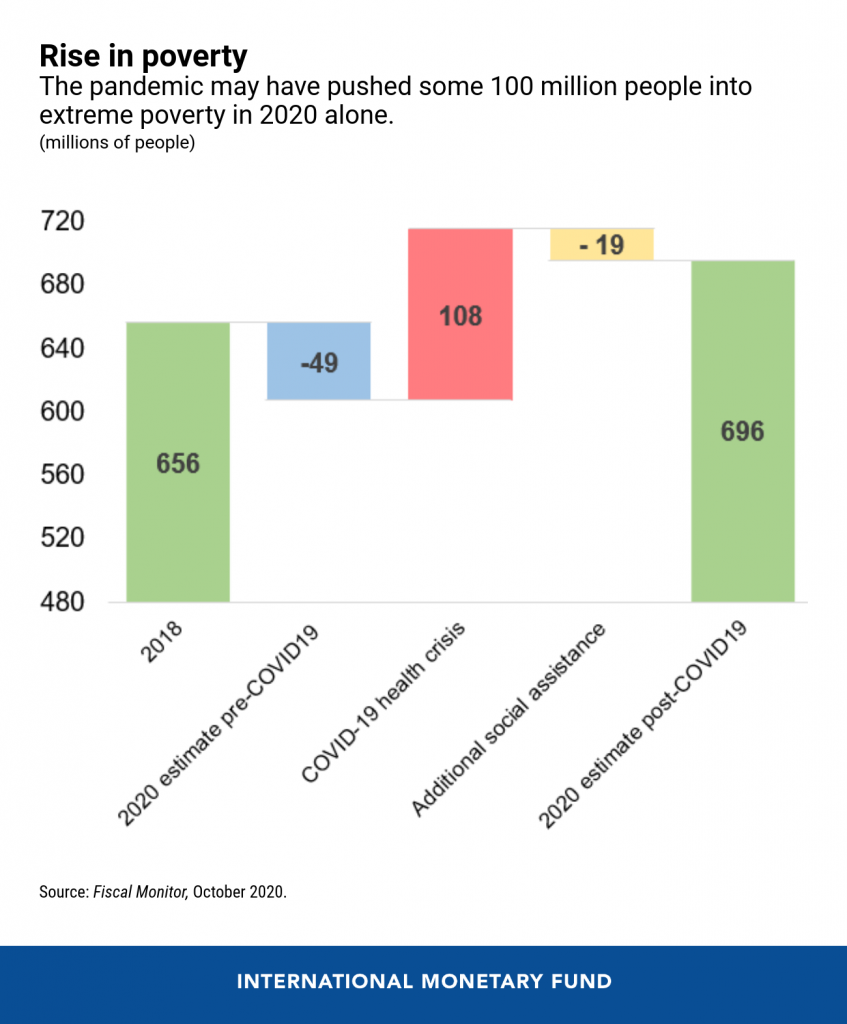

The pandemic’s impact on the world’s poor has been especially harsh. COVID-19 may have pushed about 100 million people into extreme poverty in 2020 alone, while the UN warns that in some regions poverty could rise to levels not seen in 30 years.

The current crisis has derailed progress toward basic development goals, as low-income developing countries must now balance urgent spending to protect lives and livelihoods with longer-term investments in health, education, physical infrastructure, and other essential needs.

In a new study, we propose a framework for developing countries to evaluate policy choices that can raise long-term growth, mobilize more revenue, and attract private investments to help achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Even with ambitious domestic reforms, most low-income developing countries will not be able to raise the necessary resources to finance these goals. They need decisive and extraordinary support from the international community—including private and official donors and international financial institutions.

Major setback

In 2000, global leaders set out to end poverty and create a path to prosperity and opportunity for all. These objectives were anchored by the Millennium Development Goals and 15 years later by the Sustainable Development Goals set out for 2030. The latter represent a shared blueprint for peace and prosperity, for people and the planet, now and into the future. They require significant investments in both human and physical capital.

Until recently, development progressed steadily, albeit unevenly, with measurable success in reducing poverty and child mortality. But even before the pandemic, many countries were not on track to meet the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030. COVID-19 hit the development agenda hard, infecting more than 150 million people and killing over three million. It plunged the world into a severe recession, reversing income convergence trends between low-income developing countries and advanced economies.

The IMF has provided emergency financing of $110 billion to 86 countries, including 52 low-income recipients, since the pandemic started. We have committed $280 billion overall, and our planned general SDR allocation of $650 billion will benefit poor countries without adding to their debt burdens. The World Bank and other development partners have also offered support. But this alone is not enough.

In our paper, we develop a novel macroeconomic tool to help assess development financing strategies, including the financing of the Sustainable Development Goals. We focus on investment in social development and physical capital in five areas at the core of sustainable and inclusive growth—health, education, roads, electricity, and water and sanitation. These key development areas are the largest outlays in most government budgets.

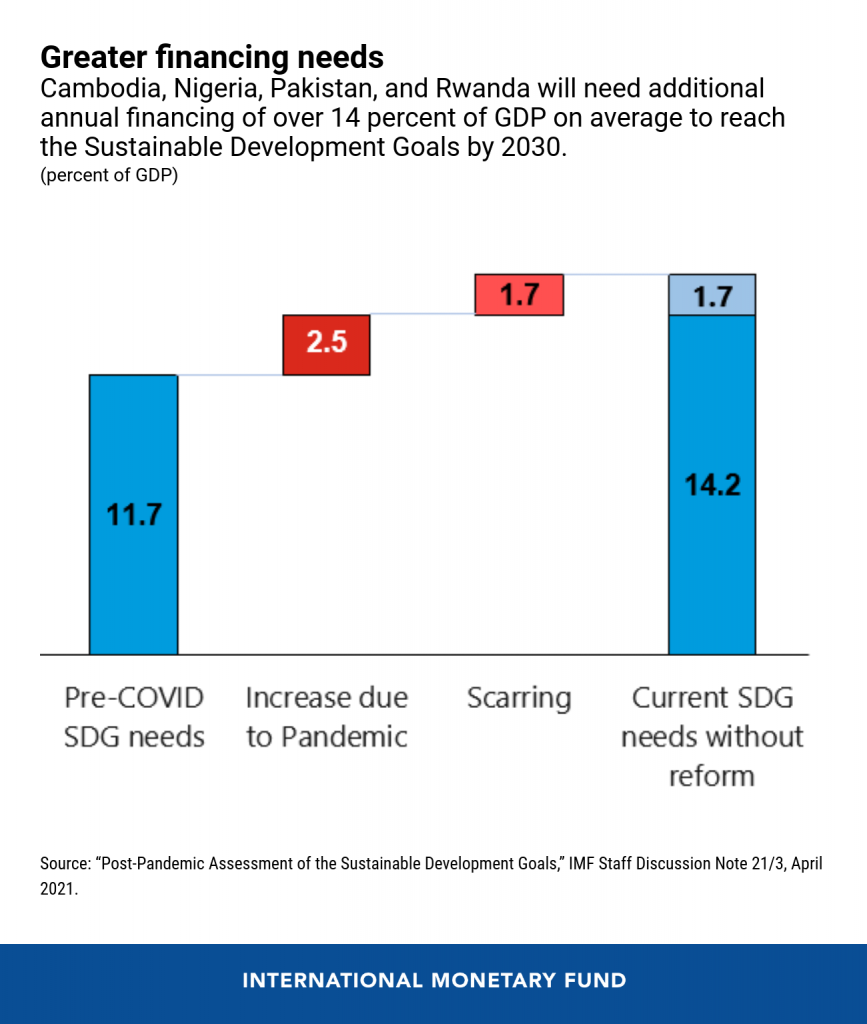

We apply our framework to four countries—Cambodia, Nigeria, Pakistan, and Rwanda. These countries will, on average, need additional annual financing of over 14 percent of GDP to meet the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030, some 2½ percentage points per year above the pre-pandemic level. Put differently, without increasing financing, COVID-19 may have delayed progress toward the Sustainable Development Goals by up to five years in the 4 countries.

The setback could be much larger if the pandemic results in permanent economic scarring. Lockdown measures have significantly slowed economic activity, depriving people of income and preventing children from attending school. We estimate that the long-lasting damage to an economy’s human capital, and hence growth potential, could increase the development financing needs by an additional 1.7 percentage points of GDP per year.

Meeting the challenge

How can countries hope to make meaningful progress toward the Sustainable Development Goals under these new, more difficult circumstances triggered by the pandemic?

It will not be easy. Countries will have to find the right balance between financing development and safeguarding debt sustainability, between long-term development objectives and pressing immediate needs, and between investing in people and upgrading infrastructure. They will have to continue attending to the matter at hand—managing the pandemic. At the same time, however, they will also need to pursue a highly ambitious reform agenda that prioritizes the following:

- Fostering growth, which will start a virtuous circle. It enlarges the pie, resulting in additional resources for development, which in turn further spurs growth. Structural reforms that promote growth—including efforts to enhance macroeconomic stability, institutional quality, transparency, governance, and financial inclusion—are thus essential. Our study highlights how Nigeria and Pakistan’s strong growth enabled them to make significant strides in reducing extreme poverty prior to 2015. Jumpstarting growth, which has since stalled in these populous countries, will be crucial.

- Strengthening the capacity to collect taxes is vital to pay for the basic public services that are necessary to achieve key development objectives. Experience shows that increasing the tax-to-GDP ratio by an average of 5 percentage points over the medium term through comprehensive tax policy and administration reforms is an ambitious but achievable objective for many developing countries. Cambodia has done it: in the 20 years leading up to the pandemic, it increased its tax revenue from less than 10 percent of GDP to around 25 percent of GDP.

- Enhancing the efficiency of spending. About half of the spending on public investment in developing countries is wasted. Improving efficiency through better economic management together with enhanced transparency and governance will allow governments to achieve more with less.

- Catalyzing private investment. Strengthening the institutional framework through better governance and a more robust regulatory environment will help catalyze additional private investment. Rwanda, for example, was able to increase private investment in the water and energy sectors from virtually nothing in 2005–09 to over 1½ percent of GDP per year in 2015–17.

Pursued in tandem, these reforms could generate up to half the resources needed to make substantial progress toward the Sustainable Development Goals. But even with such ambitious reform programs, we estimate that development objectives would be delayed by a decade or more in three of our four case study countries if they were to go it alone.

This is why it is critical for the international community to step up as well. If development partners gradually increase official development aid from the current 0.3 percent to the UN target of 0.7 percent of Gross National Income, many low-income developing countries may well be in a position to meet their development objectives by 2030 or shortly thereafter. Providing such assistance may be a tall order for policymakers in advanced economies, who are likely more focused right now on domestic challenges. But helping development is a worthy investment with potentially high returns for all. In the words of Joseph Stiglitz, the only true and sustainable prosperity is shared prosperity.