Having fewer workers outside the formal economy can support sustainable development

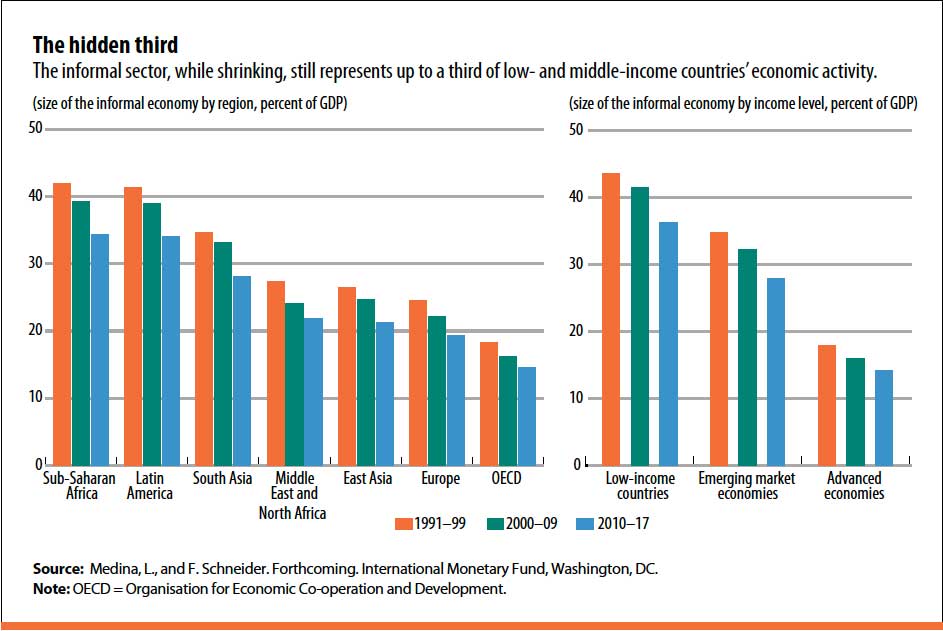

The informal economy, comprising activities that have market value and would add to tax revenue and GDP if they were recorded, is a globally widespread phenomenon. According to the International Labour Organization, about 2 billion workers, or 60 percent of the world’s employed population ages 15 and older, spend at least part of their time in the informal sector. The size of the informal sector slowly decreases as economies develop, but with wide variations across regions and countries. Today, the informal sector still accounts for about a third of low- and middle-income countries’ economic activity—15 percent in advanced economies (see chart).

Informality covers a wide range of situations within and across countries, and it arises for a number of reasons.

On the one hand, individuals and firms may choose to remain outside the formal economy to avoid taxes and social contributions or compliance with standards and licensing requirements. This relates to the common but misconceived view that informality is caused mainly by firms and individuals “cheating” to avoid paying taxes. On the other hand, individuals may rely on informal activities as a safety net: they may lack the education and skills for formal employment or be too poor to access public and financial services. A forthcoming book compiling recent research by IMF staff and academic researchers aims to shed new light on this topic by looking in more detail at measuring informality, analyzing its drivers and economic consequences, and discussing possible policy responses.

The high incidence and persistence of informal labor, particularly in emerging market and developing economies, is increasingly recognized as an obstacle to sustainable development. Informal firms do not contribute to the tax base and tend to remain small, with low productivity and limited access to finance. As a result, economic growth in regions or countries with large informal sectors remains below potential. Informal workers are more likely to be poor than workers in the formal sector, both because they lack formal contracts and social protection and because they tend to be less educated.

The prevalence of informal work is also associated with high inequality: workers with similar skills tend to earn less in the informal sector than their formal sector peers, and the wage gap between formal and informal workers is higher at lower skill levels. This explains why the large decline in informality in Latin America observed over the past 20 years was associated with significant reductions in inequality.

Informal work is similarly linked with gender inequality. In two out of three low- and lower-middle-income countries, women are more likely than men not only to be in informal employment, but also to be in the most precarious and low-paying categories of informal employment.

Addressing informality is thus essential and urgent to support inclusive economic development and reduce poverty worldwide. The COVID-19 pandemic has only reinforced this sense of urgency: its crushing impact on informal activities worldwide has highlighted the need for governments to provide a lifeline for large segments of the population not covered (or not well covered) by existing social protection programs.

Designing effective policies to address informality is, however, complicated by its multiple causes and forms, both across and within countries. Informality is a response to a set of country-specific characteristics and institutions, and there is no one-size-fits-all solution. Extensive research and policy experiments in both developing and advanced economies nonetheless point to a common set of guiding principles for policy design. Four types of policies have proved effective:

- Improving access to and quality of education is probably the single most powerful way to lower informality. Education reforms aimed both at enhancing equality of access and ensuring that students remain in school until the end of the secondary cycle (and ample technical and vocational training opportunities) are particularly important.

- Tax system design should avoid inadvertently increasing incentives for individuals and firms to remain in the informal sector. It is generally recognized that simpler value-added and corporate tax systems (with no or minimal exemptions and loopholes) with lower rates, as well as low payroll taxes, help reduce informality. Supportive social protection systems, including progressive income taxes and protection for the poorest, help address distributional aspects.

- Policies to enhance financial inclusion by promoting expanded access to formal (or bank-based) financial services can help lower informality. Lack of access to finance is a key constraint for informal firms and entrepreneurs, stifling productivity and the growth of their businesses. Countries where access to finance is greater tend to grow faster and have lower income inequality.

- A range of structural policies can help increase incentives and lower the cost of formalization. Labor market regulations can be simplified to ensure greater flexibility and facilitate informal workers’ entry into formal employment. Competition policy can boost entry of small firms in some sectors by eliminating monopolies. Elimination of excessive regulations and bureaucratic requirements also helps. Digital platforms, including government-to-person mobile transfers, can contribute to inclusive growth by bringing financial accounts to the unbanked, empowering women financially, and helping small and medium-sized enterprises grow within the formal sector.

Informality critically affects how fast economies can grow, develop, and provide decent economic opportunities for their populations. Sustainable development requires a reduction in informality over time, but this process will inevitably be gradual because the informal sector is currently the only viable income source for billions of people. Informality is best tackled by steady reforms—such as investment in education—and policies that address its underlying causes. Attacks on the sector motivated by the view that it is generally operating illegally and evading taxes are not the answer.

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect IMF policy.