عربي, 中文, Español, Français, 日本語, Português, Русский

New IMF research finds that macroeconomic factors, not tariffs, explain most of the changes in trade balances between two countries.

Bilateral trade balances (the difference in the value of exports and imports between two countries) have come under scrutiny recently. Some policymakers are concerned that their large and rising size are the result of uneven measures that distort international trade. But is a focus on bilateral trade balances the right one?

The short answer is no. Our research in Chapter 4 of the April 2019 World Economic Outlook finds that a tariff-induced change in a specific trade balance between two countries tends to be offset by changes in bilateral balances with other partners through trade diversion, with little or no impact on the aggregate trade balance (the sum of all the bilateral trade balances).

Most of the changes in bilateral trade balances over the past two decades were explained by the combined effect of macroeconomic factors.

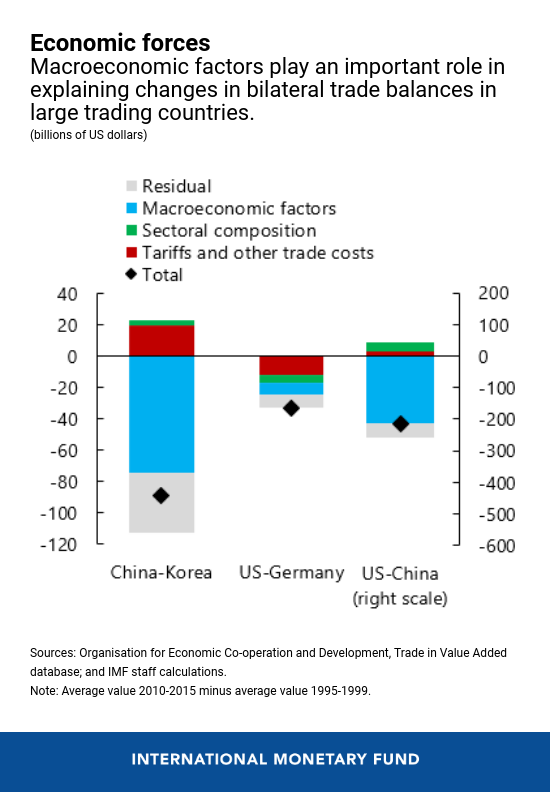

Instead what drives trade is macroeconomics. We find that most of the changes in bilateral trade balances over the past two decades were explained by the combined effect of macroeconomic factors—which include fiscal policy, credit cycles, and, in some cases, exchange rate policies and widespread subsidies to tradable sectors. In contrast, changes in tariffs played a much smaller role.

This does not mean that tariffs do not hurt countries. In the context of a global economy characterized by global value chains (where production is carried out across multiple countries), sharp increases in tariffs can create significant long-term economic costs and ripple effects, leaving the global economy worse off.

Economic forces explain bilateral trade balances

Our work—based on a study of 63 countries over 20 years and across 34 sectors—sets out to understand and quantify the drivers of changes in bilateral trade balances. It does so by distinguishing between the roles of macroeconomic factors, tariffs, and the international organization of production—in part reflected in the sectoral composition of countries’ production and demand (for example, manufacturing, services, or agriculture).

We find that the evolution of bilateral balances over the past two decades has been, to a significant extent, driven by macroeconomic forces that are also known to determine aggregate trade balances. These factors include fiscal policy, demographics, and weak domestic demand, but they may also include exchange rate policies and domestic supply-side policies, like subsidies to state-owned enterprises or to export sectors.

In contrast, changes in bilateral tariffs played a smaller role, reflecting their already low levels in many countries and the fact that reciprocal tariff reductions had offsetting effects on bilateral trade balances. The chart shows the contribution of each of these factors in the evolution of bilateral trade balances for some large country-pairs. For example, macroeconomic factors accounted for about 20 percent of the change in the US-Germany trade balance over 1995-2015 but over 95 percent of the change in the US-China trade balance.

A closer look at tariffs and their spillovers

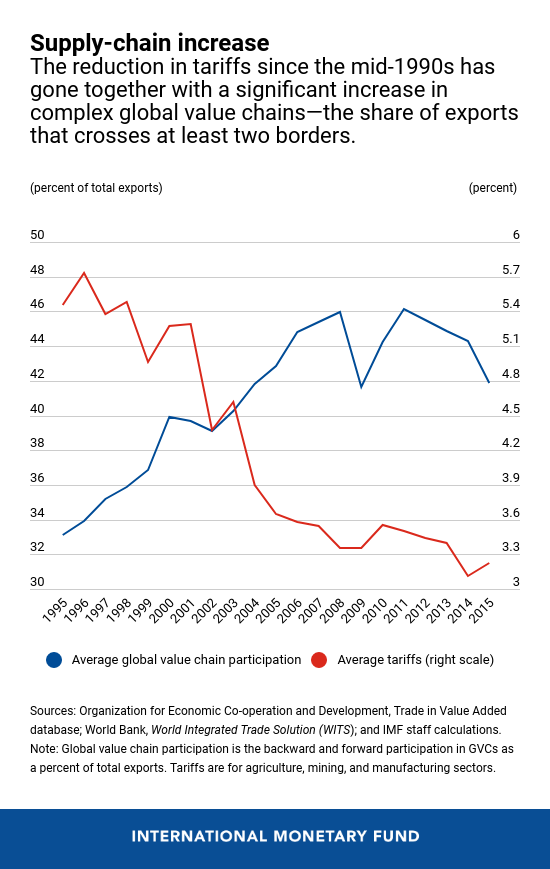

While our analysis finds that the direct impact of tariffs on the evolution of bilateral trade balances has been small relative to macroeconomic factors, this doesn’t mean that tariffs don’t matter. In the longer term, large and sustained changes in tariffs can shape the international organization of production as firms adjust domestic and international investment and production structuring, such as organizing themselves into global value chains—the different processes in different parts of the world that each add value to the goods and service being produced.

Since the mid-1990s, the significant decline in trade costs—that is, tariffs and transportation and communications costs—has gone together with an increase in the extent and complexity of global value chains. This has allowed countries to become more productive and create jobs.

The integrated nature of the current global trade system suggests that a sharp increase in tariffs would impact countries and create a ripple effect from one another, leaving the world economy worse off. We find that increases in tariffs would particularly hurt output, jobs, and productivity, not only for those economies directly imposing and facing them, but also for other countries up and down the value chains.

For most countries, the negative effect of a generalized 1 percentage point increase in manufacturing tariffs (not accounting for any feedback effects) is larger today than it would have been in 1995. In the case of Germany and Korea—countries with large manufacturing sectors that are particularly highly integrated into global supply chains—the difference is about 0.5 and 0.6 percent of GDP, respectively.

When tariff increases are targeted to specific partners (instead of being deployed across the board), some countries may benefit from trade diversion as the demand from the country imposing the tariff is switched to countries that face no tariffs. Hence, changes in the bilateral trade balance with specific partners, triggered by bilateral tariffs, tend to be offset by changes in bilateral trade balances with other trade partners, leaving the aggregate trade balance broadly unchanged.

Policy implications

These findings support two main policy conclusions.

First, the discussion of trade balances should focus on macroeconomic factors, which tend to determine aggregate trade balances. Policymakers are well advised to avoid distortive macroeconomic policies such as procyclical fiscal policy (providing stimulus when demand is already strong) or heavily subsidizing exporting sectors that create excessive—and possibly unsustainable—imbalances. Unless there are changes in macroeconomic policies, targeting particular bilateral trade balances will likely only lead to trade diversion and offsetting changes in trade balances with other partners, leaving the country’s aggregate balance little changed.

Second, multilateral reductions of tariffs and other non-tariff barriers (for example, of import quotas or varying product standards across countries) will benefit trade and, over the longer term, improve economic outcomes. Policymakers should continue to promote free and fair trade by undoing recently enacted tariffs and enhancing efforts to reduce existing barriers to trade.

At the same time, it is critical to recognize that trade liberalization—like technological progress—can impose costly adjustment for some groups of workers and communities. Putting in place policies such as retraining and job search assistance programs, adequate social safety nets and redistributive tax-benefit systems can help ensure that the gains from trade are more widely shared and individuals or groups left behind are adequately protected.

Watch a conversation with the author:

Related Links:

How to Keep Corporate Power in Check

Why Investment May Come Under Threat