Typical street scene in Santa Ana, El Salvador. (Photo: iStock)

IMF Survey : Low-Income Countries Show Comeback in Growth Performance

April 9, 2013

- Growth in low-income countries has strengthened in past 20 years

- Recent growth spurts based on better economic policies

- Continued policy reforms key to sustaining strong low-income country performance

Low-income countries have bounced back in the past two decades. Analysis in the International Monetary Fund’s latest World Economic Outlook (WEO) suggests that dynamic low-income countries are on a stronger economic footing today than before the 1990s, and therefore better placed to stay on course.

Oil derricks in Baku, Azerbaijan. Resource-rich low-income countries have seen the strongest growth (photo: David Mdzinarishvili/Reuters/Newscom)

WORLD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK

After a first wave of growth takeoffs—expansion in per capita output for at least 5 years averaging at least 3 ½ percent a year—by low-income countries in the 1960s and early 1970s, there were fewer in the 1980s. Growth in many of these countries decelerated as global economic conditions deteriorated. A second wave of takeoffs started in the 1990s (see Chart 1).

A key concern today is whether recent takeoffs by low-income countries could unravel like some did in the past, especially if global growth remains sluggish. The IMF study suggests that such risks are lower today. The study analyzes growth takeoffs in more than 60 low-income countries over the past six decades.

More sustained takeoffs

The authors find that recent takeoffs by low-income countries have lasted longer than those before the 1990s: more than half of today’s dynamic low-income countries continued their expansion through the Great Recession.

Growth takeoffs are not confined to commodity producers; they were accomplished by low-income countries that were rich in resources, manufacturing oriented, and others. “There also seems to be more at play than strong global conditions in helping takeoffs, as many low-income countries, whether resource- or manufacturing-oriented, were unable to take off despite supportive global conditions,” said John Bluedorn, one of the study’s authors.

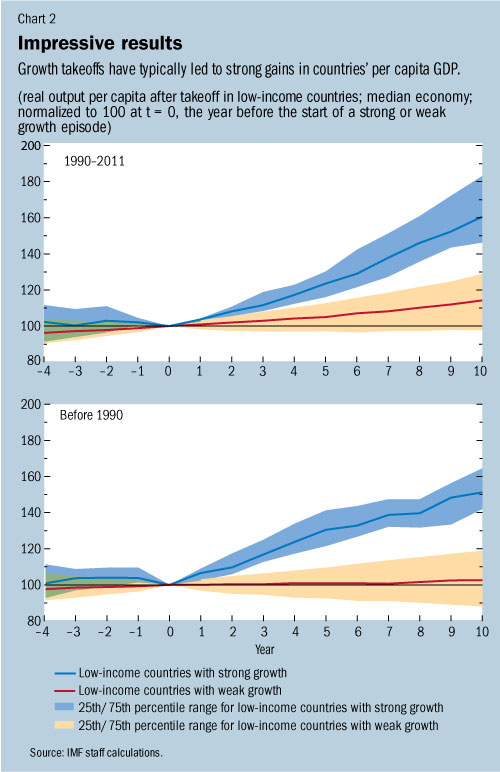

Takeoffs in both generations typically paid off, with a 50–60 percent rise in per capita income over the 10 years after takeoff, in contrast to much smaller gains for low-income countries that did not take off (see Chart 2). “This is an important message for some two-thirds of today’s low-income countries that have yet to experience a growth take off,” highlighted Jaime Guajardo, another author of the report. “That said, concerns rise from the fact that some takeoffs in the previous generation eventually experienced reversals in income gains. The question in many policymakers’ minds is whether this time is different.”

Policy foundations firmer in recent takeoffs

The research finds important similarities between takeoffs in both generations. Both saw higher investment rates and export growth than low-income countries that did could not take off. This underscores the well-established roles of capital accumulation and trade integration in development.

There are also striking differences across the two generations, providing assurance that today’s takeoffs are more resilient than those in the past. Countries in recent takeoffs saw declines in inflation and in public and external debt levels, whereas past takeoffs resulted in wider imbalances (see Chart 3). “This is partly related to countries’ greater reliance on foreign direct investment, and partly because strong growth was upheld despite lower investment than in the previous generation,” said Nkunde Mwase, another coauthor of the study.

Recent takeoffs have also seen a stronger record on structural reforms and institutions, such as a lower regulatory burden, better infrastructure, higher education levels, lower income inequality, and greater political stability.

Reform momentum should continue

Drawing on historical experiences, the study documents that although low-income countries were able to take off by reducing imbalances, not all maintained their progress. Those that persisted in addressing vulnerabilities or implementing reforms that helped raise productivity enjoyed sustained growth (Indonesia and Korea in the 1960s to the 1980s). Where imbalances widened, takeoffs ended disruptively or were interrupted even after decades of strong growth (for example, Brazil in the 1980s and Indonesia in the 1990s).

“The key takeaway for today is that LICs must avoid overstimulating demand or accumulating excessive external debt despite ultra-low global interest rates,” said Rupa Duttagupta, who led the research work.

The study concludes that if today’s dynamic low-income countries preserve momentum in their policy reforms, they are likely to avoid the setbacks that afflicted many of their predecessors. “Sustained effort is needed to reduce imbalances, and confront many challenges, such as growth that is concentrated in a few sectors, or that has not yet translated into broad-based rise in living standards and declines in poverty levels.” Duttagupta stressed.