Central Bank Independence: Why It’s Needed and How to Protect It

June 14, 2024

Good afternoon Mr. Governor, Members of the Board, esteemed colleagues.

Today I will be speaking about key developments in central banking—most notably, on the concept of central bank independence, and what central banks can do to safeguard independence and ensure policy credibility.

First, it is important to set the stage.

We must recognize that many central banks are under tremendous pressure. Post-pandemic inflation levels required central bankers to tighten monetary policy. However, this created significant political pushback as it causes growth to slow, unemployment to rise, and the fiscal position to deteriorate. Additionally, financial stability measures taken by central banks, including through emergency liquidity assistance and bank resolution, have led to further expanded balance sheets and come with increased financial risk for central banks.

To complicate things further, price stability is not the only game in town anymore, and some central banks have objectives related to financial integrity, financial inclusion, consumer protection, fintech, and even climate change.

Moreover, financial institutions increasingly demand that central banks and financial supervisors live up to the same standards that they roll out onto the financial sector, especially when it comes to standards on governance, risk management, and transparency.

Central bank stakeholders, including parliament and market participants, have increased expectations of what the central bank can and should do. But, with a more challenging environment in terms of economic growth and inflation, as well as expanded mandates, stakeholders may increasingly scrutinize the central banks’ policies and operations and question the validity of independence.

Central banks across the world are often criticized for supposedly misusing their independence. But there are two sides to that coin:

In the US, there have been calls for stronger oversight of the Federal Reserve; yet the IMF notes that the Fed, in its fight to tame inflation, needs to be steadfast in its monetary policy approach, all the while ensuring careful communication as well.

In Europe, similarly, the ECB was critiqued for its use of quantitative easing and lack of accountability. Yet the IMF notes that it is essential that central banks ensure inflation stays with comfort zones—which requires a longer time horizon.

And in the UK, a recent report called for more oversight of the Bank of England—with the IMF noting that this creates opportunities for the Bank to strengthen its monetary policy communication.

So, with the increased calls for more oversight, we must ask why is central bank independence still necessary?

The IMF’s Managing Director said it clearly earlier this year, when she noted that “independence is critical to winning the fights against inflation and achieving stable long-term economic growth.” On this point the data is clear: higher central bank independence is associated with lower inflation.

But, the Managing Director also highlighted that policymakers risk facing pressure due to political forces questioning central bank independence. This holds for advanced, emerging and developing economies alike, and especially in times of general elections.

In a recent White House blog, the Council of Economic Advisers stressed the need for central bank independence across political cycles. Expectations of inflation in the US have stayed anchored around 2 percent, even though CPI inflation shot up drastically in the aftermath of the pandemic. The White House noted that this is predominantly due to the independence of the Federal Reserve, which allows its policies to remain credible and make it effective in combatting high inflation.

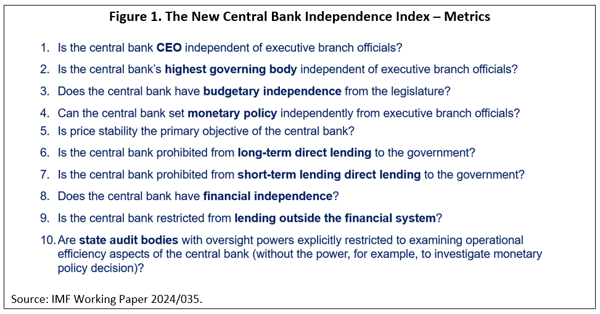

Together with my two co-authors, Lev Menand of Columbia University, and Ashraf Khan of the IMF, we developed a new global index for central bank independence, based on the ten metrics noted in Figure 1, and aimed at helping central banks and policy makers strengthen central bank independence.

This is the first new central bank independence index in 30 years. And even though it builds on existing indices, it includes new variables such as financial and budgetary independence, board composition, and the role of state audit bodies. Interestingly, the variable of financial independence was rated by central bankers as the most critical component of central bank independence. Whereas the prohibition of short-term lending to government was rated as comparatively less important.

The index uses data from critical IMF databases to ensure a solid foundation for country scoring. And, the application and weighting of these metrics is based on an extensive survey conducted among 87 central banks worldwide, ensuring that we have an independence index developed by central bankers for central bankers.

Overall, our new index is more conservative in scoring central banks, compared to the existing indices that score advanced economies significantly higher than emerging and developing economies.

Lastly, our index is the first index that correlates positively with inflation-targeting central banks—showcasing that independence is significantly stronger in the countries where inflation targets are more firmly entrenched in central bank operations.

Where do we often see weak points in central bank independence?

Independence is sometimes lacking at the level of the central bank governor and the Board, but there are also shortcomings in budget and financial independence, monetary policy independence, as well as in the prohibition of short- and long-term lending to government or the prohibition of lending outside the financial system.

As we have seen in the survey results, financial independence is rated as the most important variable among central bankers. This means that improvements there can offer a bigger “bang for the buck” and result in markedly strengthened independence. At the same time, the process of law reform to strengthen financial independence can be quite a delicate exercise. However, there are some specific IMF tools that could help, and that do not require embarking on a legislative reform path.

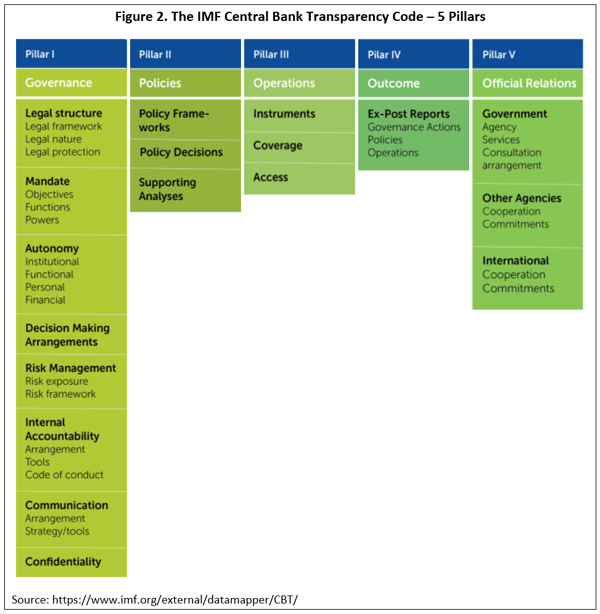

The first tool is the IMF Central Bank Transparency Code, or “CBT,” which was published in 2020. We developed the CBT in part because of increased pressure on central banks and the calls of parliaments and other stakeholders for central bank transparency.

It has five pillars, as shown in Figure 2, covering transparency over governance of the central bank, its policies, its operations, and outcomes of those operations, as well as official relations of the central bank with its key stakeholders. It is designed to be applicable to any central bank, under any set of circumstances.

Of course, the focus of the CBT is not full transparency. Instead, the Code makes it clear that there are legitimate needs for confidentiality—for instance when it comes to foreign exchange interventions, or other sensitive or personal data.

The benefits of a CBT Review for central banks are four-fold: First, it helps improve the central bank’s transparency practices and the communication framework, leading to policy credibility. Second, it will strengthen relations with stakeholders such as parliament, market participants, and the public at large. Third, it will facilitate peer-learning among central banks. Finally, it can help in other engagements with the IMF, for instance in the context of a financial sector assessment. Central banks that have recently undergone a CBT Review include the central banks of Canada, Chile, Oman, and South Africa.

In fact, in all the recently completed CBT Reviews, the central banks involved used the CBT Review to strengthen their transparency, engage more closely with their stakeholders, and thereby enhance their accountability and policy credibility.

The Bank of Canada, for instance, published for the first time its internal deliberations after each policy rate announcement. The Bank of Chile published a detailed roadmap of how additional transparency measures could be implemented, and the Governor presented these to parliament. And, the National Bank of North Macedonia similarly presented CBT findings to the Ministry and parliament, with the Governor highlighting how the central bank’s independence was used to conduct effective policies going beyond political cycles.

A second tool offered by the IMF is central bank balance sheet stress testing, which is intended to help central banks assess their financial independence. This is particularly relevant for central banks in advanced economies where balance sheets were expanded in the wake of the pandemic due to significant quantitative easing and asset purchasing programs.

However, even for markets that did not engage in quantitative easing, but where central banks have large foreign exchange portfolios due to their focus on stable exchange rates, central banks are exposed to interest rate and duration risk on their foreign exchange securities. Both of these risks are often not properly accounted for in central bank capital policies.

Of course, emerging market central banks also remain exposed to foreign exchange losses on the entire portfolio solely emanating from changes in the exchange rate. This is important for governments as well: a deteriorating central bank balance sheet would negatively affect profit distribution—ultimately creating fiscal risks, including through the possibility of having to recapitalize the central bank.

The IMF central bank balance sheet tool therefore combines a core modelling framework with stress testing of various extreme, but plausible scenarios. This leads to granular projections of the state of the balance sheet and the effects on the central bank’s capital over time, serving to inform decision making by the central bank board, and as a foundation for discussions with government.

Finally, a central bank operational efficiency review is a third tool that central banks can use to enhance their independence and policy credibility.

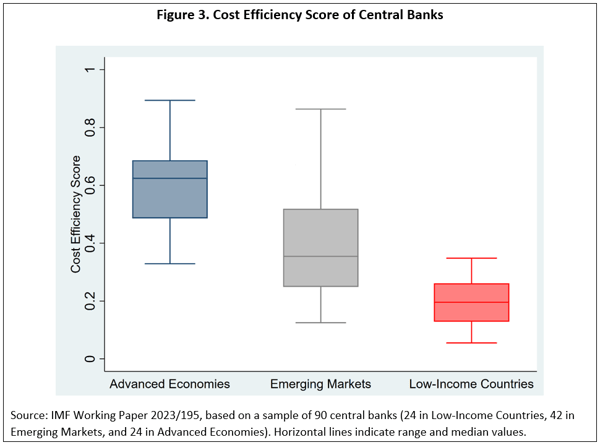

Emerging market central banks have significantly higher operational costs, and are significantly less efficient, than central banks in advanced economies, as depicted by the cost efficiency scores in Figure 3. As part of the review, central bank cost efficiency may be calculated, whereby policy-related costs are left out—as these are a necessity, but other costs related to staffing, procurement, cash currency management, subsidiaries, and other logistics costs such as those relating to building maintenance, are benchmarked against international best practices, as well as against other domestic agencies and central banks in the region. This will help the central bank Board to make well-informed decisions regarding operational costs, as well as explain the decisions to key stakeholders, and thereby strengthen independence.

In summary, while many central banks worldwide are under pressure, it remains clear that independence pays off in the long run. For many central banks, there is room to improve independence, and the IMF offers tailored tools that are used by central banks worldwide to strengthen independence, and ultimately policy credibility.

IMF Communications Department

MEDIA RELATIONS

PRESS OFFICER:

Phone: +1 202 623-7100Email: MEDIA@IMF.org