The global financial crisis a decade ago and the resulting recession left long-lasting scars on future growth in more ways than one.

Our October World Economic Outlook points to signs that the crisis may have had lasting effects on potential economic growth through its impact on fertility rates and migration, as well as on income inequality.

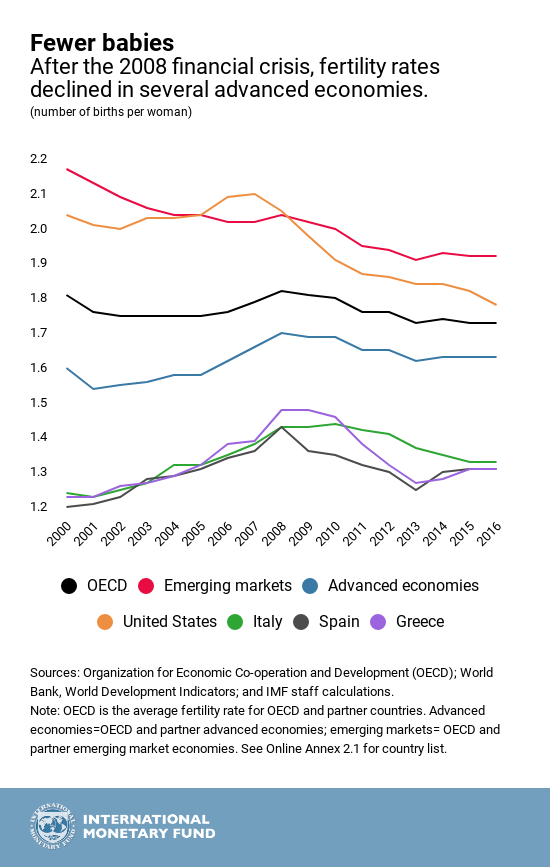

Our chart of the week shows that in the decade before the crisis, the fertility rate—the number of children each woman is expected to have in her lifetime—rose in several advanced economies, only to decline afterward.

The crisis may have had lasting effects on potential economic growth through its impact on fertility rates and migration.

In the United States, the rate fell from a peak of 2.12 in 2007 to 1.8 in 2016. For European countries, such as Greece and Spain that suffered a double-dip recession, the fertility rate decreased from 1.5 to about 1.3 over the same time period.

Evidence from Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries shows that employment losses were the most important channel through which the crisis affected fertility rates. Other studies find that complex social changes—such as higher women’s participation in the workforce and a desire for smaller families—as well as cuts to welfare systems could affect women’s decisions about family size.

The persistently low birth rates over the past decade will slow the growth rate of the labor force of the future in these countries, which will weaken potential output growth. And, if immigration were to decline, fewer babies will exacerbate the already aging and shrinking populations of many countries.

Policymakers in some advanced economies will need to tackle this trend and find ways to encourage women to have children. For example, increasing access to affordable and high-quality childcare, family-friendly labor laws, and tax policies that do not penalize secondary earners can make it easier for families to have more children.