Opening Remarks at the Association of African Central Banks 2019 Symposium: Rising African Sovereign Debt: Implications for Monetary Policy and Financial Stability

July 31, 2019

Good morning.

Thank you very much for inviting me to give opening remarks at your annual symposium.

It is a real pleasure to be here with you all, particularly since you have selected a theme which touches on one of the pressing macroeconomic challenges facing policymakers in the region today.

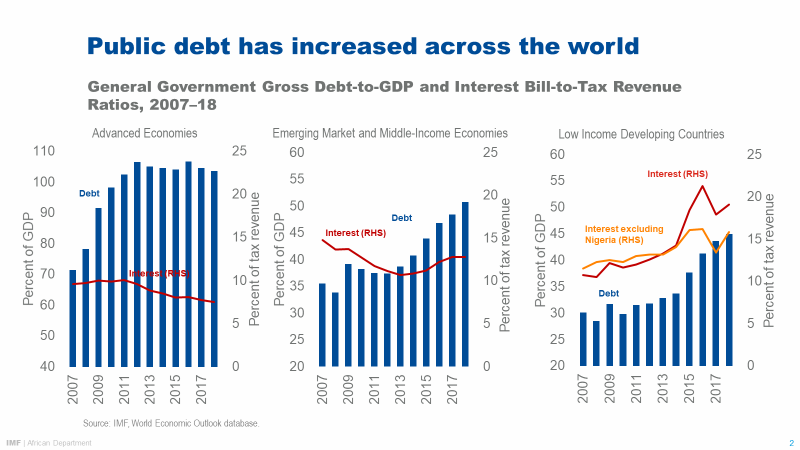

Public debt has increased in Africa, but also across the world. Public debt ratios are now significantly higher than before the global financial crisis in all country groups; and emerging market and developing economies face notably higher interest burdens.[1]

What are the implications of this rise? And, importantly, how does rising debt vulnerabilities affect the tasks of central banks? What does it mean for the conduct of monetary policy and the preservation of financial stability?

All of us here today are in some way grappling with these challenges. Today, I would like to share some thoughts with you on how to adapt to these new constraints.

I will begin with a brief summary of the main drivers of the increase in debt vulnerabilities in Africa and, then, spell out what this likely means for central banks.

Debt vulnerabilities in Africa

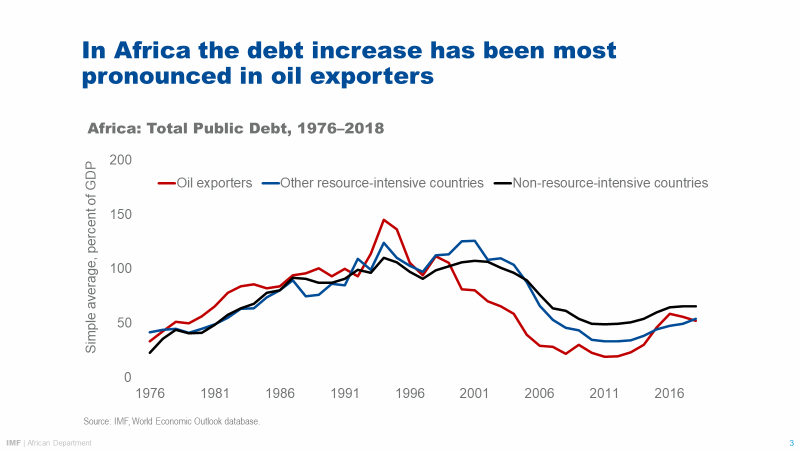

The stylized facts are well known to you by now. Countries in Africa have experienced a pronounced rise in sovereign debt, with average debt increasing by almost 20 percentage points of GDP between 2013 and 2018.

The region’s commodity exporters have been exposed the most, particularly oil exporters that were hit hard by the 2014-2016 slump in prices.

That said, other countries in the region have also experienced rising debt despite consistently high growth rates. The main drivers have been large primary deficits and valuation effects associated with exchange rate depreciation.

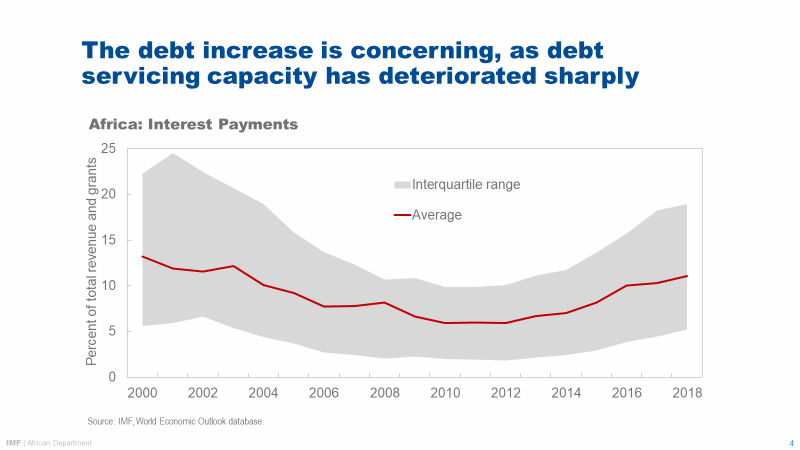

Part of the debt increase is central to a broader development strategy to use fiscal space for growth-enhancing investment—for example, infrastructure. Nonetheless, the increase is concerning as the capacity of countries to repay debt has deteriorated sharply. Interest payments on public debt as a share of government revenues are now close to their historic peak of the early 2000s. This reflects higher debt, greater reliance on non-concessional external financing against a backdrop of declining grants, and insufficient domestic revenue mobilization.

Our advice is always country specific but a key consideration for many countries now is to strike a better balance between much needed investment and debt sustainability.

The fiscal adjustment required to stabilize debt seems feasible. But for many countries stabilizing debt may not be a sufficiently ambitious target since almost half of low-income countries in sub-Saharan Africa are in, or at high risk of debt distress, according to the IMF/World Bank debt sustainability analysis. This means that operating in an environment of high public debt is not a short-term challenge, but one that governments will likely face for some time to come.

Given this, it is important to consider the implications for central banks.

In particular, I would like to set out five myths on the impact of public debt on central banking, which have been aired recently in various contexts.

Myth 1. Fiscal dominance is a preoccupation of the past.

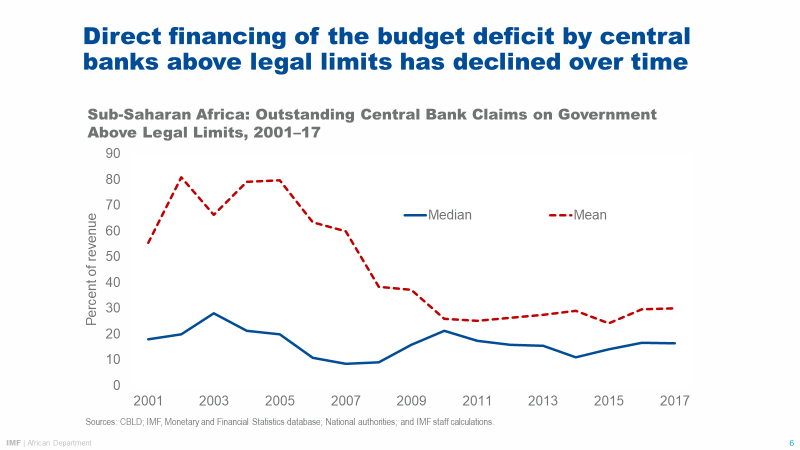

This view—that fiscal dominance is no longer a major problem in most countries—is not without foundation. When we look at the traditional definition of fiscal dominance, direct financing of the budget deficit by central banks above legal limits has declined over time, especially during the second half of the 2000s. Legal limits have also been tightened and so there is less room within the legislation to put pressure on central banks to lend to the government.

But let’s look beyond that. If we adopt a broader view of fiscal dominance, government influence on the work of central banks continues to prevail.

I should add here that outside the context of high public debt, pressure from the government and politicians on the activities of central banks is not just an Africa-specific phenomenon.

Let me give you three examples of how this “soft” form of fiscal dominance manifests itself today.

First, governments may be tempted to pressure central banks to maintain accommodative financial conditions in order to contain domestic borrowing costs.

Some anecdotal evidence suggests that finance ministers push for policy rate cuts when they face a tight fiscal situation.[2]

Second example: fear of floating is magnified when foreign currency debt is high.[3]

In this context, there may be a desire to limit exchange rate depreciation due to currency mismatches and the negative effect on public sector balance sheets and debt servicing costs. This tilts the balance for central banks away from using the exchange rate as a shock absorber and encourages greater intervention, possibly leading to volatility in domestic interest rates.

Third example of soft fiscal dominance. In situations where economic growth is weak and supportive fiscal policy is constrained by high public debt, the central bank is often called to take a more proactive approach to supporting the economy.

This may lead the central bank to provide subsidized lending to the private sector or to troubled state-owned-enterprises.

More worrisome still, high public debt can create pressures to expand the central bank mandate beyond price stability As we are currently hearing in South Africa.

Myth 2. As long as public debt is sustainable, its level is irrelevant for monetary policy and financial supervision.

Let me now turn to the second myth. There may be a sense among some that when public debt is sustainable, little attention is needed from central banks.

I would like to give some reasons as to why high public debt, even if it is sustainable, can complicate the work of central bankers significantly.

First, it is well known that high public debt weakens the transmission of monetary policy. High public debt crowds out private debt, resulting in shallow credit markets and fiscally-induced pressures on interest rates.[4] This reduces the impact of monetary operations on domestic financial conditions.

Another reason why high debt complicates monetary policy is because it generates more complicated tradeoffs. In cases where there is high foreign currency public debt and if there is a negative shock to economic activity, the sovereign risk premium may increase, leading to a nominal depreciation of the currency. Monetary policy then needs to raise interest rates to limit the depreciation, but this further weakens domestic growth and puts pressures on domestic government borrowing costs. This is a tough choice to make.[5]

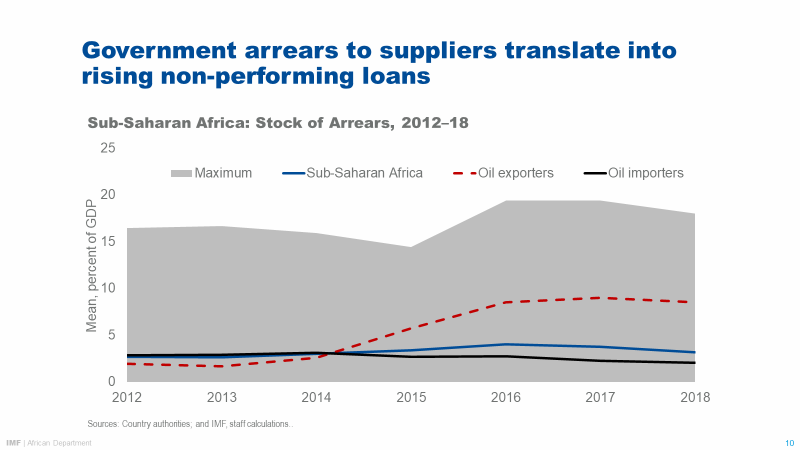

Finally, high public debt can create financial stability risks. A key channel in Africa is government arrears to suppliers. As we currently see in quite a few countries in the CEMAC, banks’ non-performing loans have risen significantly partly because government arrears to suppliers prevent the private sector from repaying its bank loans.

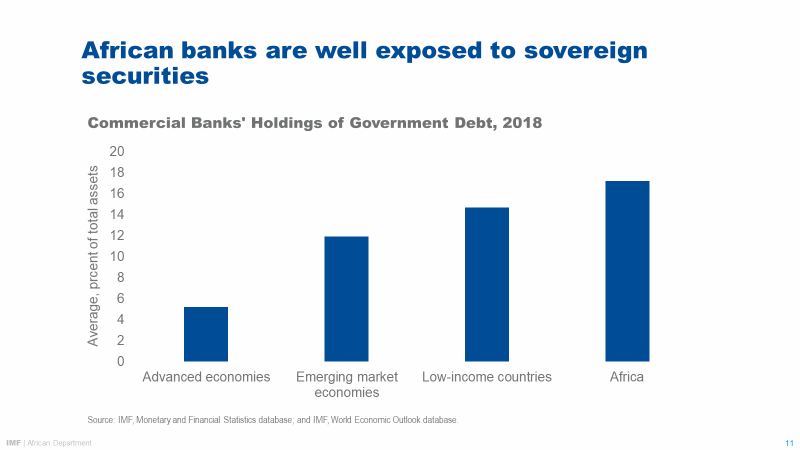

Another channel of transmission of debt to the financial sector is the exposure of commercial banks to government paper. This exposure feeds the bank-sovereign nexus and can endanger financial stability when the risk premium on government securities increases.

African banks have significant exposure to sovereign securities. These account for more than a quarter of the banking sector balance sheet in several countries.[6]

Myth 3. There is little that central banks can do to protect themselves and the financial sector.

The third myth that I would like to discuss is the notion that central banks have limited policy tools to manage the spillovers of high public debt to monetary policy and financial stability.

While the central responsibility for public debt management lies with Finance Ministry, central banks can still take some important actions. These include:

- Continue to strengthen the monetary policy framework. How? By reinforcing the operational and financial independence of central banks; and creating better accountability mechanisms, such as an explicit interest target and inflation objective.

- Step up communication on the role of the central banks. This means: tailoring it to different audiences, making it simple, and expanding its reach to a broader understanding of policy decisions and trade-offs.

- Address the bank-sovereign nexus. By reducing incentives for banks to hold government securities, for example through changes to tax deductibility and exemptions. And by applying macro-prudential policies. For instance, in the CEMAC, the risk weights applied to member states sovereign debt depend on their compliance with the regional convergence criteria.

- Finally, improve debt data collection to feed central bank forecasting, monitoring, and modeling efforts. In particular, broaden the coverage of debt statistics beyond the central government to give a more complete picture of fiscal vulnerabilities.

Of course, there is no silver bullet. All these actions cannot ensure that central banks will be fully protected against government influences. South Africa is a good example of a country where the central bank has come under scrutiny despite or perhaps because of its sound institutional framework. It seems to me that in a world where central banks have more independence, they can also become more exposed to criticism, and must redouble their efforts to ringfence their policymaking role to meet financial and monetary objectives.

Myth 4. There is a still clear delineation of roles between monetary and fiscal policy.

The fourth myth is about the division of responsibilities between monetary and fiscal policy.

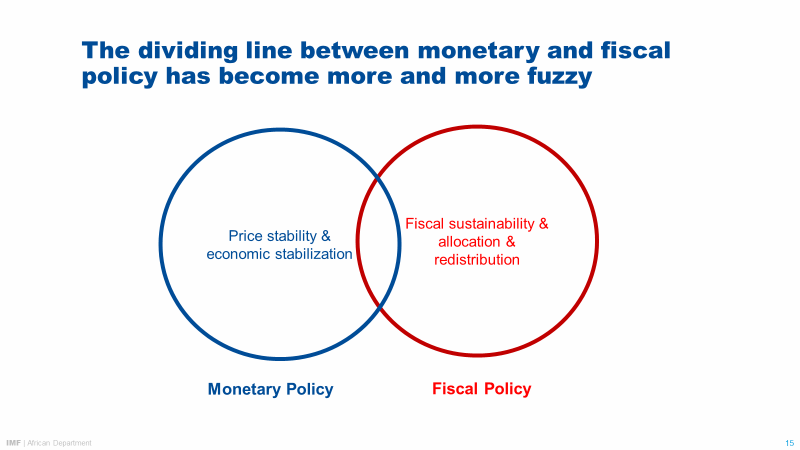

Before the global financial crisis, there was a consensus that monetary and fiscal policies had well defined and separate roles.

Monetary policy was, in general, responsible for smoothing out the economic cycle and ensuring price stability, while fiscal policy had to ensure public finances remained sustainable. And the objective for many emerging and low-income countries was to move toward this delineation of responsibilities—for instance with the introduction of fiscal rules and inflation targeting frameworks in the 2000s.

However, with the global financial crisis, the dividing line between the two policies has become more and more fuzzy.

In the past decade, fiscal policy has gained more legitimacy and responsibility for stabilizing the economic cycle—a role traditionally assigned to monetary policy, which had lost some effectiveness. At the same time, monetary policy has increasingly resorted to “unconventional” measures that have some characteristics of fiscal policy—for instance the purchase of private sector assets.

I think this overlap of roles and lack of clarity creates challenges, especially in developing countries. It can foster negative spillovers across policies. I have already discussed many of the negative effects that a loose fiscal policy can have on the conduct of monetary policy.

Therefore, to the extent possible, the ministry of finance and the central bank should strive to better define their respective roles and joint responsibilities in macroeconomic management. Any commingling of jobs—for instance with central banks carrying out quasi fiscal operations—should be avoided, except in exceptional circumstances when monetary policy is severely constrained, and the financial sector is impaired.

Myth 5. Central banks can help governments alleviate the public debt burden.

Let me finish with a last myth. One dimension of possible overlap between monetary and fiscal policies is the preservation of debt sustainability. Some argue that central banks can help governments alleviate the public debt burden. I don’t believe that this is the case. The scope for central banks to lower the debt burden seems very limited, at least in Africa.

I will briefly discuss three main ways monetary policy could help to reduce debt: (i) by generating a surprise in inflation; (ii) by transferring seigniorage revenues to the budget; and (iii) by introducing financial repression regulations.

- First, should and can central banks create an inflation surprise to lower debt?

Research shows that inflation surprises can only reduce debt partially and temporarily until debt is rolled over at higher interest rates.[7]

And it is even less likely to work in Africa, where public debt has a relatively short maturity, inflation is mostly driven by supply shocks, and there is a substantial share of debt in foreign currency.

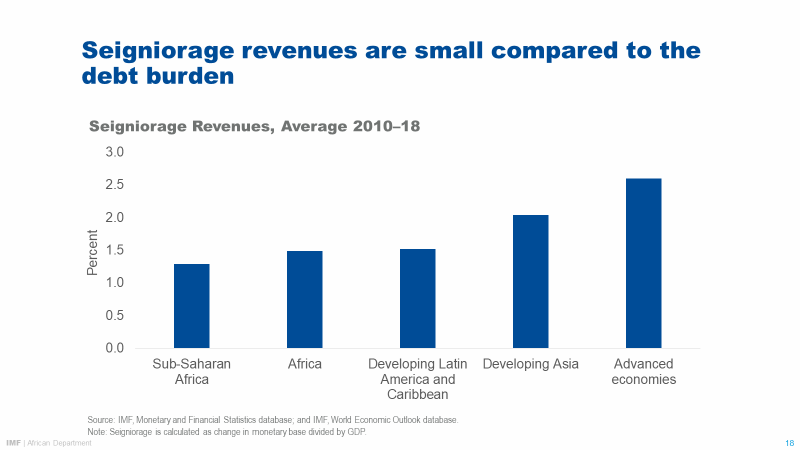

- Second, could the central bank help improve the government fiscal balance by transferring higher seigniorage revenues?

Estimates suggest that seigniorage revenues, proxied by the change in the monetary base, are about 1 to ½ percent of GDP per year on average in Africa, and only part of these revenues are transferred to the budget according to national rules.

While this is not negligible, it is unlikely that central bank profits could contribute meaningfully to the debt reduction in Africa, where the debt ratio of a majority of countries exceeds 50 percent of GDP.

- Finally, could financial repression be relied on to help?

Debt dynamics in Africa benefit from a persistently negative interest-growth differential. Despite high economic growth, interest rates on government debt remain relatively low. This is partly because of the high share of concessional debt, but in some countries financial repression also plays a role—for instance by creating a captive audience for government securities.

This raises the question of whether central banks could do more of this. Again, this brings us back to my initial point about constraints and trade-offs for policy making.

One constraint is that financial repression is more effective when the capital account is closed, which is not the case anymore in many countries in the region.

Moreover, financial repression creates distortions in the financial sector that need to be carefully considered against the distortions brought by higher taxes if fiscal consolidation was used to reduce debt. It is also a matter of societal preference, since financial repression shifts the cost of debt reduction from taxpayers to bondholders.

Let me end by noting once again that central banks are under pressure around the world—so you are not alone in grappling with these challenges. But there are ways of responding to these new challenges. And I think that rising public debt is another strong rationale for moving towards a more transparent, resilient, and forward-looking monetary policy framework.

Thanks again for the invitation to be here. There is much for us to discuss and I look forward to the sessions ahead of us.

Murakoze Cyane!

[1] In 2019, public debt in advanced economies is over 100 percent of GDP, 50 percent of GDP in emerging economies and developing economies, 57 percent of GDP in Africa, and 50 percent in sub-Saharan Africa (GDP-weighted averages).

[2] For instance, the inflation performance in Ghana after adopting inflation targeting in 2007 was to a large extent influenced by traditionally strong fiscal pressures which took the form of direct monetization of deficits and pressures on the Bank of Ghana to maintain more accommodative monetary policy stance than was desirable. (See “Evolving Monetary Policy Frameworks in Low-Income and Other Developing Countries—Background Paper—Country Experiences”, IMF Board Paper, 2015).

[3] In a sample of 15 emerging market economies, countries with large foreign exchange debt (both private and public) tend to react more strongly to exchange rate changes using both FX interventions and monetary policy. See “Floating with a Load of FX Debt?”, Kliatskova and Mikkelsen, IMF WP/15/284.

[4] Budget deficits have a greater impact on domestic interest rates when, domestic debt is high, domestic financial development is limited, and capital accounts are restricted—three conditions more likely to be met in low-income countries. See “Budget Deficits and Interest Rates: A Fresh Perspective”, Aisen and Hauner, 2008, IMF WP/08/42.

[5] History provides multiple examples of procyclical monetary response when public debt is high, and the currency depreciates. See the experience of several emerging markets in the early 2000s: Columbia, Indonesia, Turkey, Venezuela. Described in Mohanty and Scatigna, 2003, “Countercyclical fiscal policy and central banks,” chapter in “Fiscal issues and central banking in emerging economies,” vol. 20, pp 38-70 from Bank for International Settlements.

[6] Countries with a share of government debt in total assets above 25 percent in 2018 include Ghana (29 percent), Sierra Leone (34 percent), South Sudan (48 percent), Angola (34 percent), Mozambique (28 percent), Burundi (37 percent). Based on countries reporting to IFS.

[7] See Reis, 2016, “Can the Central Bank Alleviate Fiscal Burdens?” NBER Working Paper No. 23014.

IMF Communications Department

MEDIA RELATIONS

PRESS OFFICER: Meera Louis

Phone: +1 202 623-7100Email: MEDIA@IMF.org