Typical street scene in Santa Ana, El Salvador. (Photo: iStock)

IMF Survey: Bouncing Between Floors? Globally, House Prices are Up and Down

October 8, 2010

- House prices still bouncing along the bottom in many countries

- Policymakers in Asia taking measures to cool housing markets in their countries

- Problems in housing markets slowing economic recovery

Real estate markets have been a source of strength during past economic recoveries, but this time is different, according to IMF research.

There are renewed fears of a double-dip in the U.S. housing market (photo: Newscom)

World Economic Outlook

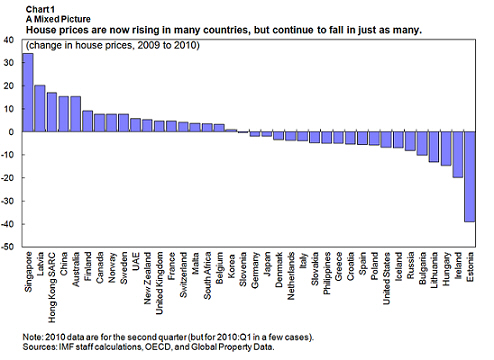

While house prices have rebounded in many countries from a year ago, in just as many prices continue to fall or are only gradually stabilizing (see Chart 1). In a few countries, including the United States, there are concerns of a “double dip” in the housing market.

“Double dip” in U.S. housing markets?

In the United States and the United Kingdom, tax measures temporarily increased housing activity, but demand fell and prices receded after the recent expiration of these incentives.

In the United States, the limited success of mortgage modification programs and the shadow inventory from foreclosures and delinquencies has renewed fears of a “double dip” in its real estate market. How large is the shadow inventory? Adding together the number of homes already in foreclosure, those at risk of foreclosure because owners have been in default for 60 days or more, and possible strategic defaults if house prices decline, the shadow inventory of houses for sale may reach 7 million. This is ten times the historical absorption rate of 700,000 units a year in the U.S. housing market.

There are other problems. Delinquency rates on commercial mortgage-backed securities have recently reached record highs, and considerable amounts of commercial real estate debt will become due over the next few years. Resets on adjustable-rate loans loom on the horizon. And problems in the housing market and the labor market are intertwined: U.S. states where the house price bust was more pronounced are also where employment has fallen the most (see Chart 2). This reflects the importance of the construction sector in many states, as well as workers’ reduced ability to move to other states when the equity values of their homes have taken a hit.

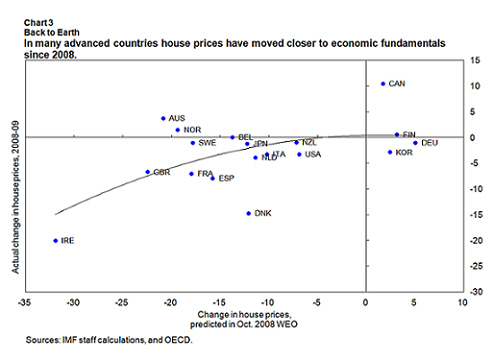

That said, house prices in the United States and other advanced countries have already undergone substantial corrections since 2008. So in most countries, house prices have moved much closer to their economic fundamentals (see Chart 3). Our econometric estimates indicate that if the remaining adjustment were to happen over five years, house prices would fall modestly—an average annual rate of between 0.5 percent and 1.5 percent.

Rebound in Asia-Pacific?

Several economies in the Asia-Pacific region, Canada, and most Scandinavian countries have experienced a rebound in real estate prices and residential investment since 2009. Will this rebound continue?

In many of the advanced economies in this group, current price-to-rent and price-to-income ratios are still above historical averages, and econometric estimates still show a deviation of house prices from fundamental values.

For the emerging market economies in this group (namely, China, Hong Kong SAR, and Singapore), economic fundamentals—mainly, strong growth prospects—appear to provide more support for the observed house price increases. But the econometric estimates are less reliable for these economies than for the advanced economies because data are available for only a fairly short period. More anecdotal evidence—reports of speculative activity, rising vacancy rates in commercial property, sizable mortgage credit growth, and massive capital inflows, especially in China—suggest that these real estate markets may be overheating. In China, deviation of house prices from fundamentals is estimated to be higher in Beijing, Nanjing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen than in other cities.

Some governments in the region have taken measures to tame real estate markets. The Chinese government deployed a range of regulatory tools in the spring of 2010, including increases in transaction taxes and stricter controls on lending.

Slowing the economic recovery

In many countries, the impact of the housing correction on the economy is likely to be prolonged because households are trying to shed debt acquired during the boom. But households shed debt at a much slower pace than the corporate and financial sectors: the largest item on most household balance sheets is real estate, which is more difficult to sell off in a fire-sale than bonds and equities. Therefore, the recovery is likely to be slower than in some past recessions—such as the one which followed the bursting of the dot.com bubble a decade ago—which were triggered by problems in corporate balance sheets.

For countries such as Spain and Ireland there is an additional reason to expect slow recovery. In these countries, the construction sector grew much more rapidly than other sectors of the economy and became the engine of growth. The housing bust has thus brought severe contraction in construction output and employment. The unemployment rate is now three times its 2000–07 average in Ireland and twice its 2000–07 average in Spain, compared with a 20 percent increase on average among euro area countries.

Bottom line

In contrast to past recoveries, there appears to be little hope for a sustained upside boost to the overall economy from the real estate sector. In economies where real estate markets are still in decline, the drag on real activity will continue. And in economies where house prices and residential investment are rebounding, concern about bubbles is eliciting policy actions that will temper any short-term boost to economic activity.