Financing CESEE’s Growth Ambition

May 17, 2024

As prepared for delivery

Thank you, Governor Vasle, for your opening remarks and for hosting this joint Bank of Slovenia – IMF conference in lovely Portorož.

Europe withstood the test of the twin crises. Despite the pandemic in 2020 and the energy shock sparked by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, unemployment is at record lows; banks are sound; and we at the IMF project growth to recover and inflation to go back to targets.

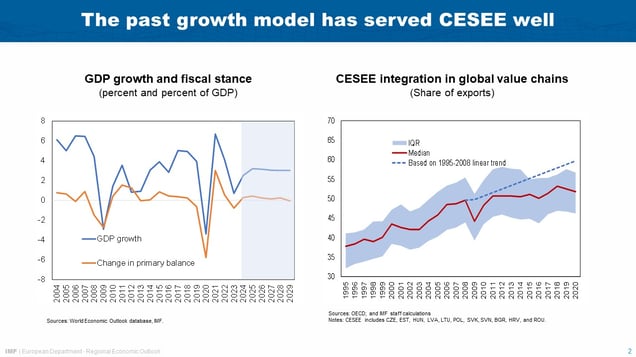

In CESEE this resilience comes on the back of two decades of robust growth.

Growth that was based on integration into Europe’s value chains often financed by FDI. A model that has paid off. Over the last two decades, real economic growth averaged 4 percent.

A sophisticated financial sector was not needed. Bank finance dominated, complemented by funding out of own resources, and foreign direct investment.

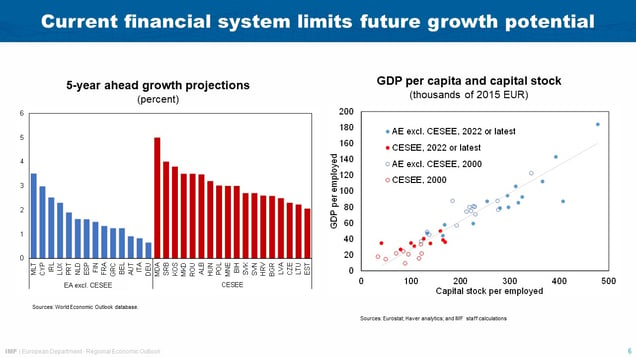

But there are two important caveats. One is that investment has generally been too low to close the capital stock gap with other advanced economies. The other is that the world has changed: the model of the past will not be fit for the challenges of the future.

I want to spend the next minutes outlining what a new growth model could be and what financial system is needed to support it.

So let us look at where we are and what has changed.

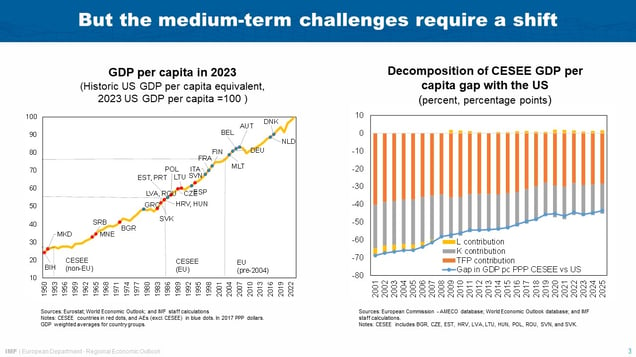

Despite CESEE’s progress, convergence to higher income levels has slowed and the gap to the global frontier, the US, remains large. Those not part of the EU have the income per capita of the US of the mid 1950s when the wall dividing East and West Berlin had not even been built.

Those in CESEE who are part of the EU have the income per capita of the US of 1986, shortly before the Berlin wall fell, almost 40 years ago.

Put differently, the income per capita gap to the US amounts to 45 percent in 2023.

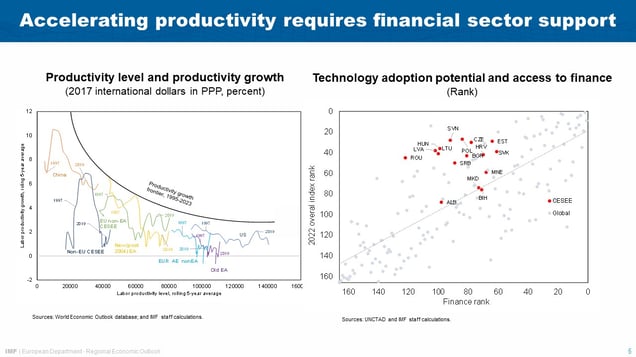

CESEE’s income gap to the US is about capital and technology. Two third of the gap is total-factor productivity and the remainder reflects the lower capital stock.

And this is precisely where the old growth model has started to fail. TFP growth is slowing. And the capital stock gap stopped narrowing.

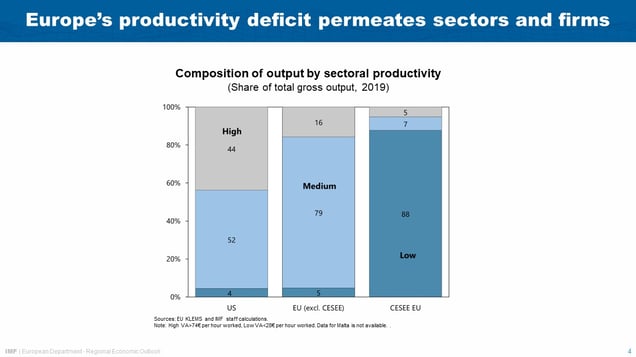

The productivity deficit extends across sectors. The share of CESEE’s high productivity sectors in total output (at 5 percent) is about a third of the rest of the EU. Both regions are far behind the United States (44 percent). Instead, the share of low productivity in CESEE is much larger than elsewhere.

To enhance productivity, CESEE requires more or larger firms closer to the productivity frontier. This means investing in technologies to enable low-productivity firms to catch up, developing new technologies to elevate medium-productivity firms to become high performers, and nurturing new, high productivity firms to grow.

There are also new headwinds:

First, a weaker global medium-term growth outlook—as described in our April World Economic Outlook—implies lower foreign demand. This does not bode well for FDI prospects, which already declined post GFC.

Second, economic fragmentation is rising. This casts another shadow on the old growth model. There are no guarantees existing value chains remain relevant as in the past. Changing trade patterns and structural shifts such as AI and climate change, require re-allocating resources across sectors and larger investments, including in intangibles.

CESEE’s growth model needs to adapt to these challenges. What will it take?

A new growth model needs a financial system that supports innovation and adaption.

As a rule, innovators that bring productivity gains by means “of creative destruction” have little own resources, especially when it comes to R&D spending. They also have little collateral against which they can borrow.

And at a later stage of firms’ developments, financing is needed to bring inventions to scale.

A well-developed financial system caters to these different business risks and provides the menu of financing options over firms’ life cycle. It meets the needs of new firms, of established firms, as they upgrade or expand; and it allows for the growth of firms as they explore markets.

Such a financial system also ensures that savers find attractive options for their risk-return appetite and capital is channeled efficiently into productive capacity.

Measured by expected growth, capital should flow to CESEE firms since the implied return is well above that in advanced Europe.

Yet according to EIB (2018, 2023) surveys financing is insufficient.

- More firms in CESEE are financially constrained (9.1% vs. 6.1%) compared to the EU.

- Those that are leading innovator firms are usually even more constrained.

- And fewer firms in CESEE are content to rely on internal finance (17% vs 25%).

- As a result, 30% of firms perceive they have not invested enough.

And the scope of financing is not supportive of frontier technology adoption.

- The system is bank-based, which tends to favor conservative lending—not least because of the prudently regulated nature of the bank business.

- This bank-based system primarily supports investment in machinery and equipment, not intangibles, and…

- according to recent research by UNCTAD (2021, 2023), is the determining factor holding back CESEE country rankings in their preparedness for adopting frontier technologies.

These limitations are reflected in CESEE’s level of the capital stock, which has still a way to go.

Lifting the capital stock to the level where advanced European economies stood in 2000 –that goes hand-in hand with rising productivity—especially for intangible capital, could more than double income in CESEE.

So let us take a closer look at where CESEE’s financial system could improve.

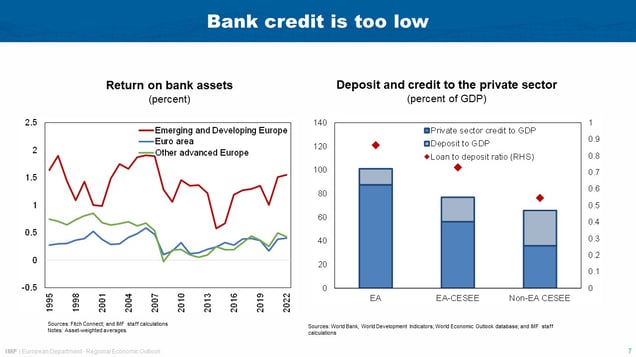

Much of the corporate sector draws on banks for external financing. Here, CESEE has two gaps that hold back financing.

First, intermediation needs to grow. For every euro deposited, non-CESEE EA banks provide credit to the private sector worth 86 cents. For CESEE this ratio currently stands at 1 euro to 73 cents in EA members and 55 cents for others.

Three factors contribute to the lower intermediation:

- Limited collateral,

- Lending conservatism amidst low recovery rates (EBA 2020), and post-GFC caution.

- Lack of competition. The latter is evidenced by structurally higher bank profits in CESEE than elsewhere in Europe.

Second, financial depth has clearly some way to go. Savings deposited with banks fall about 30 percent of GDP short of peers in the euro area.

Limited financial literacy and trust in the banking sector are potential culprits. According to the OeNB Euro Survey only 20 percent of individuals have a savings account in several non-EA CESEE countries. There appears to be a preference for cash holdings over interest bearing assets, often reflecting individuals’ lack of trust in the banking sector.

More deposits would expand available financing resources and bring down the cost of capital for firms; the primary reason for dissatisfaction with access to bank finance according to an EIB survey of firms (2023).

Banks can step up. But banks alone are not the answer. They are less suited to finance riskier ventures, inherent in the business models of innovative firms and start-ups.

Capital markets are the more natural fit. They cater to longer-term investors that accept higher risks for higher expected returns. In fact, the very absence of large capital markets and their promise of financing quells incentives of entrepreneurs to establish or grow their businesses.

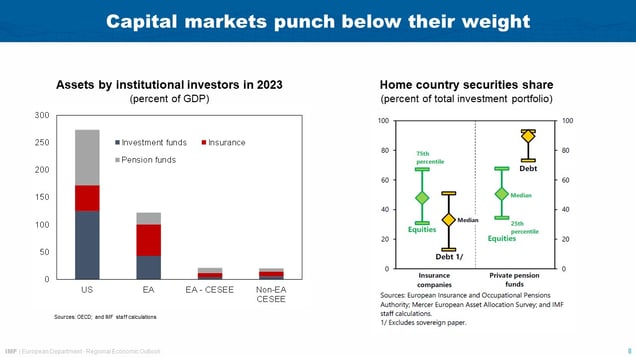

Currently capital markets in CESEE punch below their weight. Equity market capitalization in CESEE stands at about 20 percent of GDP. The corresponding value in the euro area is about 55 percent of GDP and in the US 160 percent of GDP. There is a huge shortfall but also a huge potential.

Growing the size of capital markets means finding demand for new market instruments that fund productive investments.

Institutional investors, such as insurances and pension funds, are the traditional counterpart, but their role in CESEE is limited. In the US, assets of these intermediaries exceed 250 percent of GDP. In CESEE, their assets stand at a staggering tenth of the US. Together with the large home bias of these investors—more than half of equity portfolio invested in their own countries’—and fragmented capital markets in Europe the scope for firm financing through capital markets is constrained.

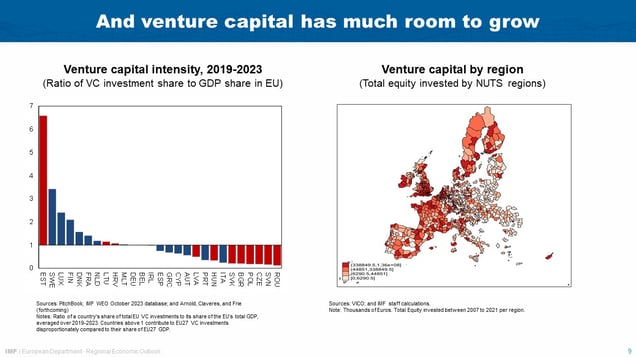

Finally, venture capital, a form of private equity, is arguably the highest risk-return funding source.

Venture capital is critical for a growth model based on advancing the technology frontier. Venture capitalists not only provide financing for innovation, which are hard to collateralize, but provide value-added by advising, monitoring, and supporting their chosen firms and projects.

In most of CESEE, venture capital lags more advanced country peers. On average venture capital as a percent of GDP accounts in CESEE for less than half the amount of financing in advanced European counterparts. The industry is characterized by fewer and smaller funds, reflecting the fragmentation of pools of capital in Europe.

Its scale is held back by underdeveloped capital markets. The smaller size of stock markets in Europe versus the US, limits “exit” options for successful startups, which ultimately impacts valuations and returns to investors. This reduces incentives to invest in startups throughout their lifecycle starting with venture capital.

The Baltics have shown that it is possible to scale up venture capital. And I look forward to hearing about their experience later today.

What can we take from this analysis?

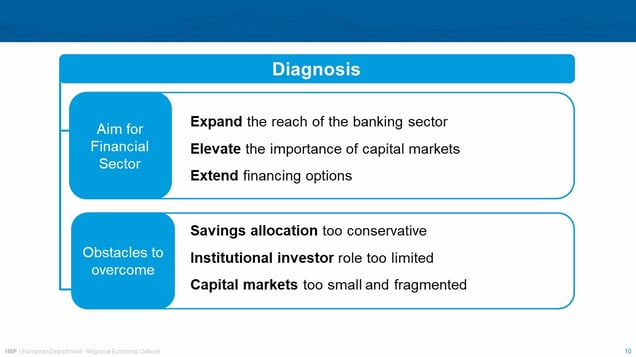

For the financial system in CESEE to support a new growth model adapted to the changing global context, hurdles need to be overcome.

First, households’ savings allocations are too conservative. More households hold cash, and for each euro households hold in bank deposits, about one euro is held in equity or investment funds. In the US, the corresponding value in equity and investment funds is almost four times this value. This makes for higher returns.

Second, institutional investors need to grow in importance as a vehicle to raise domestic savings and as source for risk capital.

Third, individual smaller and fragmented capital markets in Europe with large home bias of investors imply higher funding costs in CESEE.

Overcoming these hurdles would pave the way to

(1) expand the reach of the banking sector,

(2) elevate the importance of capital markets, and

(3) extend financing options.

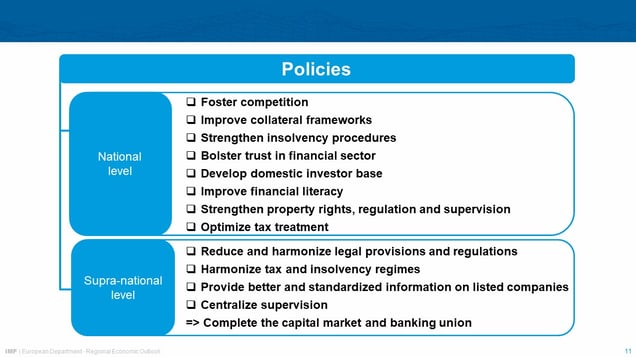

Policymakers can facilitate these changes.

At the national level, the expansion of bank lending can be accelerated by:

- Fostering competition through adequate regulation and supervision to reduce financing costs for firms.

- Improving collateral frameworks, and insolvency procedures to reduce risks associated with bank lending.

- Bolstering trust in financial institutions through transparent provision of information to expand the deposit base.

Measures to elevate the importance of the capital market are:

- Improving financial literacy which can help shift preferences away from cash to return-carrying asset holdings.

- Strengthening regulation and supervision, better protecting property rights, and developing the institutional investor base, including through Pillar II pension systems, which helps foster demand for market instruments.

And large capital markets also help grow venture capital by improving exit options for start-up firms. Where venture capital lags, well-designed preferential tax treatments can help overcome information asymmetries, and reap positive externalities not internalized by individual investors.

Supra-national initiatives can multiply these effects.

Capital market union and banking union need to be completed. This means harmonization of insolvency and tax regimes; better and standardized public information on listed companies, that is easily available, centralized supervision and common deposit insurance. This would reduce institutional investors’ home bias, encourage cross-border activity, allow for deeper pools of capital, and improve allocative efficiency.

Put simply: the border should not matter.

Deeper pools of capital in the EU mean fast growing firms seeking capital need not look to the US.

Yes, this may come with some risks, but we have learned from the GFC, to look out for these risks and prepare.

After all, for an entrepreneur who wants to flourish the biggest risk of all is not taking one.

Thank you.

References

EBA (2020) “Report on the benchmarking of national loan enforcement frameworks”, EBA/Rep/2020/29.

EIB (2023) “Investment constraints facing firms in Central, Eastern and South-Eastern Europe” Oct. 2023.

UNCTAD (2021,2023) “Technology and innovation report”.

IMF Communications Department

MEDIA RELATIONS

PRESS OFFICER:

Phone: +1 202 623-7100Email: MEDIA@IMF.org