A man walking in the Pakistan Stock Exchange building. The pandemic has increased financing needs in Pakistan and other countries across the region. (photo: IMF)

Four Questions About Debt and Financing Risks from COVID-19 in the Middle East and North Africa

April 28, 2021

Across the Middle East, North Africa, Afghanistan, and Pakistan (MENAP), countries responded to the COVID-19 pandemic with unprecedented scale and urgency. While this strong response helped save lives and cushion the economic blow, it also exacerbated existing debt vulnerabilities and led to a surge in financing needs.

Related Links

The IMF’s Regional Economic Outlook Update for the Middle East and Central Asia explores these issues and policies to address them.

Here are four key questions:

- How significant were debt vulnerabilities in MENAP prior to the pandemic and what were the primary concerns? Many countries were already facing high debt. By the end of 2019, one-half of MENAP countries had government debt ratios above 70 percent of GDP and one in four countries faced public gross financing needs above 15 percent of GDP annually.

With limited access to external financing, governments and large state-owned enterprises turned to domestic banks. This expanded banks’ exposure to the public sector in several of MENAP’s emerging markets—ranging from over 20 percent of total banks’ assets in Iraq, Jordan, and Qatar, to above 45 percent in Algeria, Egypt, and Pakistan, and up to 60 percent in Lebanon. By contrast, banks in emerging markets elsewhere had a public sector exposure of 12 percent. - How did the pandemic affect the region’s deficits, debt, and financing strategies? The collapse in economic activity led to losses in fiscal revenues, as

countries increased government spending to mitigate the pandemic’s impact.

As a result, fiscal balances worsened across nearly all countries. Compared

to pre-pandemic expectations, primary deficits in MENAP expanded by an

average of 7.5 percent of GDP in 2020. These higher deficits, combined with

the economic slowdown, resulted in a 7 percentage-point average increase in

debt-to-GDP ratios.

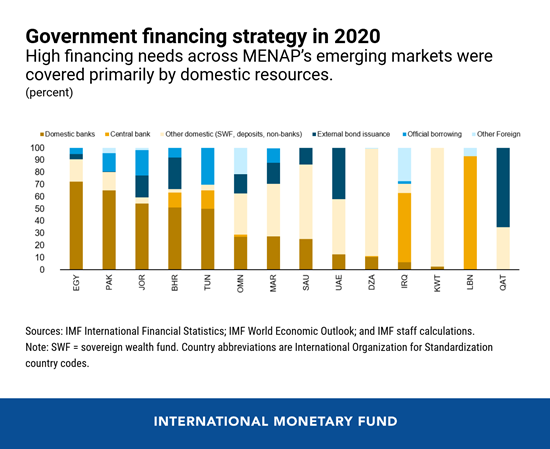

Although one-third of MENAP countries tapped international financial markets—representing 25.5 percent of worldwide emerging market issuances—domestic financing played a critical role, particularly during the first phase of the crisis when international markets were disrupted. For instance, governments in Egypt, Jordan, Pakistan, and Tunisia covered more than 50 percent of their public gross financing needs with domestic bank financing in 2020.

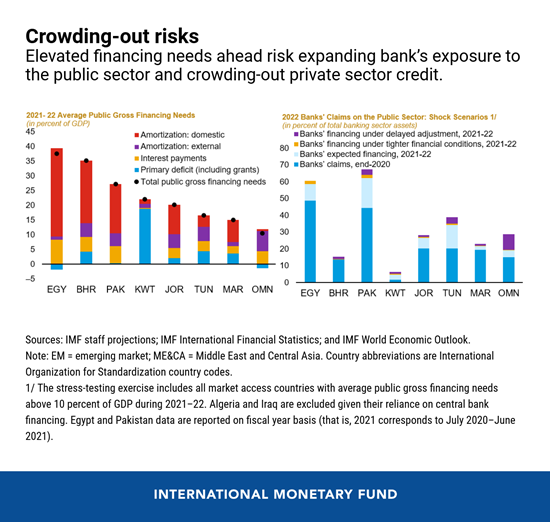

- What challenges will MENAP’s emerging markets face due to higher financing needs ahead? Public gross financing needs are projected to rise to a total of $1,044

billion in 2021–22, from $780 billion in 2018–19. Financing needs during

2021–22 are expected to remain above 15 percent of GDP, on average, in most

MENAP’s emerging markets, albeit with limited needs from external debt

amortization (about 4 percent of GDP).

Since prospects for heavily tapping international markets are limited, banks’ exposure to the state is likely set to accelerate in the years ahead. This could crowd out private sector credit at a time when private financing is critically needed to spur the recovery. Moreover, the Regional Economic Outlook estimates that budgetary needs could be further exacerbated by 3 percent of GDP under a potential shock scenario involving rapid tightening of global financial conditions along with delayed fiscal adjustment due to a protracted recovery. If domestic banks fund these unexpected needs, in addition to the expected financing needed during 2021–22, Egypt, Oman, Pakistan, and Tunisia would absorb an additional 10 to 23 percent of banks’ assets as government debt by the end of 2022. As a result, Egypt and Pakistan’s banks could reach levels of public sector exposure similar to those currently seen in Lebanon.

- What policies can help countries reduce debt vulnerabilities? Countries will need credible and clearly communicated medium-term fiscal

and debt management strategies. These will require careful coordination

among the monetary, fiscal, and financial sector regulatory authorities to

form a common view on the overall absorption capacity of domestic financial

markets.

Countries with limited or no fiscal space will need to initiate growth-friendly consolidation plans as the crisis subsides. In countries with market access, policymakers should work to proactively mitigate rollover and refinancing risks. Engaging in liability management operations (such as extending maturities) can improve terms on existing debt and the medium-term debt profile. In countries where market access is more limited, governments could consider reprofiling their commercial and bilateral debt.

Developing domestic capital markets, gradually broadening the investor base, and expanding banks’ opportunities to diversify their assets, including from further progress on financial inclusion, would help reduce risks from banks’ overexposure to the state. Over the medium term, policymakers could introduce changes to banking regulations to reduce the existing bias of banks’ asset portfolios toward government bonds.

Banks’ excess liquidity in some countries and an underdeveloped institutional investor base in others, together with the lack of a more vibrant private sector, have created incentives for banks to hold government bonds until maturity, hindering domestic debt market liquidity and development.