Fiscal policy in advanced economies: fiscal adjustment, efficiency and growth

March 13, 2012

At the Milan Catholic University

March 13, 2012

| View the presentation (pdf) on the Fiscal policy in advanced economies. |

Today I will discuss the complex relationship between economic growth and fiscal policy. It is a complex relationship because it involves various kinds of feedbacks between the two sides of the equation, and different effects depending on whether we look at the short or the long run. But it is an issue of extreme importance for policy-makers in advanced countries. Fiscal policy has critical implications for economic growth both in the short and the long run. At the same time, strong growth greatly facilitates fiscal adjustment, both in the short and in the long run. And fiscal adjustment is what most advanced countries need over the coming years, as their public debt to GDP ratio stands at an historical peak reached only once in the last 130 years.

To navigate through these complex interactions, we need a map and here is the map of my presentation. I will discuss first the short-term interactions between growth and fiscal policy and then look at the longer term interactions, drawing in each case some policy conclusions.

Let me start with the short run and see how fiscal tightening affects growth.

There are two main channels.

The first arises because a weak fiscal stance can lead to a fiscal crisis. The fiscal crises that have hit countries with poor fiscal accounts recently in Europe are a reminder of how powerful these effects are. Having weak fiscal accounts may not be a sufficient condition to be in trouble but it is a necessary condition—except in cases of pure contagion, which I believe are very rare. I think most economists would agree on this.

The second channel goes through aggregate demand and arises because fiscal tightening leads to lower aggregate demand. This is perhaps more controversial. You know the standard Keynesian view that fiscal tightening leads to a slow down of economic activity. As you know, others have argued that expansionary fiscal tightening does exist, especially if fiscal tightening that is focused more on spending cuts rather than tax increases. I think there are indeed cases in which a sharp tightening of fiscal policy is accompanied by a fiscal expansion. However, a recent paper by Roberto Perotti has shown that the output expansion, in these cases, typically reflects an exchange rate depreciation and a relaxation of monetary conditions rather than confidence effects per se arising from the fiscal tightening. Thus, in the absence of an independent exchange rate or monetary policy, which is the case of euro area countries for example, fiscal consolidation is likely to be accompanied by lower economic growth. Even with an independent monetary policy, the most recent work done by the IMF (Chapter III of the Fall 2010 World Economic Outlook of the IMF) shows that fiscal multipliers during fiscal contractions are likely to be positive on average. Even more recent work which will be published in the forthcoming IMF Fiscal Monitor will show something that theory predicts but that surprisingly has been ignored by much of the recent VAR literature on multipliers, namely that multipliers are larger when output is below potential, as in the current cases of many advanced economies.

You may have noted that these two channels operate in different directions. The first implies that not enough tightening could be bad for growth. The second implies that too much tightening is bad for growth. This suggests that you need to balance these effects and that fiscal policy must be just right.

However, one could argue that a short-term deceleration in economic activity is the price to pay to strengthen public finances and, therefore, avoid even bigger problems later on. But things are not so simple because of feedbacks from growth to the fiscal accounts. Three channels are particularly important.

The first one is the most standard one: a deceleration of growth reduces tax revenues and increases spending for unemployment benefits, the so called automatic stabilizers. This implies that, if I tighten fiscal policy by one percent of GDP, the actual improvement of the deficit is smaller by an amount that depends on the automatic stabilizers (as well as on the fiscal multiplier). This chart illustrates for various countries the relationship between discretionary tightening and actually decline in the deficit to GDP ratio arising from the operation of the automatic stabilizers, assuming a fiscal multiplier of 1 with respect to the initial discretionary tightening. On average for advanced countries a one percentage point of GDP reduction in discretionary spending leads to 0.7 percentage point reduction in the deficit. The deficit declines, but by less than the discretionary tightening. But at least does decline.

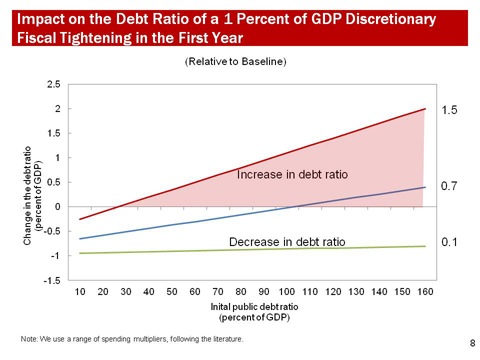

The second channel relates to the effect of fiscal tightening on the public debt to GDP ratio, another key fiscal indicator. The debt ratio is likely to rise, in the year when fiscal policy if tightened, if the fiscal multiplier is high and the initial stock of debt is high. The reason is that, when you tighten fiscal policy, debt, the numerator of the ratio, declines, but declines less in percentage terms if the initial debt stock is high. Moreover, GDP, the denominator of the ratio, also declines and declines more if the fiscal multiplier is high.

This chart (Slide 8) shows you the effect on the debt ratio of a one percentage point discretionary tightening, for various initial levels of the debt ratio and for various fiscal multipliers (as well as for average automatic stabilizers). As you can see, you can easily get a combination that yields an increase in the debt ratio when fiscal policy is tightened. And this is more likely to happen when the debt ratio is initially high.

Is this a problem for a fiscal adjustment strategy? Not necessarily. The debt ratio increases in the first year but then starts declining as the deficit is moved to a permanently low level. But, if financial markets focus on the behavior in the short run of the debt ratio they may respond negatively to a rise in the debt ratio.

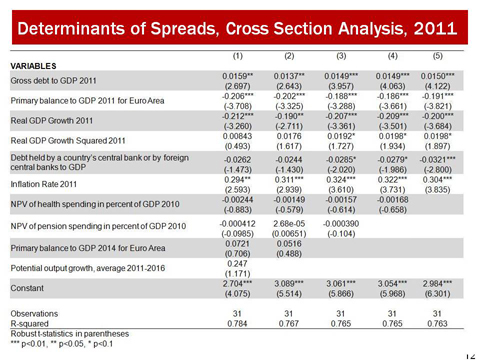

The third feedback of growth to the fiscal accounts arises because markets may get worried because of the deceleration of growth. Given a certain debt and deficit ratio, high growth countries typically pay low interest rates, because these countries are seen as being able to “grow out” of their debt. And this is confirmed by this chart in which CDS spreads in 2011 are plotted against the growth rate in the same year. This focus on short-term growth is somewhat puzzling because in principle it is long-term potential growth that affects fiscal sustainability, not short-term growth. And yet, there is no clear relationship between spreads and long-term growth. This focus on short-term growth could, however, be explained by political economy considerations: markets believe that a country where GDP is declining a lot would not sustain its fiscal adjustment effort over time.

We found evidence of this effect of short-term growth on interest rates on public debt in some econometric estimates that we run recently and that I would like to share with you. I would like you to focus on the last column (Slide 12), which includes my preferred specification. On the left hand side of the equation you have the 5 year CDS spread in the first 9 months of 2011. On the right, you have the primary balance to GDP ratio and the debt ratio, the fiscal fundamentals, and they have the right sign: higher primary balances lower the spreads; higher debt increases the spread. Then you have growth which enters in a non linear way. The nonlinear specification and the signs of the coefficients imply that lower growth increases the spread, and that the increase per unit of tightening is larger as growth declines. Markets get increasingly worried as growth enters low/negative territory.

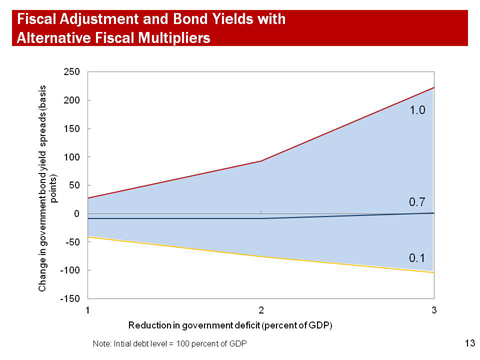

There are other variables in the regressions. But let me focus on the interaction between fiscal tightening, growth and spreads that can be derived from this equation. This chart (Slide 13) shows for various levels of the fiscal multiplier (on the right hand side) and for various levels of fiscal tightening (on the horizontal axis) the impact on spreads. This takes into account both the fact that the debt ratio may increase when you tighten fiscal policy and the fact that lower growth is accompanied by higher spreads. And, as you can see, if the fiscal multiplier is sufficiently large and if the fiscal tightening is sufficiently strong you end up in negative territory: fiscal tightening is accompanied by higher spreads.

This possible increase in interest rates when fiscal policy is tightened is a problem for the sustainability of a fiscal adjustment strategy, not only because higher interest rates increase the deficit, but also because of a key political economy reason: if painful fiscal tightening is accompanied by early evidence that it is working, the adjustment is more easily sustained. But if markets do not reward the effort, the resolve of the government to carry on the fiscal adjustment may be undermined.

What are the policy implications for the way fiscal adjustment should be conducted arising from these complex interactions between fiscal policy and growth?

First: countries that are not under pressure and have fiscal space should decide the pace of fiscal adjustment also in light of cyclical considerations. As I said, insufficient tightening is bad, but, particularly in the current phase of uncertainty about the recovery, we see risks arising from frontloading the adjustment. Fiscal adjustment should be just right. What matters is steady progress.

Second: to ensure that gradual fiscal adjustment is not mistaken for lack of fiscal commitment, countries should define clear medium-term adjustment plans that anchor the evolution of public finances over the medium term. Most countries have done so but not the two largest advanced economies, the United States and Japan.

Third: some countries that are under pressure will have to undertake—indeed are undertaking—frontloaded fiscal adjustment measures. This is inevitable for a number of reasons ranging from lack of adequate financing at reasonable rates, to political constraints. Even so an adjustment strategy centered exclusively on fiscal tightening would be less likely to work. One key reason is the feedback loops between growth and fiscal tightening that I mentioned earlier: if frontloaded fiscal adjustment is accompanied by a decline in growth, interest rates may not decline. What is needed to complement fiscal adjustment is the availability of adequate financing to keep interest rate down while the effects of the adjustment on the fiscal accounts materialize. It is in this context that we have argued Europe needs to put in place stronger firewalls.

Let us move to the long-term interactions between growth and fiscal policy.

Fiscal policy has key implications for potential growth. They operate through both macro and micro channels.

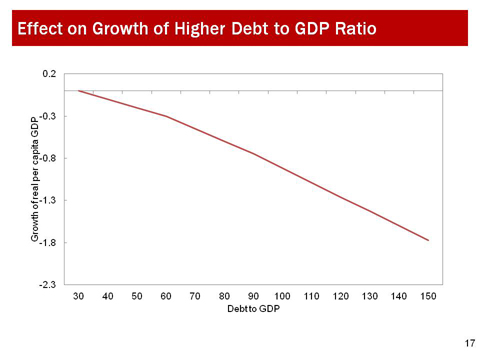

Let me start with the macro channels. There is by now a consistent body of literature that finds significant effects of high public debt on potential growth. This includes work by Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff, by Stephen Cecchetti and others, and by Kumar and Woo, from the Fiscal Affairs Department of the IMF. This work finds that, at least beyond a certain threshold—which is similar in the three studies that I quoted at about 80-90 percent of GDP—higher public debt lowers potential growth.

This chart (Slide 17) reports how much GDP growth would decline as public debt increases, based on our own estimates. The average elasticity is that an increase by 10 percentage points of the debt to GDP ratio lowers potential growth by about 0.17 percent. So the difference in potential growth between having a debt ratio of 120 percent of GDP and a debt ratio of 60 percent of GDP is about one percentage point. Our work shows that high debt is accompanied by lower growth because of the usual crowding out effects: private investment would be lower and, hence, productivity growth would be lower. Italy and Japan, two high debt-low growth countries, are good examples of this kind of effects.

Looking ahead, it is a cause of concern that the share of GDP produced by countries with high debt has increased from 19 percent in 2007 to 81 percent in 2010. This suggests that advanced countries will grow less if debt is not brought down over the medium term.

Let me turn now to what I called the micro effects of fiscal policy on growth. By this I mean the way the presence of the public sector is felt in the economy over and beyond its macro balances (deficit and debt). The overall tax pressure, the way tax revenues are levied, the way in which spending takes place affects investment, employment, economic efficiency and growth.

Once again, the issue is complicated and it does involve tradeoffs. For example, public policies that tend to be less distortive enhance economic efficiency. They may also not be conducive to a more equitable income distribution. And many believe that growth that benefits only a few is not sustainable (as for example developments in the Middle East have recently shown).

It would take me too long to deal with these issues in any detailed way, but let me give you a flavor of how we look at them at the IMF.

I will start from our views on revenues and growth, and then move to the spending side.

First, the overall tax pressure, as measured by the tax to GDP ratio: we are not dogmatic about this but we have definitely argued on several occasions that when tax and contribution rates are already as high as they are in continental Europe economic growth would benefit from lowering them. At the same time, we have argued that, in countries where they are relatively low like Japan and the United States, the magnitude of the existing fiscal imbalances is such that addressing it just through spending cuts would require cutting not only nonproductive spending but also productive spending. Indeed, a recent paper produced by my department (written by Baldacci, Gupta and Mulas-Granados) shows that fiscal adjustment that relies only on the spending side is less successful when the adjustment need is large.

Second, when it comes to the composition of revenues, taxing consumption leads to lower distortions than taxing income. In particular, we have recently argued that, countries that are facing competitiveness problems can benefit from a shift from labor taxation to VAT (what we call “fiscal devaluation”). At the same time, we have argued that effects on long-term growth coming from such a switch should not be overestimated. They are likely to be large only when, as a result of nominal wage rigidity they lead to a decline in real wages from a disequilibrium position. Econometric work in this area done by my department includes a recent paper by Michael Keen and Ruud de Mooij.

Third, we have argued that a good way of raising revenues while reducing distortions is to eliminate the so-called tax expenditures, those preferential treatments of certain sectors or activities that distort economic choices. In particular, an issue that we have raised repeatedly is the existence of multiple VAT rates, with lower rates typically on goods and services that are supposed to be consumed more by the poor, like food and clothing. This has been very controversial as it seems to go against our line that equity is a legitimate goal for fiscal policy and one that, as I mention, could perhaps enhance long-term growth. However, while these goods as a percentage of income are consumed more by the poor, in absolute terms they are consumed more by the rich. This means that by removing these lower VAT tax rates it would be possible to raise revenues in a way that allows not only a reduction in the deficit but also an increase in support to the poor through targeted spending.

Fourth, we have called for raising taxes aimed at correcting externalities. These have traditionally included carbon taxation and, more recently, taxes on the financial sector, the externalities arising from excessive risk taking, leading to systemic risk (although we favor a VAT-like tax on financial institutions rather than a financial transaction tax).

Fifth, we have called for taxing property, particularly real estate as taxing less movable tax bases is less distortionary.

Finally, we have called for increasing the fight on tax evasion, again something that is important not only from an equity perspective, but also as a way to reduced distortion between activities in which evasion is easier and activities where it is more difficult.

We have not tried to quantify the effects of a better structure of taxation on potential growth, but we have computed that it would be possible to raise revenues by several percentage points of GDP—at least three in the average of advanced countries—through a combination of cuts in tax expenditure, externality-reducing taxation, property taxation and reduction in tax evasion.

Let me move to the spending side. Here we have argued that cuts across the board are not conducive to durable adjustment and to growth. Spending reviews—as done for example in the United Kingdom—should be used to identify the spending programs that are working and should be protected, and those that are not working and should be cut. So the proper spending mix would have to be country specific, including in assessing the right level of public investment. I priori, however, we have identified some sources of spending that should be subject to particular scrutiny. These include:

- Subsidies of various kinds, including agricultural subsidies, with subsidies averaging about 1 percent of GDP in the OECD and rising to 2 percent or more in Austria, Belgium, Denmark and Switzerland.

- Military spending which have increased since 2000 by about 1 percentage point of GDP in the average of advanced countries.

- Spending for public sector wages, which has increased in several advanced countries faster than private sector wages during the ten years before the crisis.

- Social welfare programs that are not mean tested. In the OECD, less than 10 percent of this spending is means tested.

- I list as the last item spending for pension: I list this separately because demographic and other pressures will imply that, for many countries it will be difficult to cut spending in percent of GDP in these areas, although not impossible. With the new round of pension reforms introduced in Italy, pension spending is projected to fall in Italy in the next twenty years. Increasing the retirement age is regarded to be particularly growth-conducive as it leads to increases in the labor force over the medium term.

So, fiscal policies are important for growth. Growth is even more important for fiscal sustainability.

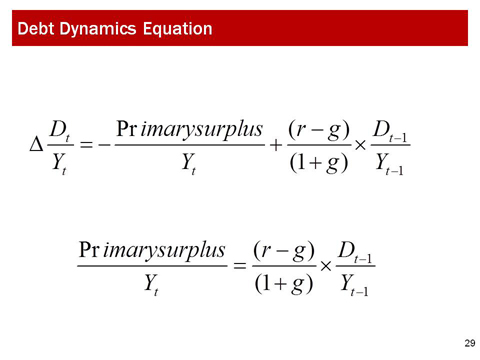

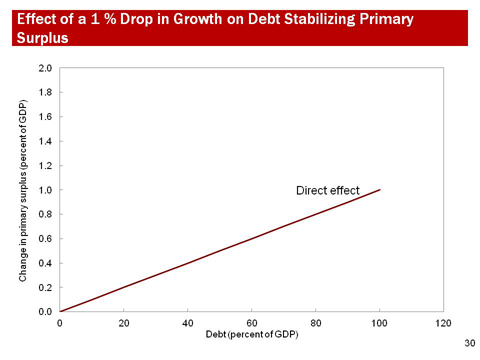

The link between fiscal sustainability is highlighted by the basic debt dynamics equation, which, in continuous time, is reported in this slide (Slide 29). Growth erodes the debt to GDP ratio, a key indicator of fiscal sustainability as we have seen. If we solve this for the debt-stabilizing primary surplus we find that the primary that needs to be maintained is a decreasing function of the growth rate. Here I would like to underscore that growth is particularly important for high debt countries, as it enters this equation multiplied by the initial debt stock. This chart (Slide 30) reports the effect on the debt-stabilizing primary surplus of a one percentage point decline in potential growth as a function of the debt level. So for example, if your debt ratio is 40 percent of GDP, a one point loss in potential growth requires an increase in the primary balance of 0.4 percentage of GDP. But if your debt is 100 percent of GDP, the primary must improve by 1 percentage point.

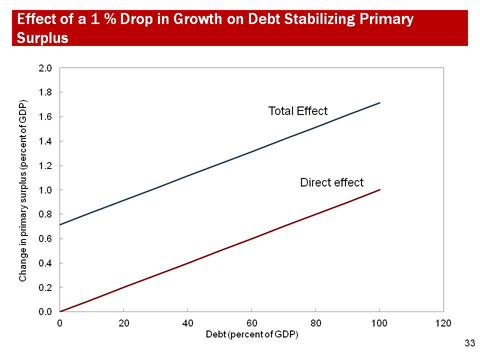

This however underestimates largely the effect of strong growth on debt sustainability. The reason is that the primary balance itself is affected by growth. This is of course obvious from a short-term perspective, as we have already discussed. But it seems to be true also in the longer run. Now, there is no strong theoretical reason why the primary balance, expressed in percent of GDP should be positively correlated to potential growth. And yet, empirically, this seems to be the case.

This is illustrated by this chart which plots the average primary balance observed for any 10-year period against the corresponding average growth rate in the same period. The relationship is clearly positive: stronger growth is associated with stronger primary balances, possibly because spending is adjusted only slowly to stronger growth rates.

This implies that the link between fiscal sustainability and growth is stronger than we may think. If we incorporate the effect of growth in the primary balance reflected in this regression slope (Slide 33), we find that the relationship between increase in growth and need for discretionary fiscal action is no longer described by this line, but by this line. For example, for a debt ratio of 100 percent a one percent increase in growth lowers the primary fiscal need by 1.7 percent of GDP, not just one percent of GDP.

Indeed, if a country managed to save all additional revenues coming from stronger growth, the fiscal adjustment process that is needed in advanced countries would be greatly facilitated. For example, a country that started with a debt ratio of 100 percent, and a tax to GDP ratio of 40 percent, as many countries in Europe, would lower its debt by almost 30 percentage points after 10 years if growth were increased by a single percentage point.

This is not just theory. History confirms that fiscal adjustment rarely occurs without healthy economic growth. In the post-World-War-II period, we have identified 35 episodes in which the debt/GDP ratio was continuously reduced in advanced economies, by at least 10 percent of GDP cumulative. Of these, only one case (Italy between 1994 and 2004) occurred with real GDP growth below 2 percent. Growth does not simply matter through the denominator in the debt ratio. Growth also has an impact on governments’ ability to deliver lasting improvements in the fiscal position, even controlling for the state of the economic cycle. In the post-war era, there were 60 instances in which advanced economies improved their cyclically adjusted primary fiscal balance continuously over three or more years; of these, only a handful occurred with growth below 2 percent.

Let me conclude by looking, once again, at the policy implication of this complex relationship between fiscal policy and long-term growth. I would underscore the following.

First, stabilizing public debt at the high post-crisis levels would penalize potential growth. There is a need to lower public debt over time.

Second, strong medium-term growth is critical for a successful fiscal adjustment process. This means that reforms in goods, service, and labor markets will be important also as a tool to support the fiscal adjustment process.

Third, and consequently, in identifying the structural fiscal reforms to implement fiscal adjustments countries need to take into account their implication on economic efficiency. Not all measures are equally good. On the revenue side, there is a need to reduce tax expenditure, fight evasion, reduce the taxation of labor with respect to consumption, and increase property taxation. On the spending side, non targeted social spending, subsidies, and military spending are good examples of where to start. Equity considerations cannot be disregarded, as growth that benefits only few is not sustainable.

Fourth, and bringing all this together in an optimistic vein, the deep links between potential growth and fiscal policy should allow the initiation of a virtuous circle in which pro-growth fiscal adjustment measures, other structural reforms, and lower debt boost growth and the latter facilitates fiscal adjustment. If this virtuous circle is activated, what seems now an almost impossible task, bringing back public debt below 60 percent of GDP, where median public debt was before the crisis, no longer seems so difficult to achieve.

Thank you very much for your attention.

IMF EXTERNAL RELATIONS DEPARTMENT

| Public Affairs | Media Relations | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-mail: | publicaffairs@imf.org | E-mail: | media@imf.org | |

| Fax: | 202-623-6220 | Phone: | 202-623-7100 | |