Crisis Amplifier? How to Prevent AI from Worsening the Next Economic Downturn

May 30, 2024

As prepared for delivery

Good morning. It is an honor to join you here at the AI for Good Global Summit.

We are hearing about some of the extraordinary ways Generative Artificial Intelligence could benefit our societies, including helping us live healthier lives and accelerating scientific breakthroughs. Many experts also believe the technology could provide significant economic benefits, for example by providing a serious boost to productivity. This could help lift the global economy at a time when the growth outlook for the medium term is the weakest in decades.

This said, many also agree that AI’s promise comes with considerable uncertainty and significant risks. To date, most warnings have focused on security, privacy, misinformation, and ethical concerns.

Taking an economic perspective, I would like to highlight a different sort of AI-related risk, one that has received much less attention. That is the risk that AI could exacerbate economic crises.

The world economy will see another downturn—that much is certain. Today I will describe how the widespread use of AI could turn an ordinary downturn into a deep and prolonged economic crisis by causing large-scale disruptions in labor markets, in financial markets, and in supply chains. I will also discuss what policy actions—taken now—can help mitigate some of these downside risks.

The AI Crisis

Let me describe how AI could worsen the next downturn, starting with labor markets. The experience with previous waves of automation offers a warning here. During good times, firms are often flush with profits. They can afford to invest in automation and hold on to workers, even if the value-added of those workers declines. However, in a downturn, these firms simply let go of workers to cut costs. Therefore, the extent to which automation could replace humans only becomes fully visible during or immediately after a downturn.

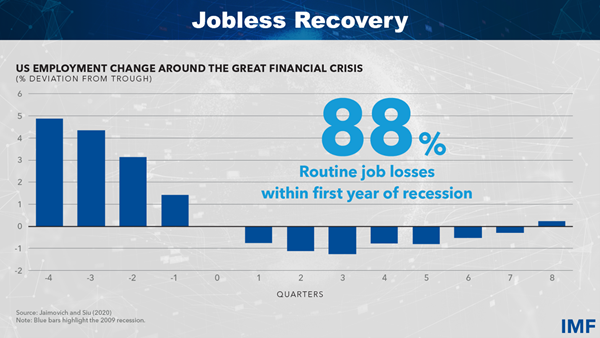

Research by Jaimovic and Siu shows that since the mid-1980s nearly 90 percent of automation related job losses in the U.S. have occurred in the first year of recessions. Take the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis. Rather than rehiring workers after the slump, many firms automated their operations—leading to the most severe "jobless recovery” ever seen in the US and Western Europe, driven almost entirely by the loss of routine jobs. This led to many disillusioned former workers leaving the labor market altogether.

AI threatens to accentuate this dynamic.

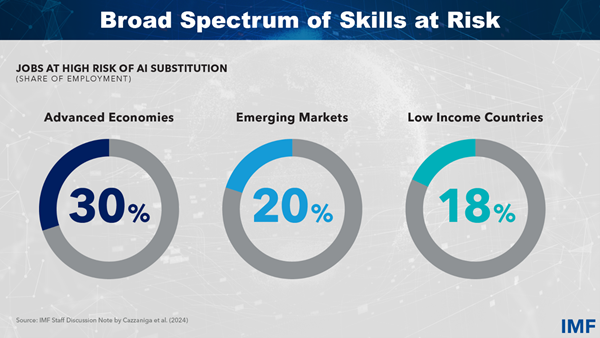

In the next downturn, AI is likely to threaten a wider range of jobs than in past cycles, including higher-skilled cognitive jobs. An estimated 30 percent of jobs in advanced economies are at risk of being replaced by AI. That figure is 20 percent for emerging markets and 18 percent for low-income countries.

In other words, the pool of potentially replaceable workers in future downturns will be bigger than anything we’ve seen before. The result could be unprecedented job losses.

That could also lead to unprecedented numbers of long-term unemployed, because many of the displaced workers will lack the requisite skills in an economy where AI is increasingly prevalent.

Such a sharp spike in unemployment would be a major shock to the financial system, as record numbers of unemployed workers could struggle to repay their debts. However, in this new AI-adapted reality, that would be only part of the disruption to the financial system.

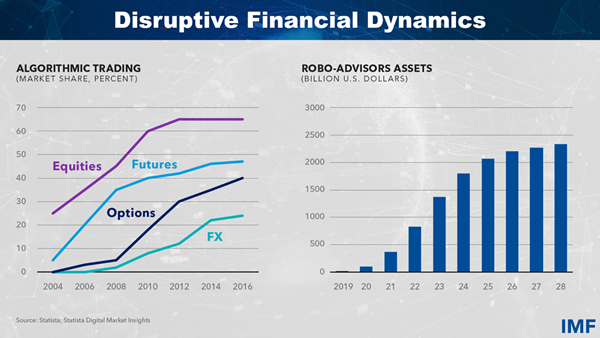

The financial services industry has relied heavily on algorithmic trading since before the recent AI boom. The industry is now rapidly replacing older models with vastly more complex ones that can learn on their own. The inner workings of such models can be difficult even for experts to understand. AI is also growing briskly in client-facing investment businesses, as assets managed by automated robo-advisers, for example, are projected to grow to $2.3 trillion in 2028.

In normal times, these are positive developments. With its ability to harness vast amounts of information to make predictions, AI can help improve the allocation of resources and enhance financial inclusion. In a recent survey of investors, 60 percent anticipated that the use of AI in capital market activities will improve market efficiency over the next 3 years.

However, there are also dark sides to AI-powered investment decisions. In a future downturn characterized by unfamiliar patterns—including unfamiliar patterns of job losses—AI systems could struggle to respond. This is because AI has been shown to perform poorly when faced with novel events—that is events that differ markedly from the data they have been trained on. As a result, they might quickly and simultaneously become overly conservative and rebalance portfolios toward safe assets. The models’ decision to leave other assets will then be rewarded as their prices fall, and a self-confirming spiral of fire-sales and collapsing asset prices across different financial markets could ensue. The “black box” nature of AI would make managing such an event particularly challenging.

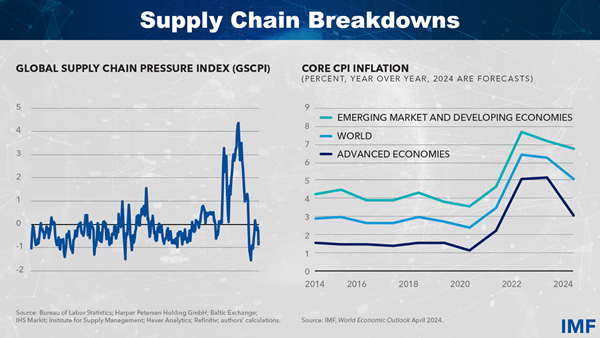

Generative AI could also make a downturn much worse through its impact on global supply chains. The user-friendly features of newer AI models could encourage widespread adoption by companies who would then come to rely on AI predictions for their production decisions. Here again, as in financial markets, in normal times this could bestow numerous benefits, including helping to raise productivity. But in a future downturn, AI algorithms trained on stale information could trigger a series of forecasting errors, creating more rapid swings in production and inventories. This could cause crippling delays and shortages of critical supplies across the global economy.

The recent Covid-19 crisis is a reminder of how costly supply chain disruptions can be for society, including through its impact on prices and living costs.

Taken together, these forms of risks could turn a regular downturn into an AI-amplified economic and financial crisis and present immense challenges for policymakers.

And if this AI crisis were to strike in the next few years, it would be hitting countries at a time when they are already dealing with high debt and low growth, seriously constraining their ability to support workers and firms.

Policy Advice

Let me turn to discussing what policy actions can be taken now to prevent such a crisis. I do so while recognizing the tremendous uncertainty around how any crisis might unfold, and the importance of ensuring that policy actions to attenuate risks do not impair the promise of AI to benefit society. That said, I will describe three actions that can help.

First, we should make sure tax systems do not inefficiently favor automation over people.

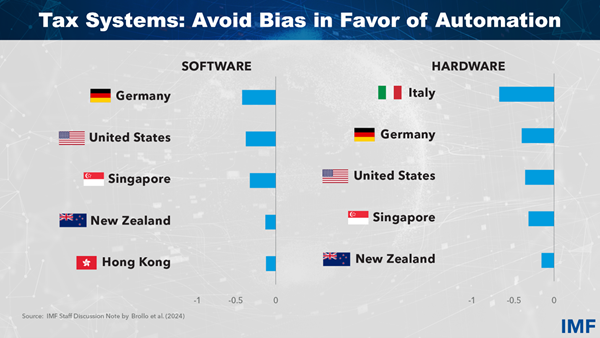

New research by the IMF shows that the tax systems of several countries—including Germany, the United States, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Singapore, and Hong Kong SAR—tend to favor automation. That is, the marginal effective tax rates on software and hardware that have been shown to be labor substituting are lower than on those that tend to complement workers.

This could be justified if the social returns from automation were sufficiently high. Given the economic risks I have laid out, including of substantial and prolonged job market disruptions, it’s questionable whether the returns would be high enough.

To be clear, I am not calling for a special tax on AI—an idea that is increasingly being discussed. Rather, this is a call to reconsider existing corporate tax incentives that may be making AI ‘special’ and encouraging labor substituting investments.

Second, we should take measures to help workers cope with the impacts of AI.

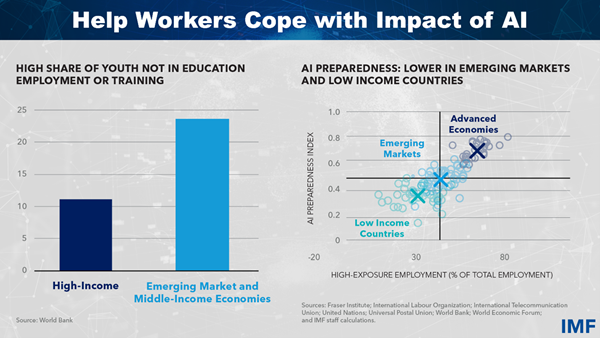

To protect workers from AI labor market disruptions, heavier investments in education and training are essential.

This is especially a priority in emerging-market and developing economies. Almost a quarter of young people in emerging market and middle-income countries are not in employment, education, or training. These young people are exceptionally ill-prepared for rapid technological changes to jobs. According to our AI Preparedness Index, emerging markets and low-income countries are less prepared than advanced economies for this technological shift. Increasing investments in education, digital competencies, and digital infrastructure in such countries are priorities.

Other countries are further ahead in this regard. For example, Singapore offers unconditional grants to all adults for training throughout their working lives.

But such upskilling, though necessary, will not be sufficient to prepare workers for AI’s potentially destabilizing effects. We will also need to protect them by adapting social safety nets to a world where AI could create prolonged job losses.

Forthcoming research by the IMF shows that more generous provision of unemployment insurance can help workers adapt to job market changes. For example, it may reduce the impact of automation-related wage declines, by giving unemployed workers more time to find the right new job. Our research also finds that most countries have scope to broaden the coverage and generosity of unemployment insurance, to improve the portability of entitlements, and to consider different forms of wage insurance.

Third, we should adopt measures to lower financial and supply-chain amplification risks.

To mitigate the threat of an AI-amplified event, financial regulators will need to enhance both supervision and regulation. To do so, regulators will themselves need upskilling to help them understand AI-related risks.

Disclosures by financial institutions and securities issuers may need to be strengthened, to provide visibility on how they use AI, on the source of their AI models, and on their circuit breakers to reduce herding and distress sales.

With growing reliance on AI decision-making, both financial and non-financial companies may need to stress test their AI models against “events like no other” and establish sufficient human oversight to prevent cascading breakdowns.

This list of policy measures might sound daunting. But, as a reminder of AI’s enormous promise, the technology can itself help us undertake many of these measures. Our research shows that AI can help in upskilling labor, for example, especially where teachers are scarce.

Also, public finances can benefit from AI tools that improve tax compliance and widen the tax base. This could lead to an increase in revenues equivalent to as much as 3 percentage points of GDP.

AI can also help better target social assistance. And when it comes to financial supervision, AI tools can contribute through better monitoring and early detection of vulnerabilities and improved risk assessments.

The more that AI research can do to improve the performance of AI models in the face of novel events, the lower will be the risks to financial and supply chain stability.

To be clear: the approach I am advocating would represent a significant shift. Most international efforts to mitigate AI risk are currently directed toward concerns around security, privacy, ethics, and disinformation—and those efforts are important. But we also need a serious international effort to AI-proof the economy.

Policymakers should start that effort by closely tracking how AI is being developed and adopted. They also need to create and analyze a wide range of potential scenarios on how AI might impact economies– an exercise that will require rigorous economic analysis of AI’s potential implications for variables including employment, productivity, and financial stability.

This exercise will require significant investments. But unless policymakers understand how AI impacts the economy, they could be “flying blind” in the next recession.

Let me close by again underlining that I am outlining a significant risk, not making a prediction. As our research demonstrates, there is a lot that policymakers can do to mitigate the threat of an AI amplified economic crisis—while at the same time harnessing the technology’s enormous potential for good.

AI has the power to change our lives and the global economy. We have the power to shape that change for the better.

IMF Communications Department

MEDIA RELATIONS

PRESS OFFICER: Rahim Kanani

Phone: +1 202 623-7100Email: MEDIA@IMF.org