Recent price swings reflected largely energy- and supply-related shocks rather than macroeconomic overheating

As inflation began to rise in 2021, most policymakers and analysts predicted that the increase would be neither particularly large nor persistent. But by 2022, inflation had become an acute problem for central bankers. Then, after some of the sharpest and most synchronized monetary policy tightening on record, world inflation ebbed almost as suddenly as it had risen.

We see two broad explanations. The first stresses that inflation rose at the same time in most countries because they were subjected—to varying degrees—to a similar sequence of shocks: the pandemic, mobility restrictions, and associated economic policy measures, especially the extent of fiscal and monetary support. This emphasizes domestic drivers. More fiscal and monetary support, tighter labor markets, or less-well-anchored inflation expectations would translate into higher inflation.

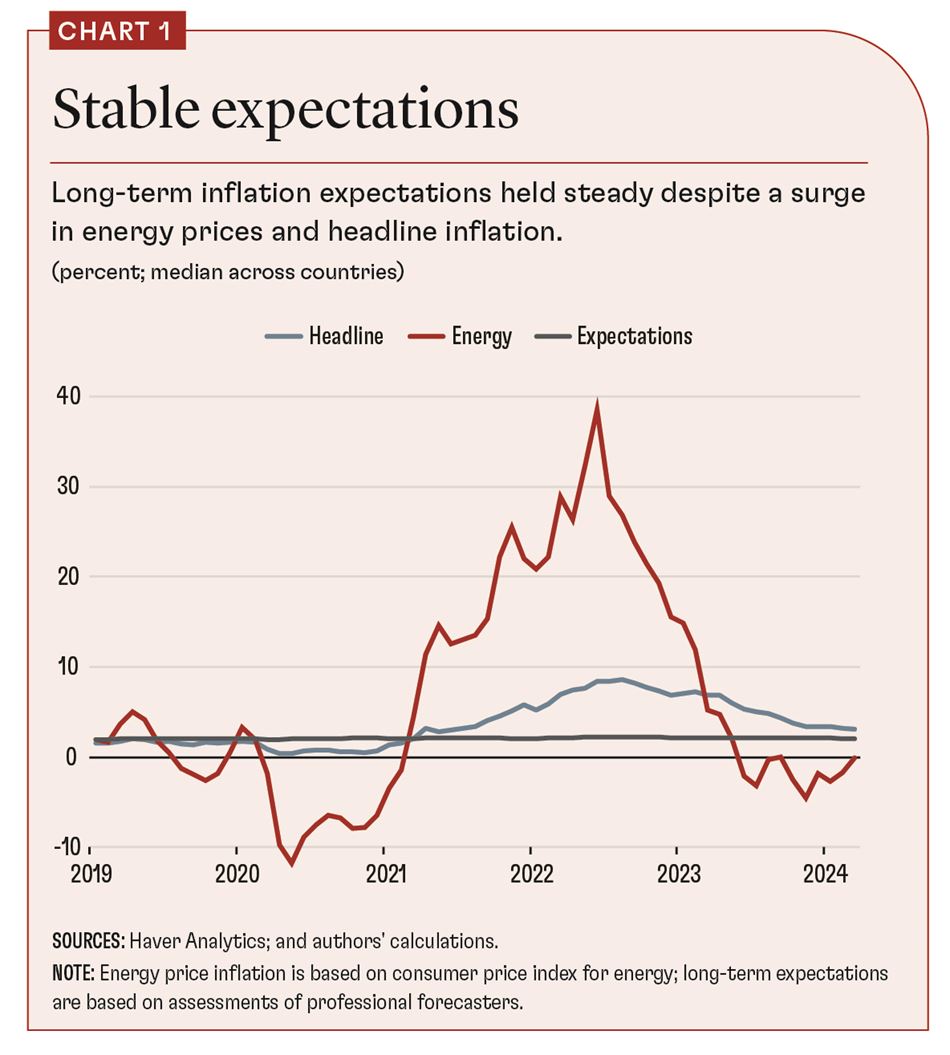

The second stresses that inflation rose everywhere at the same time, not because local shocks were identical across countries, but because global causes were at play. The surge in energy and food prices, intensified by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, triggered an energy crisis akin to the 1970s oil shocks. Geopolitics was the cause of both series of events. And it’s true that global energy prices and headline inflation rose together even as long-term inflation expectations held steady (see Chart 1).

Our recent research (Dao and others, forthcoming) covering 21 advanced and emerging market economies sheds light on these competing explanations by decomposing headline consumer price inflation into underlying (core) inflation and headline shocks—deviations of headline from core inflation. We explain core inflation by long-term inflation expectations and broad measures of macroeconomic slack, such as the unemployment rate, the output gap, or the ratio of vacancies to unemployment. We explain headline inflation shocks by large price changes in particular industries, such as food, energy, or shipping, and by measures of supply-chain disruptions. We also allow for the pass-through over time from these industry price shocks to core inflation, which can occur through the effects of headline inflation on wages and other production costs.

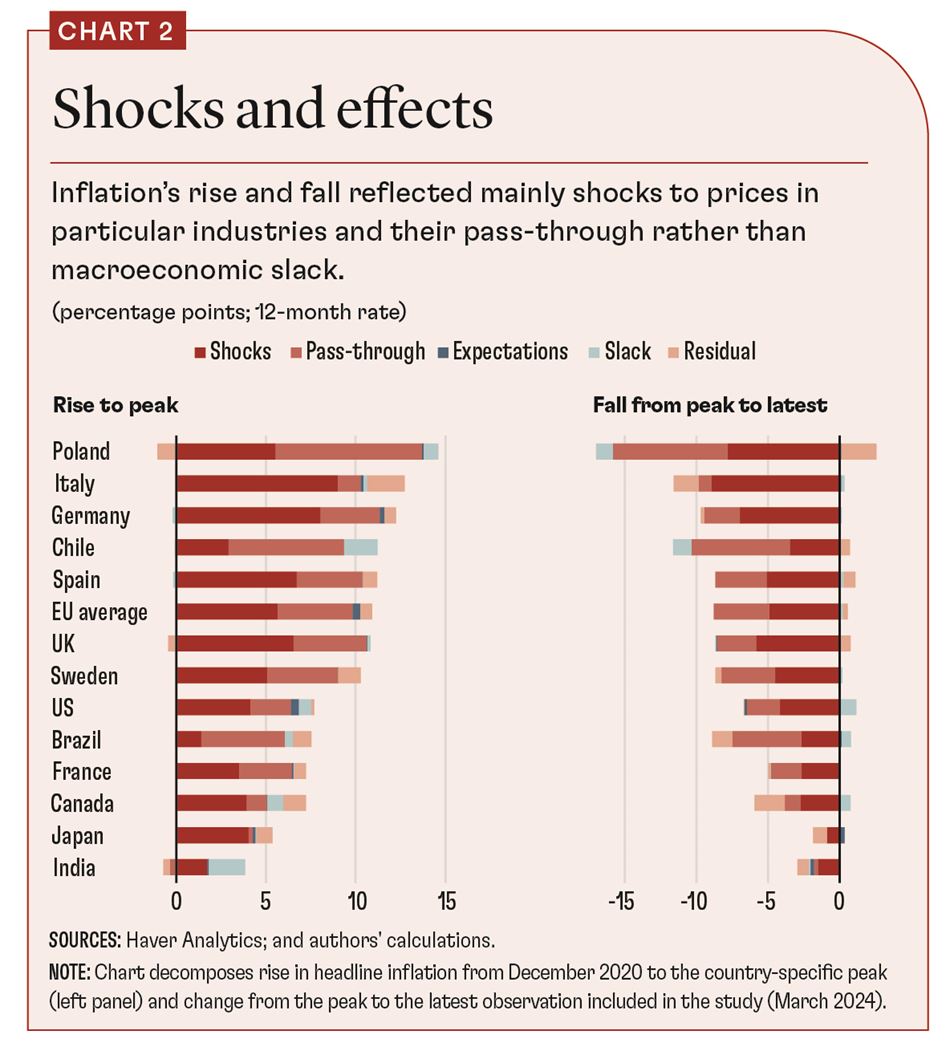

Putting the different pieces together, we estimate the respective contributions of headline shocks, their pass-through into core inflation, broader measures of macroeconomic slack, and changes in long-term expectations to the rise and fall of inflation across countries.

Overall, we find that headline shocks and their pass-through into core inflation account for most of the rise and fall of inflation. Broader measures of macroeconomic slack and changes in longer-term inflation expectations generally contribute little (see Chart 2).

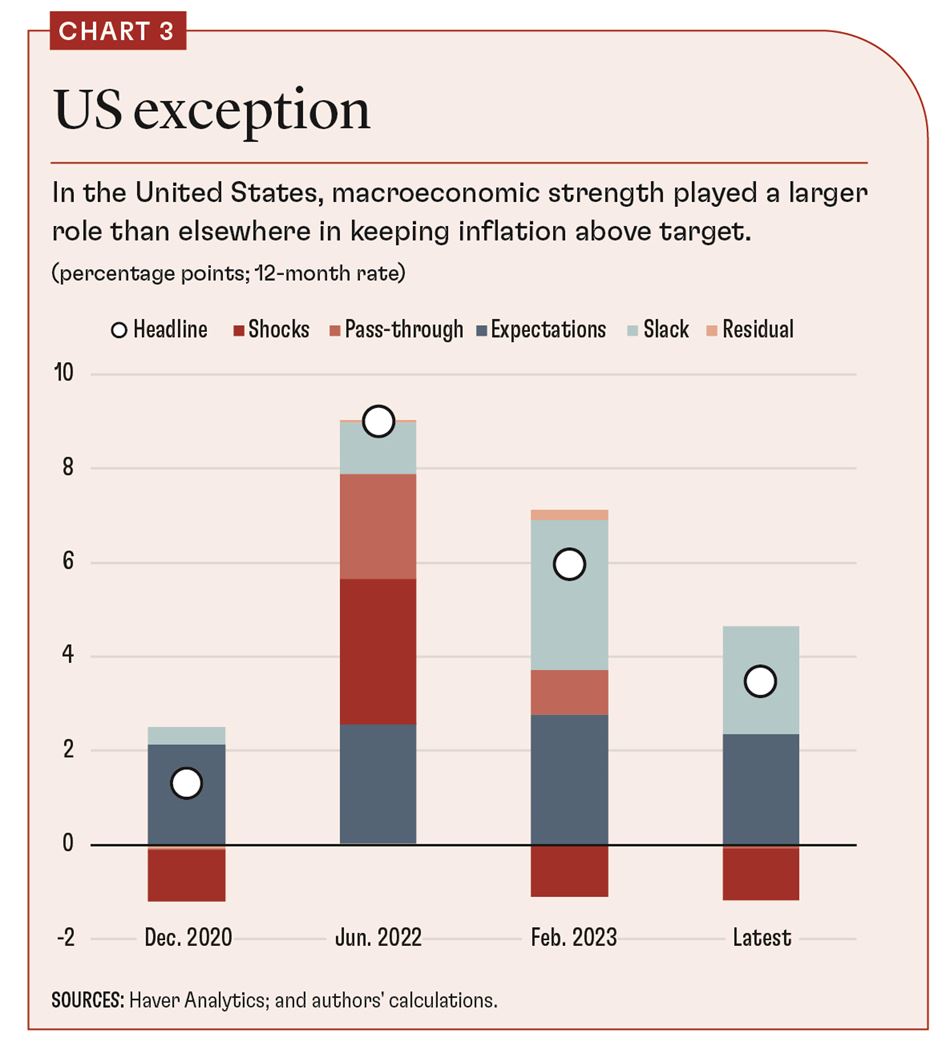

The United States is a significant exception. The contribution of broad macroeconomic tightness to inflation remains greater than in other economies despite the significant cooling of the labor market since early 2023. The fall in US headline inflation since February 2023 reflects equally the cooling of the broader economy and the fading pass-through from earlier headline shocks (see Chart 3).

The bottom line is that inflation’s rise and fall reflected primarily global drivers, but local circumstances mattered too. We find, for example, that differences in local energy price policies, including subsidies for people and businesses, explain differences in the role of energy price shocks in driving inflation. France, for instance, had large price-suppressing fiscal measures and a relatively small contribution of energy to headline inflation shocks.

Monetary policy also played a critical role in defeating inflation. Throughout this period, long-term inflation expectations remained well anchored. This suggests that central banks retained credibility and that this helped prevent wage-price spirals. Global tightening of monetary policy may also have helped bring down global demand and hence energy prices. At the same time, energy shocks and their pass-through, as well as their reversal, account for the bulk of the rise and fall of inflation, without the need for a deep economic slowdown. Even so, in the case of the United States, strong macroeconomic conditions have been a more important contributor to core inflation than in other countries. Since March 2024, when our sample ends, US labor market conditions have further moderated, and this should help inflation return to target.

Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas, the IMF’s economic counsellor and director of the Research Department, contributed to this article, which draws on "Understanding the International Rise and Fall of Inflation Since 2020,” a paper by Dao, Gourinchas, Leigh, and Mishra that is forthcoming in the Journal of Monetary Economics.

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect IMF policy.