Latin America, while still comparatively young, is aging fast. Our research finds that population aging is challenging the fiscal sustainability of public pension and health care systems in the region. Policymakers will need to ensure adequate benefits for the rising share of older people—notably their social acceptability—by supporting formal employment and gradually reforming pension and healthcare systems.

Demographic dividend

Latin American countries are still younger than most advanced economies, but population aging is expected to accelerate. Today Latin American women have on average a little more than two children per woman. That is three times fewer than in 1950! Even in Guatemala and Bolivia, the two countries in the region with the highest fertility rates, the number of children per woman has started to fall rapidly. At the same time, people are living longer.

Rising living standards and better access to quality health care have increased the life expectancy of Latin Americans to close to 75 years. Chileans and Costa Ricans can expect to live more than 80 years, slightly longer than United States residents.

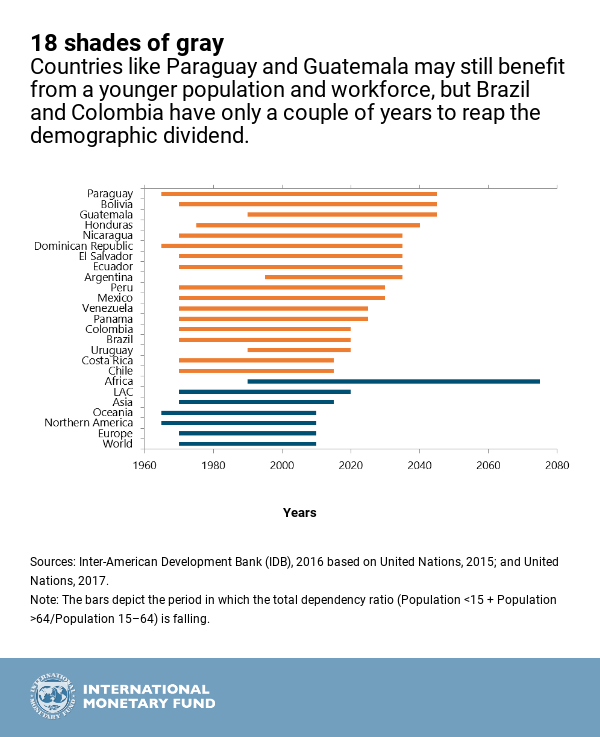

The combination of fewer children and older adults is putting an end to the demographic dividend that Latin America has been enjoying since the 1970s—that is the period during which the population aged between 15 and 64 grows faster than the population younger than 15 and older than 64. Its end implies there are fewer active people to support a growing number of dependents.

Countries with the youngest populations like Paraguay, Bolivia, and Guatemala may still benefit from the dividend until 2045, but Uruguay, Brazil, and Colombia have only a couple of years of dividend left, while the dividend is already over in Chile and Costa Rica.

Pension Spending: Trade-offs on the Rise

Thanks to their younger populations, Latin American governments are still spending comparatively little on pensions: less than 4 percent of GDP on average compared to about 9 percent in high income countries and emerging Europe. But, as populations age, public pension spending in the region is projected to increase steeply and narrow the gap with the advanced world.

Countries with unfunded defined-benefit pension systems—where current workers pay for the pension of current pensioners and the government guarantees a certain level of pension benefits—are projected to experience higher increases in their pension bill, as the population ages. In a few countries in the region, a generous mix of high benefits and insufficient workers’ contributions may result in unsustainable financing gaps that would add to public debt burdens if reforms are not made.

On the other hand, countries that are transitioning to a funded defined-contribution system—where each worker sets aside pension savings during his working life, and pension benefits depend on the accumulated contributions and financial returns on those—will experience lower (or even negative) increases in public pension spending, and low or no financing gaps . However, lower increases in public pension spending tend to be associated with low benefits or narrow pension coverage of the elderly.

For example, in the Dominican Republic, Mexico, Bolivia, Chile, and El Salvador, pensioners receive benefits well below the average in other countries.

In the Dominican Republic and El Salvador less than 20 percent of the elderly population receive a pension, with different combinations of contributory and non-contributory benefits.

Low levels of coverage and benefits could be perceived as inadequate and became socially unsustainable, ultimately resulting in higher fiscal liabilities if they create political pressure for the government to extend coverage, or top up pension benefits.

Hence, there is an important trade-off between financial and social sustainability when it comes to future pension spending.

Narrow coverage and insufficient benefits are largely a result of the high level of informality and low participation of women in labor markets in Latin America—on top of high commissions and low financial returns that depress benefits worldwide.

They also exacerbate income and gender inequality because low-income workers are less likely to receive a pension or, if they do, are more likely to receive a sub-par one. Moreover, women tend to have lower coverage and benefits than men due to: (i) lower participation in the labor market, (ii) fewer years of salaried work due to childbearing, (iii) lower wages, (iv) earlier retirement ages, and (v) longer life expectancy, resulting in higher old-age poverty among women.

Health Care: Getting Costlier

Spending by governments on health care in Latin America is much higher than it was two decades ago, as many countries have embarked on efforts to increase coverage and reduce inequities.

Currently, public health spending in the region averages 4.4 percent of GDP, which is relatively high given the region’s current demographic profile. For the average person, medical costs escalate later in life, which means that, as the share of the population ots, which result in better, but costlier, services for patients.

Our projections show that, given this starting point and the projected pace of population aging, public health expenditure as a percentage of GDP in Latin America could reach the levels of advanced countries by 2100. In fact, in the absence of reform, Latin America is projected to experience the largest increase in health care expenditure of any region over the long term.

Lessening the impact

This long-term prognosis may seem overwhelming. However, the good news is that promoting the labor force participation of women and the elderly, fostering formalization, and gradually reforming pension and healthcare systems can help moderate the impact of aging on government accounts while preserving equitable access to health services and adequate pension benefits.

For pension systems, raising retirement ages and contribution rates, especially in countries where those are comparatively low, and reducing benefits in countries with excessively high pension entitlements, will help build buffers and pay for future increases in pension expenditures associated with aging. These reforms would need to be carefully designed to avoid discouraging formal employment. To manage health spending growth, while preserving health outcomes, countries should pursue efficiency-enhancing reforms while expanding access to basic healthcare services when coverage is low.