Typical street scene in Santa Ana, El Salvador. (Photo: iStock)

IMF Survey : Global Economy Faltering from Too Slow Growth for Too Long

April 12, 2016

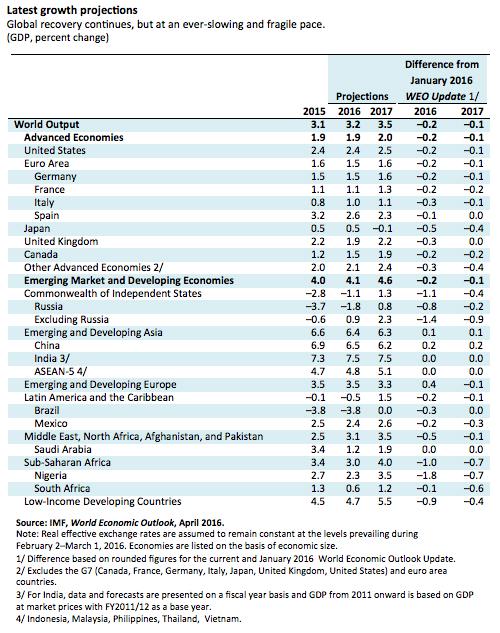

- Global growth forecast at 3.2 percent this year, picking up to 3.5 percent in 2017

- Financial risks prominent, together with geopolitical shocks, political discord

- Need for three-pronged approach spanning structural, fiscal, monetary measures

Global growth continues, but at a sluggish pace that leaves the world economy more exposed to risks, says the IMF’s latest World Economic Outlook (WEO).

The world outlook is clouded by persistent weak growth, limited job growth, still high debt, and higher economic and noneconomic risks (photo: Demos Vrublevski)

WORLD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK

The WEO forecasts global growth at 3.2 percent in 2016 and 3.5 percent in 2017, a downward revision of 0.2 percent and 0.1 percent, respectively, compared with the January 2016 Update (see table).

In a recent speech, IMF Managing Director Christine Lagarde warned that the recovery remains too slow, too fragile, with the risk that persistent low growth can have damaging effects on the social and political fabric of many countries.

“Lower growth means less room for error,” said Maurice Obstfeld, IMF Economic Counsellor and Director of Research. “Persistent slow growth has scarring effects that themselves reduce potential output and with it, demand and investment,” he added.

The current diminished outlook calls for an immediate, proactive response, Obstfeld noted. To support global growth, he emphasized, there is a need for a more potent policy mix—a three-pronged policy approach based on structural, fiscal, and monetary policies.

“If national policymakers were to clearly recognize the risks they jointly face and act together to prepare for them, the positive effects on global confidence could be substantial,” Obstfeld added.

Moderate recovery in advanced economies

Growth in advanced economies is projected to remain modest at about 2 percent, according to the WEO. The recovery is hampered by weak demand, partly held down by unresolved crisis legacies, as well as unfavorable demographics and low productivity growth.

In the United States, expected growth this year is flat at 2.4 percent, with a modest uptick in 2017. Domestic demand will be supported by improving government finances and a stronger housing market that help offset the drag on net exports coming from a strong dollar and weaker manufacturing.

In the euro area, low investment, high unemployment, and weak balance sheets weigh on growth, which will remain modest at 1.5 percent this year and 1.6 percent next year.

In Japan, both growth and inflation are weaker than expected, reflecting in particular a sharp fall in private consumption. Growth is projected to remain at 0.5 percent in 2016 before turning slightly negative to -0.1 percent in 2017, as the scheduled increase in the consumption tax rate goes into effect.

Emerging and developing economies slowing further

While emerging markets and developing economies will still account for the lion’s share of world growth in 2016, prospects across countries remain uneven and generally weaker than over the past two decades.

The WEO projects their growth rate to increase only modestly—relative to 2015—to 4.1 percent this year and 4.6 percent next year.

This forecast reflects a variety of factors:

• Slowing growth in oil exporters, with oil price decline, and still weak outlook for non-oil commodity exporters, including in Latin America.

• The modest slowdown in China, where growth continues to shift away from manufacturing and investment to services and consumption.

• Deep recessions in Brazil and Russia, and weak growth in some Latin America and Middle East countries, particularly those hit hard by the oil price decline and intensifying conflicts and security risks.

• Diminished growth prospects in many African and low-income nations due to the unfavorable global environment.

On the positive side, India remains a bright spot—with strong growth and rising real incomes. The ASEAN-5 economies—Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam—are also performing well. And Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean are beneficiaries of the U.S. recovery and, in most cases, lower oil prices.

Risks are on the rise

In the current environment of weak growth, risks to the outlook are now more pronounced.

These include:

• A return of financial turmoil, impairing confidence. For instance, an additional bout of exchange rate depreciations in emerging market economies could further worsen corporate balance sheets, and a sharp decline in capital inflows could force a rapid compression of domestic demand.

• A protracted period of low oil prices could further destabilize the outlook for oil-exporting countries.

• A sharper slowdown in China than currently projected could have strong international spillovers through trade, commodity prices, and confidence, and lead to a more generalized slowdown in the global economy.

• Shocks of a noneconomic origin—related to geopolitical conflicts, political discord, terrorism, refugee flows, or global epidemics—loom over some countries and regions and, if left unchecked, could have significant spillovers on global economic activity.

On the upside, the recent decline in oil prices may boost demand in oil-importing countries more strongly than currently envisaged, including through consumers’ possible perception that prices will remain lower for longer.

Raising growth still a priority

More aggressive policy actions to lift demand and supply potential could foster stronger growth in both the short and longer term.

The WEO emphasizes a three-pronged approach of mutually reinforcing policy levers. These include (1) structural reforms, (2) fiscal support, with growth-friendly composition of revenue and spending, and fiscal stimulus where there is a need and where fiscal space allows, and (3) monetary policy measures.

There is strong need and scope for further structural reforms. Analytical work featured in the WEO finds that labor and product market reforms in advanced economies can give a strong boost to growth prospects over the medium to long term. Carefully prioritizing and sequencing reforms is essential to boost their short-term effects.

Product market reforms—which aim to boost competition among firms and make it easier to start a business or attract investment—should be implemented forcefully, as they boost output even under weak macroeconomic conditions and without weighing on public finances. Where possible, narrowing unemployment benefits and easing job protection should be accompanied by other policies to offset their short-term cost on vulnerable groups.

Reforms that are coupled with fiscal support will be the most valuable at this juncture, including reducing inefficient taxes on labor and increasing public spending on research and development and active labor market policies (reforms aimed at getting the unemployed back into work, such as job training programs).

In many advanced economies, accommodative monetary policy remains essential to support economic activity and lift inflation expectations. In many emerging market and developing economies, monetary policy must grapple with the impact of weaker currencies on inflation and private sector balance sheets. Exchange rate flexibility, where feasible, should be used to cushion the impact of terms of trade shocks.

Finally, further financial sector strengthening is essential, including to create a context in which monetary, fiscal, and structural policies can be most effective.

The WEO warns that policymakers also need to make contingency plans and design collective measures for a possible future in case downside risks materialize. Cooperation to enhance the global financial safety net and global regulatory regime is also central to a resilient international and financial system.