(photo: FG Trade/iStock by Getty Images)

Fostering Inclusion in Mexico

January 24, 2022

Mexico has long suffered from high poverty and social exclusion. Although the COVID-19 pandemic has likely exacerbated these problems, an increase in social program spending helped lessen the negative impact on employment, retail sales, and poverty. Our recent staff paper argues that higher and more efficient spending on social programs, education, and health would reduce socioeconomic gaps, mitigate economic scarring from the pandemic, and foster an inclusive recovery.

Longstanding social vulnerabilities

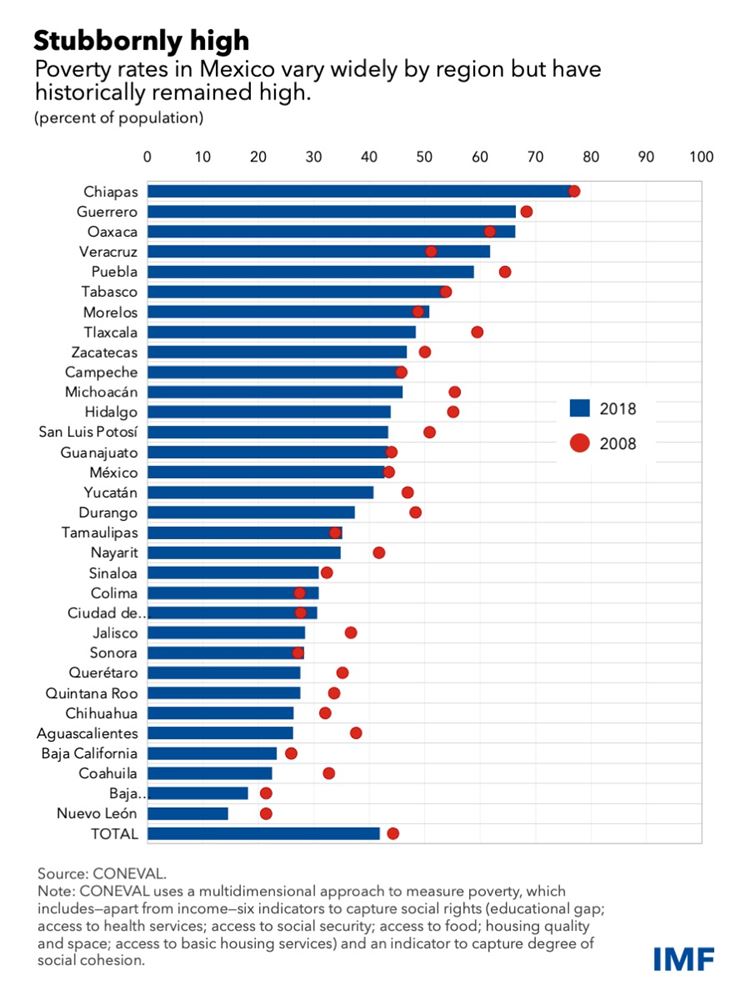

According to the National Council for the Evaluation of Social Development Policy (CONEVAL), about 42 percent of the Mexican population lived in poverty in 2018, with large variation across states.

The pandemic could worsen social vulnerabilities owing partly to Mexico’s limited social protection. Forty percent of households with children or adolescents did not have access to social protection prior to the pandemic, a share above the Latin American average. Another factor has been low spending on public health and education, which is below the OECD average.

Steps toward more inclusive social programs

Recognizing the poverty challenge, the government introduced important changes to social programs (social assistance and active labor market programs) in 2019, focusing on universal coverage and social (non-contributory) pensions, as well as support to indigenous people, the elderly, and people with special needs. These changes resulted in an increase of overall social assistance spending, from 1.8 percent of GDP in 2018 to 2.1 percent of GDP in 2019. Notably:

- Social pensions related to the Pensión para el Bienestar de las Personas Adultas Mayores program increased more than three-fold between 2018 and 2020, motivated by the prevalence of old-age poverty and limited pension coverage.

- In education, there are now three programs according to different education levels. One of them, Programa de Becas de Educación Básica para el Bienestar Benito Juárez, is for families living in poverty and with children under 15 years of age. Unlike Prospera, the discontinued conditional cash transfer program that paid per student, the payment is now per family and is not conditional on regular student health checks. The impact of this change should be monitored to ensure that school dropout rates do not increase and that student health and nutrition are not negatively affected.

The pandemic’s impact

The government had already budgeted for increases in social program spending in 2020 before the pandemic. Moreover, the government responded to the pandemic by increasing health spending and direct budget support to households and firms by 0.7 percent of GDP—a modest amount compared to other emerging market economies.

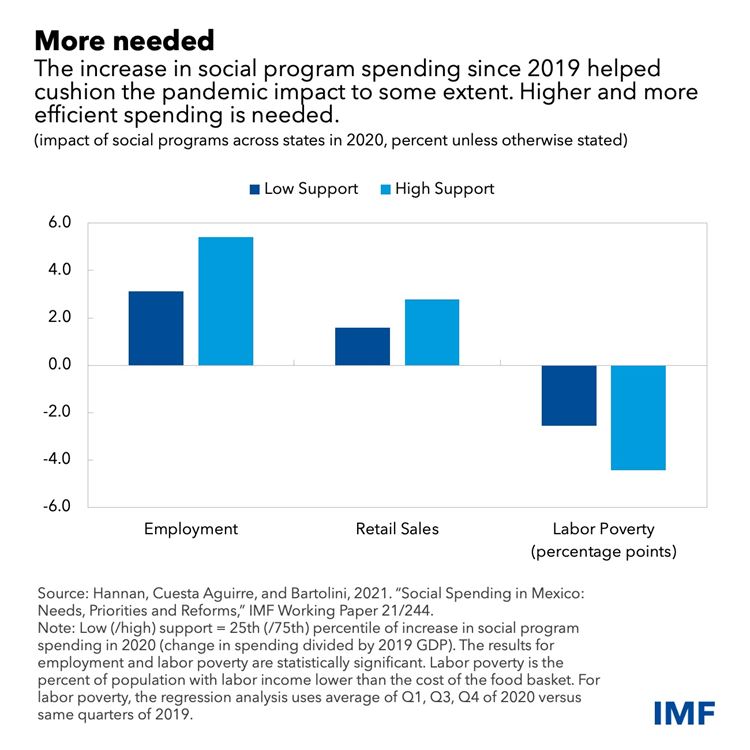

Our state-level analysis suggests that the social program spending increases in 2020 mitigated, to some extent, the pandemic’s negative impact on employment, retail sales, and labor poverty (the percent of population with labor income lower than the cost of the food basket).

Nevertheless, social vulnerabilities increased with the pandemic. The poverty rate increased from 41.9 percent to 43.9 percent between 2018 and 2020, while those lacking access to health services shot up by 12 percentage points of the population. CONEVAL finds that absent social transfers, poverty indicators would have worsened even further to 45.9 percent. In other words, social transfers prevented a further 2.5 million people from falling into poverty. Poor families are likely to be more affected by prospective economic scarring from the pandemic (for example, learning losses due to large gaps in internet access across income groups).

The need for more social spending

Higher and more efficient social spending remains essential to narrow socioeconomic gaps and secure an inclusive recovery, especially if coupled with reforms that improve employment and reduce informality.

Closing coverage gaps and limiting fragmentation in social assistance programs remains a priority. A single registry of beneficiaries and strengthened administrative capacity could reduce overlaps and improve the targeting of spending.

Given the large variation across states in education and health, priority should be given to more access to programs in poorer states and among the more disadvantaged populations. In education, investment in equipment, facilities, information technology, and modern infrastructure would help keep up with evolving labor demands.

To alleviate fiscal concerns, the higher social spending could be supported by higher tax collections over the medium term to ensure public debt declines over time. In the medium term, we estimate that tax reforms could finance spending of around 2 percent of GDP on social programs, education, and health, and 1 percent of GDP on infrastructure and other public investment.

***

Swarnali Ahmed Hannan is a Senior Economist in the IMF Western Hemisphere Department.