中文, Baˈhasa indoneˈsia, 日本語, Português, Русский (pdf)

In the decade since the collapse of US investment bank Lehman Brothers sparked the most severe economic crisis since the Great Depression, regulation and supervision of the financial sector have been strengthened considerably. This has reduced the risk of another crisis, with all its attendant woes—unemployment, foreclosures, bankruptcies. But a new risk has emerged: reform fatigue.

As memories of the crisis fade, financial-market participants, policy makers, and voters are growing weary of calls for new regulations, and some are even demanding a rollback of existing ones. There is good reason to resist these pressures. The reform agenda that aimed to prevent another financial crisis has not yet been fully implemented, and new risks to global financial stability continue to emerge. To complete the agenda and meet new challenges, international cooperation will be vital, according to Chapter 2 of the latest Global Financial Stability Report.

Risk tends to migrate to new, unexpected corners of the financial system.

A safer financial system

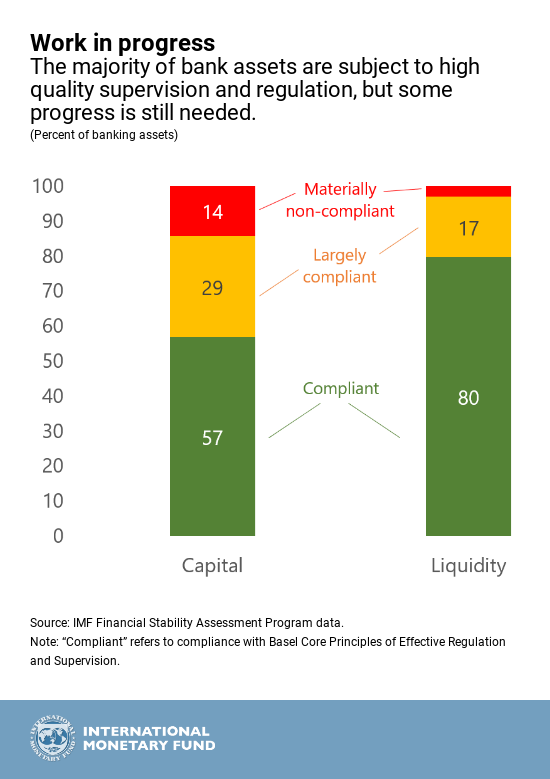

To be sure, the financial system is safer. Banks have thicker and better capital cushions to absorb losses, and they are now better able to convert assets into cash in times of stress. Countries also use stress tests to check the health of the biggest banks and have set up oversight authorities to monitor risks to the financial system. But there is still more work to be done. In particular, implementation of the so-called leverage ratio, which constrains banks’ ability to expand excessively during boom times, should be completed, and supervisors must not weaken oversight of major banks whose failure could pose a threat to the financial system.

Where else should authorities focus their attention?

-

Liquidity . Before the crisis, many financial firms borrowed money for short terms in wholesale markets to fund longer-term assets. When trouble struck, they were unable to roll over the short-term borrowing, forcing them to sell assets at fire-sale prices. In response, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, a global standard-setting body, introduced the so-called Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) and the Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR). Their purpose: to encourage banks to hold more liquid assets as protection against a sudden drop in funding, and to better align the maturities of their assets and liabilities. Most countries have adopted the LCR, but the NSFR is still a work in progress. This work must be completed.

-

Macroprudential regulation. Countries, including India and the United States, have set up authorities to monitor and contain systemic risks. In many places, however, these authorities lack sufficient powers and tools to rein in excessive buildup of leverage and mismatches in non-financial corporations and households. Cross border cooperation in data sharing and systemic risks also should be improved.

-

Shadow banking. Countries have made progress in overseeing and, to a lesser extent, prudentially regulating so-called shadow banks, such as asset-management companies. But work remains to be done, and in many countries, including China and other emerging markets, the rapid growth of shadow banking could pose risks to other areas of the financial system.

-

Bank resolution: During the crisis, costly taxpayer-funded bailouts of large banks, while helping to limit the damage to the financial system, caused a popular backlash. After the crisis, countries adopted measures making it easier to wind down, or resolve, large banks in a way that imposes greater costs on shareholders and limits the use of public money. But there has been less progress on resolution regimes for insurance companies, and cooperating across borders to address the failure of the world’s largest banks is a particular challenge.

Those are some of the remaining gaps in the post-crisis regulatory agenda. But new risks are also emerging, including the threat of destabilizing cyber-attacks on financial firms and exchanges. And new financial technologies, while offering benefits such as faster and cheaper electronic payments, also pose challenges. Regulators must strive to encourage beneficial innovation while safeguarding against risks that could amplify shocks to the financial system. Here again, international cooperation will be vital, because innovative technologies spread quickly across borders.

Above all, regulators must avoid complacency. It’s not possible to reduce the chance of a crisis to zero, nor should we seek to. With ten years of experience in implementing the new reforms, an evaluation of the impact of these on the broader economy is in order. Regulators could then assess whether tradeoffs arise between costs and burdens imposed by new rules and the benefits of greater safety. And they must remember that risk tends to rise during good times, and it migrates to new, unexpected corners of the financial system. They mustn’t get caught fighting the last war.