(Versions Español and Português)

Public finances in most Latin American countries strengthened significantly before the global financial crisis. Since 2009, countries have generally increased public deficits, drawing down on their fiscal coffers.

These expansionary policies continue and are yet to be reversed. With further pressures likely to build over the period ahead—as economic growth has slowed, commodity prices have softened, and external funding costs are bound to rise—now is the right time to rethink fiscal policies across the region.

Significant progress

Latin America’s public finances have strengthened in many ways over the past ten years.

Latin America’s public finances have strengthened in many ways over the past ten years.

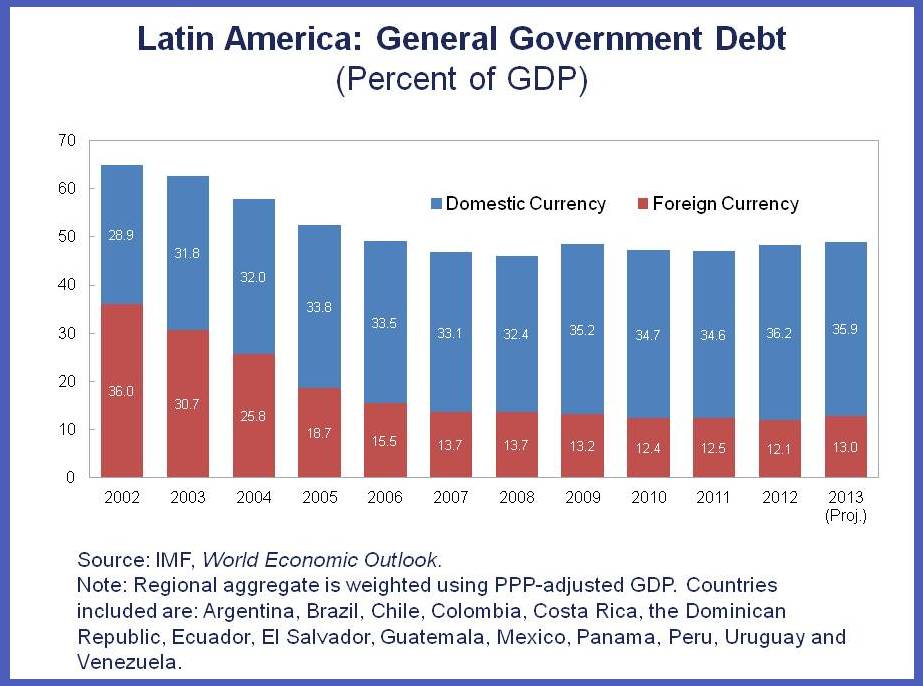

- Government debt ratios declined by 16½ percentage points on average between 2002 and 2012, reflecting rapid GDP growth, falling interest costs, and solid primary surpluses in the first half of the period.

- The average maturity of debt outstanding has increased, reducing rollover and interest rate risks.

- Countries have further overcome the so-called ‘original sin’, which described a strong historical dependence on external funding in foreign currency. In all of the financially integrated economies, debt issuance has shifted decisively toward local-currency bonds, lowering exchange rate risk.

Better fiscal outcomes have been supported by stronger institutions, as several countries—including Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru—have introduced or strengthened their fiscal responsibility frameworks since 2000.

But more challenging times ahead

Yet, governments have also been helped by exceptionally favorable external conditions. Commodity exporters benefited from a sustained surge in global commodity prices, which boosted export earnings, domestic growth, and government revenues. From 2002 to 2008, fiscal revenue in the region grew from below 26 percent to above 30 percent of GDP. In addition, the marked fall in global interest rates reduced average government interest bills by almost 2 percentage points of GDP over the course of the decade.

Yet, governments have also been helped by exceptionally favorable external conditions. Commodity exporters benefited from a sustained surge in global commodity prices, which boosted export earnings, domestic growth, and government revenues. From 2002 to 2008, fiscal revenue in the region grew from below 26 percent to above 30 percent of GDP. In addition, the marked fall in global interest rates reduced average government interest bills by almost 2 percentage points of GDP over the course of the decade.

The increase in revenue and decline in interest expenses improved fiscal balances, even as primary government spending soared. The greater fiscal space also allowed policymakers to mount a strong countercylical response to the global financial crisis, for the first time in the history of Latin America.

However, these expansionary policies have proven hard to reverse, with public expenditure significantly outpacing revenue since 2008. Looking at the entire period from 2002–12, primary expenditure has climbed from 24½ percent to 30 percent of GDP on average across Latin America. Increases were particularly large in Argentina, Ecuador, and Venezuela, where the ratio of primary spending to GDP surged by 12-23 percentage points. As a result, fiscal balances are now significantly weaker than prior to the global financial crisis in most countries.

However, these expansionary policies have proven hard to reverse, with public expenditure significantly outpacing revenue since 2008. Looking at the entire period from 2002–12, primary expenditure has climbed from 24½ percent to 30 percent of GDP on average across Latin America. Increases were particularly large in Argentina, Ecuador, and Venezuela, where the ratio of primary spending to GDP surged by 12-23 percentage points. As a result, fiscal balances are now significantly weaker than prior to the global financial crisis in most countries.

No case for fresh stimulus today

With economic activity slowing and external tailwinds turning into headwinds, how should fiscal policy respond?

From a cyclical perspective, even though growth is moderating, output levels are still close to potential. Tight labor markets, infrastructure bottlenecks, and the continued widening of current account deficits all point to limited spare capacity. Therefore, it is hard to argue that more fiscal easing is needed. Indeed, as the previous stimulus has never been properly reversed, launching a new stimulus now would undermine its credibility as a countercyclical tool. And even if activity were to ease a bit further, monetary policy is better suited to respond to a normal cyclical slowdown.

Crucially, some of the ongoing growth slowdown may be structural in nature. Research done at the IMF suggests that potential growth rates in the region are coming down (see Chapter 3 of the May 2013 REO). Growth of physical capital is expected to moderate, reflecting the expected normalization of external financing conditions and the stabilization of commodity prices. Employment growth is also likely to be limited going forward—labor participation rates are already elevated, and unemployment has fallen to record lows. Thus, unless total factor productivity growth picks up, output growth is likely to stay below the rates observed over the past decade. In this environment, attempts to maintain unrealistically high growth targets through fiscal stimulus would merely weaken public finances.

Conversely, maintaining strong fiscal balances will put governments in a better position to buffer the impact of future headwinds, such as rising real interest rates and a possible decline in global commodity prices. It will also help address current imbalances, including widening external current account deficits and persistently high inflation in some countries. Taking a longer perspective, prudent fiscal policy today will provide a strong foundation to meet the future challenge of population aging.

After a long period of continous increases in public spending, now may also be a good time to launch a thorough expenditure review that looks for ways to increase efficiency and reduce wasteful or untargeted expenditure.

Overall, prudent policy choices today are critical to preserve the gains in fiscal stability that have been achieved over the past decade, and to lay the basis for continued prosperity.