<Working in Germany during the pandemic. Kurzarbeit is a social insurance program whereby employers reduce their employees’ working hours instead of laying them off (photo: xxxxbr>

Working in Germany during a pandemic. Kurzarbeit is a social insurance program whereby employers reduce their employees’ working hours instead of laying them off. (photo: Patrick Pleul/dpa/picture-alliance/Newscom)

Kurzarbeit: Germany’s Short-Time Work Benefit

June 15, 2020

The COVID-19 pandemic has generated renewed interest in short-time work programs—the state-sponsored work-sharing schemes aimed at saving jobs. Kurzarbeit, Germany’s short-time work program, is widely considered the gold standard of such programs.

Related Links

What are the main features of Kurzarbeit?

Kurzarbeit is a social insurance program whereby employers reduce their employees’ working hours instead of laying them off. Under Kurzarbeit, the government normally provides an income “replacement rate” of 60 percent (more for workers with children).

That is, a worker receives 60 percent of his or her pay for the hours not worked, while receiving full pay for the hours worked. So, for example, a worker would only experience a 10 percent salary loss for a 30 percent reduction in hours. The program usually runs for a maximum of 6 months consecutively.

Kurzarbeit is, in many ways, an excellent crisis management tool. In a deep recession, it protects workers’ income and therefore supports aggregate demand. Since workers do not lose their jobs, they have less incentive to save on a precautionary basis. And companies retain firm-specific human capital, while avoiding the costly process of separation, re-hiring, and training.

It is also worth mentioning that Kurzarbeit is an addition to private working-hour flexibility arrangements. Employees in Germany are typically allowed to work overtime and accumulate credit on their “working time accounts”. These can then be drawn down during recessions with no effect on paychecks. Firms are allowed to use Kurzarbeit only when working time accounts are exhausted, which helps contain fiscal costs.

Are there any disadvantages to the program?

Some economists have argued that excessive reliance on Kurzarbeit during normal times could potentially reduce labor market flexibility, keeping workers in jobs that eventually need to disappear, and increasing the divide between workers in more and less protected segments of the labor market.

To avoid such outcomes, and limit the fiscal costs of the program, Kurzarbeit entails some co-financing components. In particular, the employer has to pay 80 percent of the total social security contributions owed on the reduced working hours. This cost-sharing element ensures that Kurzarbeit is not the first and only resort of employers who need to reduce production.

But all parameters of the program—including the employers’ share of social security contributions—can be relaxed during a serious crisis to discourage mass layoffs. This was the case during the global financial crisis and it is happening again now. These cyclical adjustments to the program help strike a delicate balance between providing relief during deep recessions, while not introducing too much rigidity into labor markets during normal times.

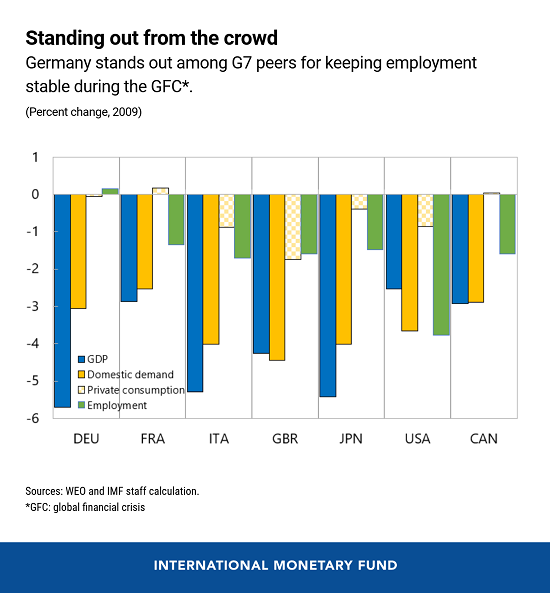

Germany was the only G7 country that did not experience a fall in employment in 2009. Remarkably, this was the case despite a large contraction in GDP (of almost six percentage points), owing mainly to a collapse of external demand.

Work-sharing was an important factor explaining this success. We estimate that about a third of the reduction in working time per employee was due to Kurzarbeit, with the rest explained by other margins of flexibility (such as running down working-time accounts and accumulated leave balances).

Other factors might have also been at play. It could be argued, for example, that the exceptional stability of employment in Germany during the global financial crisis was partly the result of earlier wage moderation, and a high degree of specialization of manufacturing workers, both of which made labor hoarding affordable for employers during the global financial crisis.

The strong performance of employment during the global financial crisis bolstered domestic demand, with stable labor income supporting private consumption, and reducing the need for precautionary savings. This opened the way to a rapid recovery.

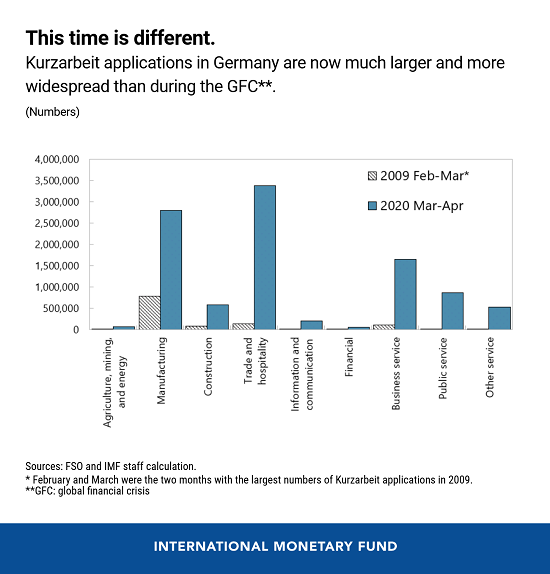

The pandemic is expected to have a much broader impact on the German economy than the global financial crisis. The global financial crisis mainly affected the manufacturing sector via collapsing import demand from trade partners. In contrast, the confinement measures taken to fight the pandemic have forced temporary business closures in many sectors. Therefore, several changes to Kurzarbeit’s features have been implemented or announced, with a view to making the scheme temporarily more attractive to employers and employees alike.

For workers, Kurzarbeit will now provide greater income protection if there is a prolonged reduction in work hours. The replacement rate, starting at 60 percent for the first three months, will increase to 70 percent during the 4th to 6th months, and further to 80 percent from the 7th month. The maximum duration of the program has been extended to 21 months. Moreover, the coverage will be expanded to temporary workers (about two percent of total employment).

For employers, the most important change is that their social security contributions have been waived. The requirement to exhaust working-time account balances before claiming Kurzarbeit has also been suspended.

Finally, firms no longer need to reduce working hours for at least 30 percent of their workers in order to be eligible for Kurzarbeit; the threshold has been lowered to 10 percent. Together, these changes make the scheme much more attractive to employers.

Kurzarbeit already seems to be playing an important role in preserving jobs during the current pandemic. From the beginning of March to the end of April, the number of workers who applied for Kurzarbeit exceeded 10 million, or about 20 percent of the labor force—a much greater number than peak applications during the global financial crisis—while unemployment has increased by less than 0.4 million.

What is your overall assessment?

Overall, the German government is doing precisely what should be done during deep recessions: making Kurzarbeit more flexible, more attractive to employers, and more generous to employees, while expanding coverage across sectors and across different types of jobs. This will come at an increased fiscal cost, but one that is well worth paying.

However, the profound impact of this crisis on the labor market cannot be overcome by Kurzarbeit alone. The pandemic is affecting far more sectors than the global financial crisis which, for Germany, was mainly a manufacturing story. In particular, marginal employees—who disproportionately work in the services sectors—do not make social security contributions, and are therefore not covered by Kurzarbeit.

They are among those likely to suffer the most from the sharp recession. To avoid potentially large social costs, the government should consider alternative ways to provide income support for this vulnerable segment of the population.