Kuala Lumpur’s illuminated skyline: Malaysia’s strong economy is on its way to achieving high-income status (photo: Matthew Williams-Ellis/robertharding/Newscom)

Malaysia's Economy: Getting Closer to High-Income Status

March 7, 2018

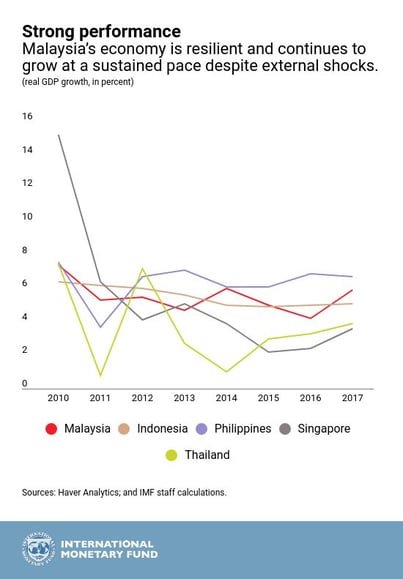

Malaysia’s economy continues to perform strongly, with higher than anticipated growth at 5.8 percent in 2017, and projected growth of 5.3 percent for 2018, according to the IMF. The country is well on its way to achieving high-income status. But to pass the finish line, the authorities will have to step up reforms to boost productivity and raise living standards for its 32 million citizens.

IMF Country Focus sat down with Nada Choueiri, IMF mission chief for Malaysia, to discuss a few of these key recommendations, as well as the report’s overall findings.

The IMF just completed its annual assessment of the Malaysian economy. How is the economy doing?

Malaysia’s economy is showing resilience and is performing strongly. Growth is running above potential, driven by strong global demand for electronics and improved terms of trade for commodities, such as oil and gas. On the domestic front, Malaysia’s strong employment is boosting private consumption, and investment is also helping to drive growth.

Malaysia’s economy is on its way to achieve high-income status. What are some of the priorities outlined in the government’s 11th Malaysia Plan that will help the country get there?

The 11th Malaysia Plan, covering the years from 2016 to 2020, charts a path toward advanced economy status and greater inclusion. Increasing productivity and encouraging more innovation are core objectives of the plan, which has six strategic pillars that touch on a range of development issues―including equity, inclusiveness, environmental sustainability, human capital development, and infrastructure.

The plan also puts significant emphasis on improving labor market outcomes and targets increases in labor’s share of income, female labor force participation, and skilled labor employment, as well as improvements in education quality and matching skills to industry needs.

As Malaysia’s public debt continues to decline, the IMF is recommending that the government shift toward raising revenues, rather than achieving its goals through continued cuts in public spending. How would this impact the trajectory of debt and social spending priorities?

Over the past three years, the federal government deficit was reduced from 3.4 percent of GDP in 2014 to 3 percent of GDP in 2017. This is helping bring down debt. Deficit reduction was achieved mainly through expenditure cuts, although the introduction of a Goods and Services Tax in 2015 also helped. Looking ahead, our advice to the authorities is to maintain gradual fiscal consolidation but, at the same time, also continue to increase revenue to protect social and development spending.

Malaysia’s household debt to GDP ratio—at 84.6 percent for 2017—is high compared to similar countries. Why is this an important number to keep track of, and what does it mean for economic growth prospects?

Households borrow to be able to spend more when their income is not high enough, and in anticipation of higher income later. This is positive for households’ standards of living and for economic growth.

Still, when household debt increases too rapidly compared to economic growth or reaches very high levels, it represents a vulnerability, and it could have a negative impact on both households and the banking sector in the event of an unexpected economic shock. But risks associated with high private debt are reduced if households also possess sizable assets, which is the case in Malaysia. So, household debt per se is not a negative feature, but it needs to be watched carefully.

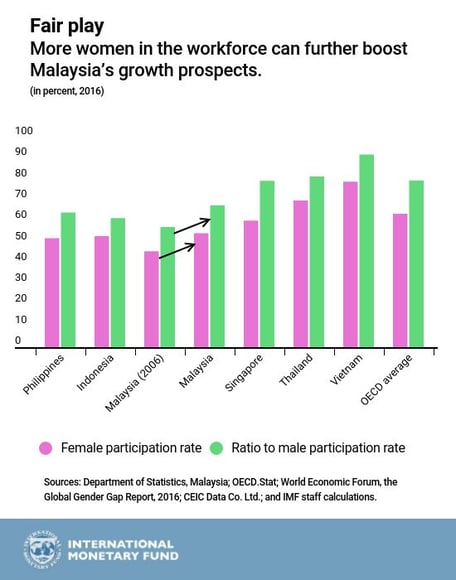

You mentioned that improving labor market policies, such as encouraging more women to enter the formal workforce, can help secure Malaysia’s long-term growth prospects. How does this benefit the economy?

The economy always benefits when production increases. Economic activity picks up when you put more inputs to work, particularly more labor. And an important and direct way to raise labor input is by encouraging more women to work. We saw that in Malaysia in recent years: between 2010 and 2016, female employment grew at an annual rate of about 4½ percent, more than tripling women’s contribution to real GDP growth, relative to 2001-08.

Looking at it from another angle, if the female labor force participation rate had not changed since 2012, real GDP would have been about 1 percent lower in 2016 compared with what it actually was that year. But despite this progress, female labor force participation remains low, at just above 54 percent, both in absolute and relative terms (the male participation rate is about 80 percent). So more needs to be done to make sure it keeps increasing and contributes positively to the economy.