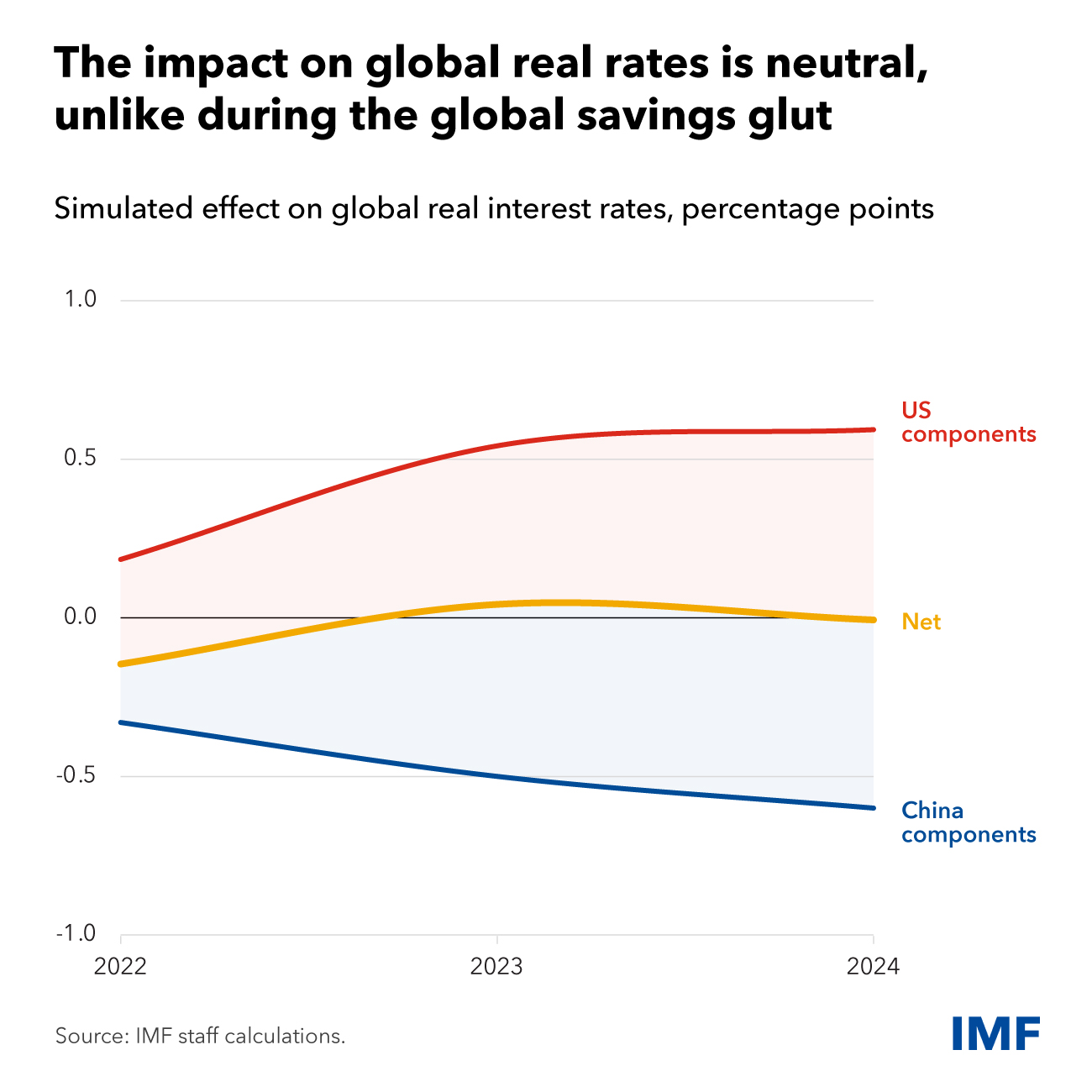

Importantly, the persistent decline in US domestic saving leads to a rise in US real interest rates that broadly offsets the negative effect of increased Chinese saving on global rates.

Two important lessons emerge:

- Unlike the 2000s, when excess saving originating in emerging Asian economies contributed to global imbalances and depressed world interest rates, there is no global savings glut this time. Global real rates outside China have increased, not decreased.

- The contribution of the Chinese saving shock to the US external balance is small, and so is that of the US dissaving shock to China’s trade balance. External surpluses and deficits in both countries are mostly homegrown.

Homegrown surpluses and deficits call for homegrown solutions that require setting the macro dials appropriately. Sustained growth in China will come from addressing long-standing domestic imbalances such as the property sector’s continued drag on activity or the challenges of an aging population. Attempts at stimulating growth through its external sector are likely to face significant headwinds. The economy is just too large—a sign of its success—to generate much growth from exports. This is also reflected in our medium-term outlook for China, where an export-led growth model is no longer the economy’s blueprint.

More fundamentally, China needs to rebalance its economy through comprehensive macro and structural reforms. The right approach consists of a multi-pronged strategy that includes implementing a policy package to make the property sector adjustment less costly; a demand-side stimulus focused on households; and reforms to structurally strengthen safety nets, reduce income inequality, and improve resource allocation.

For the United States, external balances will benefit from a significant fiscal adjustment. This can be achieved through a variety of ways, including raising indirect taxes, progressively increasing income taxes, eliminating a range of tax expenditures, and reforming entitlement programs.

Subsidies and industrial policy

But what about industrial and trade policies spurring concerns among trading partners about “overcapacity” in China? Regardless of the overall external balance, state support in certain exporting or import-competing sectors can boost activity in those sectors. They may also significantly improve cost competitiveness through learning by doing or economies of scale. The resulting macroeconomic impact could be significant, depending on the size and criticality of the sector and the magnitude of the subsidy.

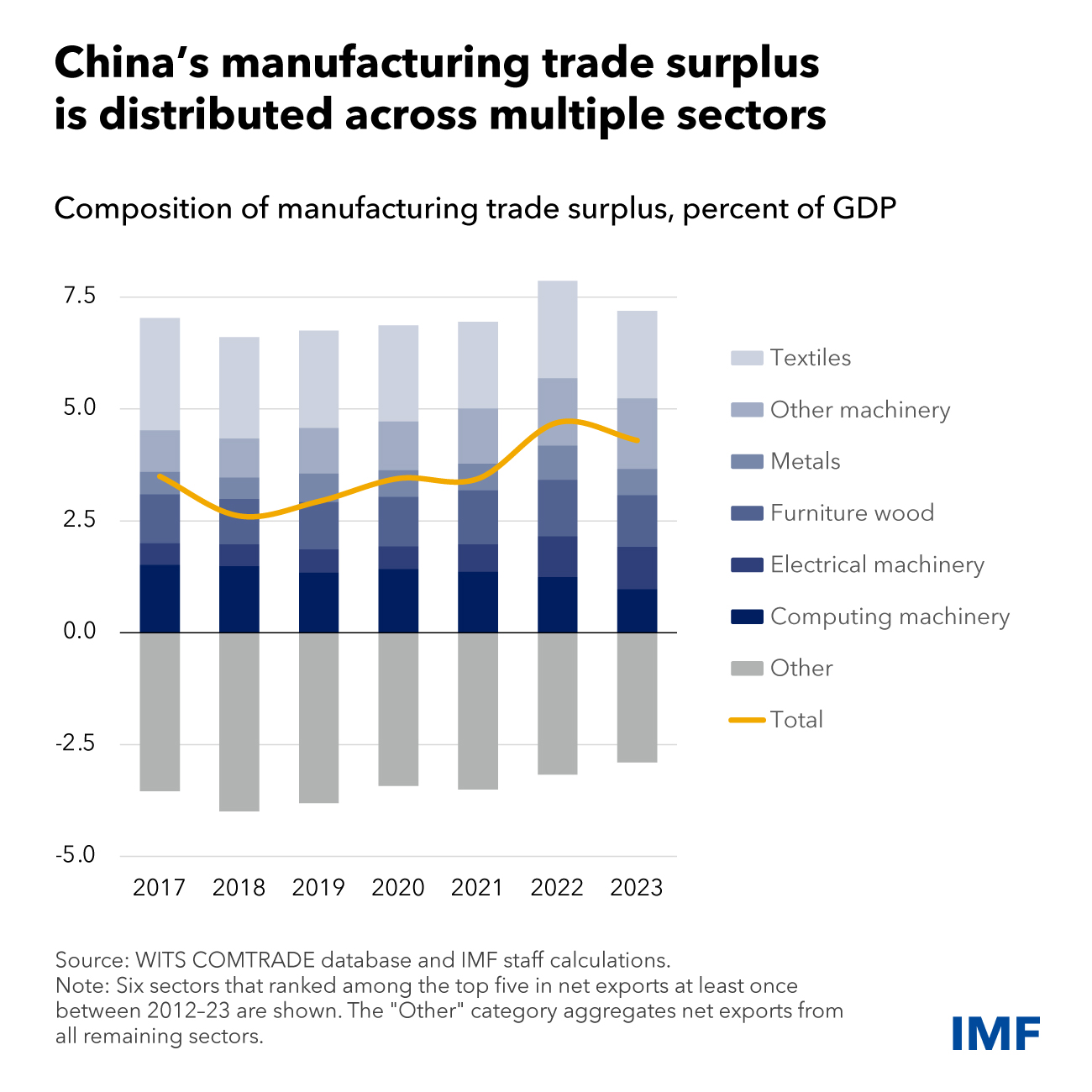

Data from the Global Trade Alert show that China has implemented around 5,400 subsidy policies from 2009 to 2022, which is equal to about two thirds of all the measures adopted by G20 advanced economies combined. China’s subsidies are concentrated in priority sectors such as software, automobiles, transportation, semiconductors, and more recently, green technology. Yet, the country’s manufacturing trade surplus is not concentrated among any specific industries and the share of the major sectoral contributors has remained fairly stable over time. Subsidies for electric vehicles and other green technology goods have received widespread attention as exports have surged. Indeed, China was the largest manufacturer of EVs in 2023, producing 8.9 million EVs (about two-thirds of annual global EV production) and exporting 1.2 million—making China the leading exporter of electric vehicles. But as of now these exports only account for about 1 percent of Chinese goods.

Staff analysis indicates that these subsidies do play some role in generating international trade spillovers in the respective sectors. After the introduction of a subsidy, China’s exports of subsidized products are 1 percent higher than those of non-subsidized products. Imports of subsidized products are lower, indicating some domestic substitution. The estimated effects are however modest, suggesting that industrial policies have a limited impact on aggregate external balances. That said, lack of data on legacy subsidies, on the monetary value of subsidies, and on how they are financed and deployed does not allow a full assessment of their aggregate impact. As the World Trade Organization’s recent Trade Policy Review of China pointed out, lack of transparency on subsidy policies in China hinders a comprehensive and informed assessment of their global implications. Steps should be taken by the authorities to address these data gaps.

Two additional aspects are important.

First, beyond China, many countries like the United States, are rapidly ramping up their use of industrial policies. Emerging economies, where such measures were historically more prevalent, still retain a large number of them. Even if they may not be the major factor driving countries’ overall external surpluses, they still matter. These may well generate sizable negative spillovers in trading partners, by undercutting the competitiveness and market access in other countries, exacerbating trade tensions. To avoid undue distortions, both domestically and internationally, industrial policies in all countries should be confined to narrow objectives: those where externalities or market failures prevent effective market solutions and be consistent with international obligations.

Second, to the extent industrial policies distort the level playing field, some redress is appropriate and should be obtained through WTO-consistent tools. Multilateral trade rules also provide some guardrails on subsidies, allowing for remedies either through multilateral dispute settlement or countervailing duties.

At the same time, longstanding and recently-exposed gaps remain in international trading rules, shaped by developments such as the emergence of global value chains; the global importance of economies in which the state plays a central role, and the urgent challenge of climate change. Unilateral responses through tariffs, nontariff barriers, and domestic content provisions are the wrong solutions. They increase the risks of retaliation, and policy uncertainty, undermine the multilateral trading system, weaken global supply chains and increase geo-economic fragmentation. Instead, governments should come together to strengthen WTO rules and norms in these areas.