A resort in the southern Pacific. The economies of Pacific island countries depend heavily on tourism, which has collapsed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. (photo: Douglas Peebles/ Alamy)

Pacific Islands Threatened by COVID-19

May 27, 2020

Already among the most remote countries on earth, Pacific island states saw their vital economic links weakened in recent months with the evaporation of tourism, severe disruptions to international trade, and a reduction in remittances. For these countries, the COVID-19 pandemic may cut deeper than even some of the worst cyclones from years past.

Related Links

Shrinking global demand is also affecting the islands dependent on commodity and other exports—particularly those depending on oil and gas for revenue. And supply chain disruptions—including in the fisheries industry—continue to hinder the islands dependent on this sector, including for the licensing revenues.

Further, the ongoing effects of climate change and the tropical cyclone season (including Tropical Cyclone Harold, which hit Vanuatu, Tonga, Fiji, and the Solomon Islands in April) pose continued risks to these vulnerable economies. To sustain their economies during the crisis and contribute to a faster recovery, countries will need to allocate resources to vulnerable groups affected by the pandemic.

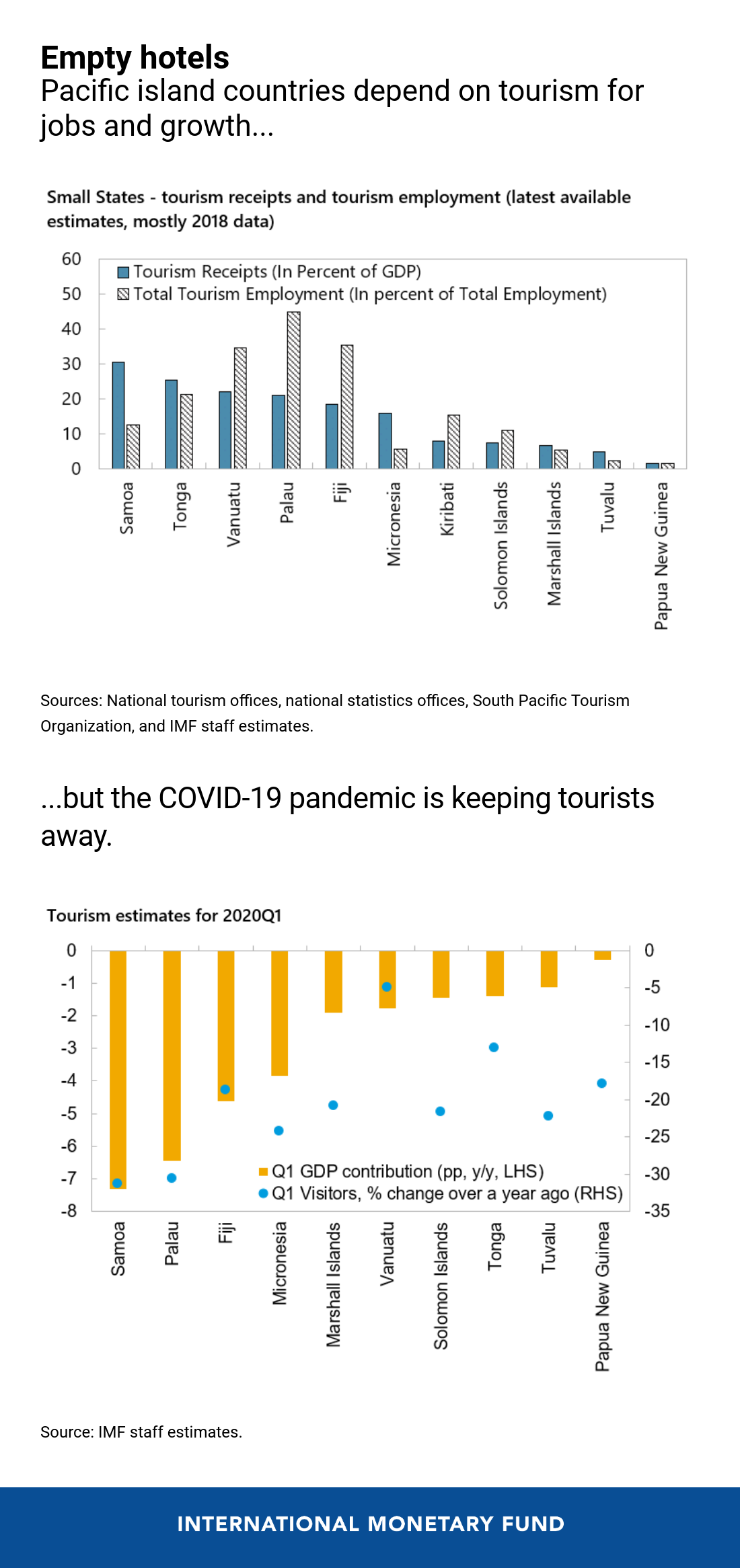

Collapse of tourism

Many island economies in the region are already reeling from the sharp collapse of tourism that followed on the heels of the pandemic. Tourism receipts are estimated to account for up to 20-30 percent of economic activity in countries like Samoa and Tonga and tourism is a prime source of employment and foreign exchange for such countries as Fiji, Palau, and Samoa.

Many of the islands were quick to react to the spread of the coronavirus, instituting travel restrictions and enhanced screening as early as January in an effort to keep the virus at bay—particularly for Samoa, which had just endured a devastating measles outbreak in late 2019. But with tourists from countries like Australia, New Zealand, and others in Asia unable or unwilling to travel due to the border controls and travel restrictions, hotels and resorts on the islands are effectively empty, forcing layoffs and closures.

Economic fallout beyond tourism

The drop in global demand is reflected in steep drops in commodity prices, affecting commodity exporters such as Papua New Guinea through a loss in exports and revenue. Moreover, energy companies could cut back production plans in anticipation of weaker energy demand resulting from a contraction in global manufacturing activity. For oil-importing countries in the region, lower oil prices will provide a buffer to the shock.

Globally, shrinking employment and repatriation of guest workers are expected to lead to a fall in remittances of around 20 percent. Remittances average about 10 percent of GDP in the Pacific islands (excluding Papua New Guinea) and exceed 40 percent in Tonga and about 15 percent in Samoa and the Marshall Islands.

Previous experience would suggest a rebound in commodity prices, tourism, and remittances after the COVID-19 crisis subsides. But the pandemic may inflict deeper wounds than even the worst natural disaster. Regional airlines—which are the essential conduit for tourism to these far-flung island economies—are facing significant damage from the prolonged loss of revenue. The potential for significant revenue losses and reduced operations, together with a chilling effect on global travel, could mean diminished tourism even after the virus recedes.

Policy response

Pacific island countries were quick to react to the threat of the pandemic—through measures to prevent the arrival of COVID-19 on their shores, containment (in Fiji) to limit spread, additional spending on health infrastructure and preparedness, and in seeking to counter the negative impact on economic growth and household incomes.

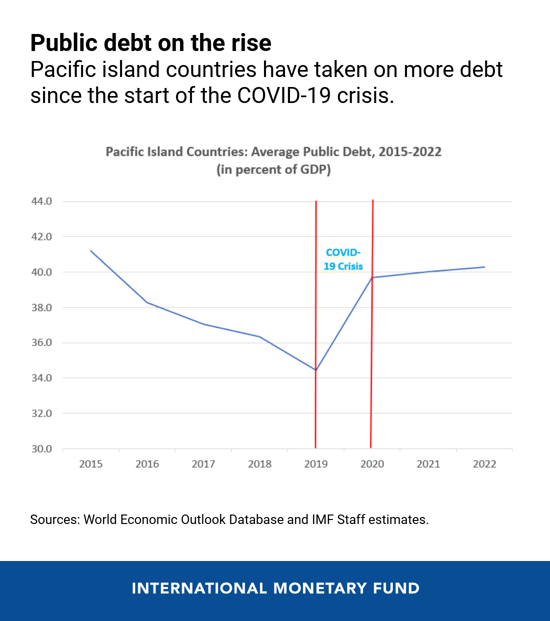

However, most countries in the region have limited room to counter the economic impact of the pandemic through additional spending. Public debt among the Pacific islands, on average, has already risen since the end of the global financial crisis. Now, some countries have announced fiscal packages that include, for instance, additional health spending, temporary cash transfers for displaced workers, and credit support to small and medium-sized firms and affected sectors.

Where feasible, central banks and regulators should play a complementary role to support economic activity. Central banks in Fiji, Papua New Guinea, and Vanuatu have reduced policy rates and/or reserve requirements. Other central banks in the region have also provided liquidity assistance in various forms. Some banks and other lenders have offered short-term payment deferrals and interest rate reductions on mortgages and loans, and waived late fees and charges to eligible customers.

To safeguard financial stability, supervisors should intensify monitoring and increase the reporting frequency of financial institutions. For Pacific island countries an important consideration will be to identify financial sector risks, including exposures to tourism-related activities, and conduct stress testing that ensures financial institutions are prepared to withstand shocks.

Stepping up IMF support

The IMF is working closely with the World Bank, Asian Development Bank, and other regional partners on innovative solutions and approaches to assist countries in the Pacific overcome the challenges of the current crisis and position themselves for economic recovery. The doubling of the IMF’s emergency financing capacity means that up to $643 million could be made available immediately to the Pacific island economies.

Solomon Islands has already received debt relief under the Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust. And a request for emergency financial support by Samoa under the IMF’s Rapid Credit Facility has now been approved. Emergency assistance for additional Pacific island countries will be considered by the IMF’s Executive Board in the coming weeks.