Typical street scene in Santa Ana, El Salvador. (Photo: iStock)

IMF Survey : Monetary Policies in Advanced Economies: Good for Them, Good for Others

July 23, 2015

- Actions to close output gaps in advanced economies will help other economies too

- Emerging markets more resilient than in the past to effects of dollar appreciation

- Corporate debt buildup in emerging markets bears watching

Accommodative monetary policies in systemic advanced economies can have a positive impact on economic activity in other countries if they are perceived as good news about growth prospects in advanced economies, according to a new IMF analysis on the “spillover” impact of policies on other economies.

“Now Hiring” sign in window of retailer in New York City. Closing output gaps in advanced economies will reduce their unemployment and also help other countries (photo: Richard Levine/Demotix/Corbis)

Multilateral Surveillance

Seven years after the onset of the Great Recession, economic activity in many advanced economies remains below potential. In the euro area, for example, the output gap—how far output is below where it could be if all productive resources such as labor and capital were being fully utilized—is nearly 2½ percent.

Central banks in the so-called systemic advanced economies—the euro area, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States—have responded with monetary policies that should help close output gaps. The IMF staff estimates that the euro area output gap will decline from nearly 3 percent in 2014 to about 1 percent in 2017. In Japan, the output gap, which was more than 1½ percent in 2014, is expected essentially to close by 2016.

The closing of output gaps, in turn, will help lower unemployment and raise investment in these economies, as the IMF’s First Managing Director, David Lipton noted recently. But what impact will these policies have on other economies? This was the focus of the 2015 Spillover Report.

Good for others

There are fears expressed in some circles about the adverse impact on other economies of an increase in interest rates in advanced economies as they start to recover. The report, however, finds that closing output gaps in systemic advanced economies will on balance be good for other economies. Why interest rates are rising in advanced economies proves to be critical. If interest rates are going up because of improved economic prospects in these economies, that turns out to be beneficial for other economies. As advanced economies recover, they will increase their imports from other countries, providing a boost to those economies, offsetting the tighter financial conditions.

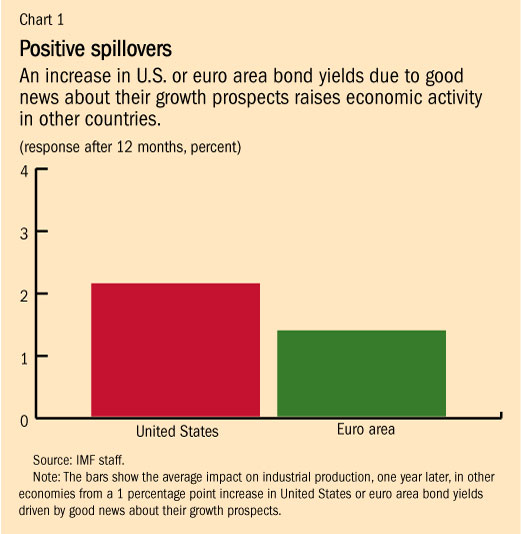

As Chart 1 shows, a 1 percentage point increase in bond yields in either the United States or the euro area because of improved growth prospects leads to substantial increases in industrial production in other economies in the year following the increase. In short, good news about U.S. or euro area growth is good for others. These positive spillovers are amplified when there is good news about growth in both the United States and the euro area and dampened when there is good news about one but not the other.

A Background Note issued with the report shows that if advanced economy interest rates rise for reasons other than improved growth prospects, this could be associated with lower economic activity in other economies. However, since monetary policy actions are expected to close output gaps (i.e., improve growth prospects), the likely scenario is the one shown in Chart 1.

Greater resilience to strong dollar

Differences in monetary policies among systemic advanced economies, together with changes in expectations about growth, have been reflected in exchange rate movements, notably a sustained appreciation of the U.S. dollar during 2014. Past episodes of sustained dollar appreciation have been associated with crises in emerging markets (for instance, during 1980–85 and 1995–2001). Could past be prologue? The report suggests reasons to hope otherwise.

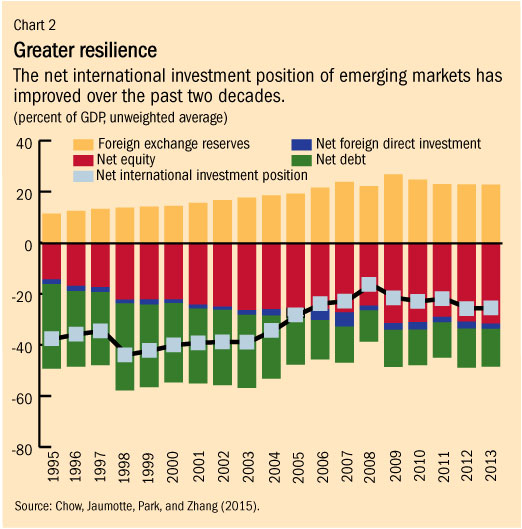

Since the mid-1990s, the net international investment position (that is, the value of foreign assets owned by a country’s public and private sectors, minus the value of assets in that country owned by foreigners) of emerging markets has improved considerably (Chart 2), making them less vulnerable to changes in currency movements. Emerging markets have also been able to reduce their dependency on debt, and their debt is increasingly in domestic rather than foreign currencies.

A second Background Note, however, points out some reasons not to be sanguine. Although net positions have improved, large gross amounts of debt in foreign currencies could still make countries more vulnerable to rollover and interest rate risks. Domestic-currency external debt, though not vulnerable to exchange rate changes, is also not without risk. Finally, although overall exposures to foreign exchange risk have decreased in most cases at the country level, corporate sector exposures have picked up considerably.

Corporate debt buildup

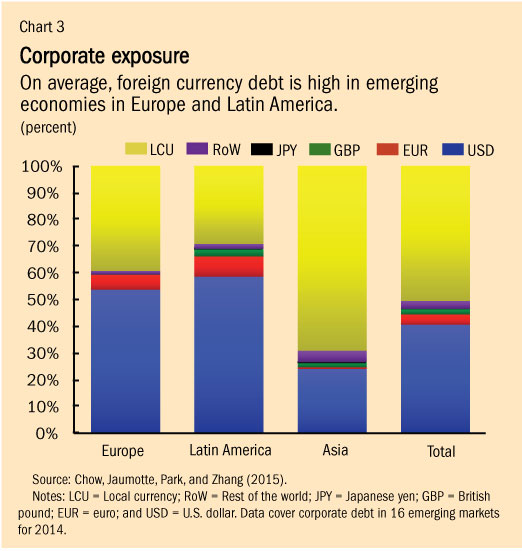

Corporate debt denominated in foreign currencies has risen substantially, particularly on average in emerging markets in Latin America and Europe (Chart 3). However, an assessment of the risks from this buildup has to account for a number of factors:

• Hedging: Countries are more vulnerable to U.S. dollar appreciation if they have large amounts of dollar debt while their income streams are mostly in other currencies. Though firms in such countries may be actively hedging this risk, data limitations make the extent of hedging hard to quantify.

• Sectoral differences: Though sectors such as utilities and real estate tend to have lower foreign-currency debt than others, they also generate less income in foreign currencies, and hedging is rather uncommon in these sectors. Hence countries where such sectors loom large may be more vulnerable to exchange rate movements.

• Maturity structure: Over time, the composition of countries’ debt has shifted from bank loans to corporate bonds. The fairly long-term maturity of these bonds makes them less vulnerable to developments such as the U.S. dollar appreciation.

Overall, the report suggests that corporate sector risks remain moderate at present but have risen and bear watching.