US Fiscal Policy and the Global Outlook, Speech by John Lipsky, First Deputy Managing Director, IMF, at the American Economic Association Annual Meetings, Roundtable on "The United States in the World Economy", Denver

January 8, 2011

At the American Economic Association Annual Meetings, Roundtable on "The United States in the World Economy"

Denver, January 8, 2011

As prepared for delivery

| Download slides (292 kb PDF) |

Good morning. I’m delighted to take part in this Roundtable, and to have the honor to appear with such an eminent, productive and distinguished panel. I’d like to address three topics in my brief remarks today: the outlook for U.S. fiscal policy, its impact on the global economy, and how new mechanisms for international policy cooperation hold out the promise of improving global economic balance and delivering stronger and more stable growth.

U.S. Fiscal Policy

Turning first to U.S. fiscal policy, the slow pace so far of economic recovery and weak job creation—despite the wide margin of excess capacity—argues for maintaining supportive monetary and fiscal policies in the very near term. Indeed, expansionary fiscal policy already played a critical role in averting a deeper U.S. recession. According to IMF analysis, fiscal measures contributed about 2 percentage points to GDP growth in 2009, and another one percentage point last year. At the same time, federal debt held by the public has risen from about 36 percent of GDP in 2007 to about 62 percent of GDP in 2010, while prospective debt dynamics have worsened significantly. In the absence of corrective measures, and taking into account underlying fiscal pressures that predated the crisis, debt could reach about 95 percent of GDP by the end of this decade—a level last reached immediately following World War II. Without policy adjustments, subsequently the debt simply would keep rising. From this perspective, the need for urgent action to secure medium-term fiscal sustainability appears to be self-evident.

Given the sluggishness of the recovery, the recent adoption of a new U.S. fiscal package is understandable. The measures likely will boost growth this year by about half a percentage point. Of course, it also will raise the deficit. Maintaining a supportive fiscal policy stance at this time reflects the reality that with policy interest rates near zero, the effectiveness of monetary policy is uncertain. Having said this, the Fed’s latest quantitative easing program—that likely will have only a modest impact on growth—appears nonetheless to have reduced perceptions of downside risks, by reinforcing the Fed’s commitment to preventing an ongoing decline in already-low long-term inflation expectations and to supporting the recovery. Although causality is difficult to demonstrate convincingly, inflation expectations rose notably last August—as reflected in the yields on Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (or TIPS)—after the Fed signaled the imminent prospect of further unconventional easing.

The new fiscal package includes several measures that are likely to help boost aggregate demand, although the package also includes other measures that may be less likely to do so. The extension in unemployment benefits will put cash directly into the hands of those with a high propensity to spend—although that is not the sole justification for such a move. The extension of temporary tax breaks for low and middle-income households also will have a positive impact on spending, although with the well-known limitations of temporary tax measures. Other measures were not as well targeted, and the package entails a sizable increase in the deficit—by about 1 percent of GDP in both FY2011 and FY2012—compared to the IMF’s previous forecast, that already included the impact of some anticipated measures (like not changing marginal tax rates for low and middle-income households).

Despite the expected positive impact on growth, the new measures also will make it more difficult for the United States to meet the commitment made by G-20 members at last year's Toronto Summit to halve the deficit as a percent of GDP between 2010 and 2013. In this sense, the stakes are being raised on the development of credible plans to attain medium-term fiscal sustainability.

Indeed, the challenges facing U.S. public finances should not be underestimated, given the sluggish recovery and the prospect of significant increases in aging and health-related spending.

Nonetheless, it’s important to note that only about one-fifth of the overall increase in U.S. public debt projected by the IMF through the end of the decade—a little over 10 percentage points of GDP—is accounted for by the discretionary fiscal measures implemented in response to the recent downturn. And of this, the net cost of the financial sector rescue efforts probably will represent less than 1½ percentage points of GDP (including the support provided to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac). The bulk of the projected debt increase reflects the severity of the recession that lowered output, raised spending and depressed tax revenues. The prospect that the crisis will have lowered potential growth—thereby lowering the future rate of revenue growth, as well as its current level—also could play a role. Of course, to the extent that growth surprises on the upside, the eventual burden of needed fiscal adjustment could be lightened.

In fact, there may be a brief near-term window of opportunity opening for U.S. fiscal policy adjustment that shouldn't be missed. For now, U.S. interest rates remain low by historical standards—in part due to low growth and inflation prospects, but also reflecting a low risk premium on U.S. government debt. As a result, total public debt service payments have not risen relative to GDP, despite the sharp rise in the U.S. debt-to-GDP ratio. Moreover, as the economy gains momentum, automatic stabilizers will help to lower the deficit—at least in the short run. In our view, the United States needs to make the most of this window of opportunity to tackle structural fiscal problems—especially entitlements—before real rates begin to renormalize, and the positive impact of the automatic stabilizers on the deficit recedes, adding to the perceived difficulty of making progress on longer-run fiscal challenges.

The ongoing debate on how best to achieve medium-term fiscal consolidation has received an important boost from the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform. In its recent report, the Commission proposed an ambitious consolidation plan, emphasizing the need for broad-based revenue and spending measures. The plan sets very ambitious targets—to stabilize public debt by FY2014 and return it to its pre-crisis level of about 40 percent of GDP by 2035. Under the Commission's proposals, tax expenditures would be scaled back, allowing marginal tax rates to be reduced. Social Security would be put on a sound financial footing through measures such as means-testing benefits and increasing the retirement age. And to contain health care costs, significant medium-term savings would be attained through a reform of cost-sharing rules and of certain public programs, and also by setting limits—beginning in 2020—on the growth of all federal health-related transfer programs. Another widely-cited idea to support fiscal consolidation—although not put forward by the Commission—is to introduce a national consumption tax, such as a value-added tax—or VAT. Such a measure could enhance national savings while raising revenue with limited economic distortions.

The Commission also calls for reforming budgetary processes to help keep deficit reduction on track. These would include caps on discretionary spending through 2020—with the goal of bringing such spending in real terms back to 2008 levels by 2013; and from then onwards limiting its growth to one-half the projected inflation rate. More generally, by enshrining fiscal targets (including the debt-to-GDP ratio) in budget proposals and by enacting concrete legislation relatively soon, private sector expectations could become progressively more optimistic about fiscal policy prospects, helping the sustained effort that will be needed to anchor fiscal credibility.

Fiscal consolidation not only is a challenge for the federal government, but also for state and local governments. State and local debt currently amounts to about 20 percent of GDP, or about a third of the size of the federal debt. However, unfunded state and local pension and retirement health care entitlements pose significant medium-term risks, as they are estimated at anywhere from $1 trillion to $3 trillion, or possibly equal in size to their outstanding debt. In some states and localities, servicing such a debt burden under current constitutional and other legal strictures would require significant cuts in discretionary spending and/or huge tax increases. Although many states and localities already have started facing these issues, for example by scaling back retirement benefits for new employees, much more decisive action will be required over time in order to reduce medium-term solvency risks.

In contrast to the federal government, most state and local governments are mandated to maintain balanced operational budgets. While this arrangement has prevented a greater run-up in debt, it also has mandated cuts in discretionary spending (and other measures like staff furloughs), following a period in which such spending had increased significantly. Emergency federal transfers, covering about a third of the states’ shortfalls in FY2009 and FY2010, have helped to cushion the blow some extent. For now, state and local revenue appears to be recovering, with tax receipts up 5 percent on an annual basis in the third quarter of 2010. However, the expected phase-out of federal emergency transfers, combined with the need to re-build fiscal reserves and create room for rising entitlements, mean that fiscal consolidation at the local level will remain an ongoing and urgent challenge for some time to come.

Implications for the global economy

With the United States still accounting for a quarter of the global economy, a strengthening of the U.S. recovery would have positive global implications. For example, it is estimated that the effect of fiscal stimulus boosted U.S. imports in 2010 by about $100 billion. Although this represents only about 1 percent of global imports, this added demand undoubtedly made a larger contribution through indirect effects on partner country growth. Perhaps more importantly, the stimulus played a helpful role in underpinning confidence by reducing the risk of a sharper and more sustained global downturn.

Looking forward, sound U.S. public finances will be essential for achieving the G-20 Leaders’ triple goals of strong, sustainable and balanced global growth. Moreover, the absence of a credible, medium-term fiscal strategy eventually would drive up U.S. interest rates, with knock-on effects for borrowing costs in other economies. According to IMF calculations, each percentage point increase in the U.S. debt-to-GDP ratio could drive up long-term interest rates by roughly 3 basis points. Under the baseline IMF forecast, therefore, the expected higher U.S. debt could contribute up to an additional 100 basis points to long-term bond yields by 2016, over and above the expected baseline rate increases. And the longer fiscal consolidation is delayed, the more likely would be a sharper rise in Treasury yields—which could prove disruptive for global financial markets and for the world economy.

In these circumstances, if the U.S. makes a meaningful down-payment on medium-term consolidation—for example, by making clear progress on reforming the tax system and entitlements—it would represent a “demonstration effect” that would add credence to global adjustment efforts.

United States fiscal consolidation therefore could provide a powerful example of the potential benefit of global policy cooperation. As discussed in the October 2010 World Economic Outlook, fiscal consolidation—when analyzed in isolation—tends to depress near-term growth, but boost it over the longer term. Thus, it is understandable that Governments may be reluctant to adopt fiscal adjustment measures in light of the short-term cost. However, if at the same time trading partners adopt policies that support their own domestic demand, the resulting boost to their imports will help to offset their partners' costs of fiscal consolidation, thus making the adjustment more likely to occur. In other words, collective policy action can help to deliver a solution that is better for all.

International policy cooperation

Although it is still early days, there is potential progress to report on international cooperation. In the wake of the crisis, the world’s largest economies are creating a novel mechanism to help guide fundamental economic policies in the post-crisis era, underpinned by what is intended to be a serious and specific process of mutual assessment. I am referring to the G-20’s Framework for Strong, Balanced and Sustainable Growth, launched at their Pittsburgh Summit in September 2009.

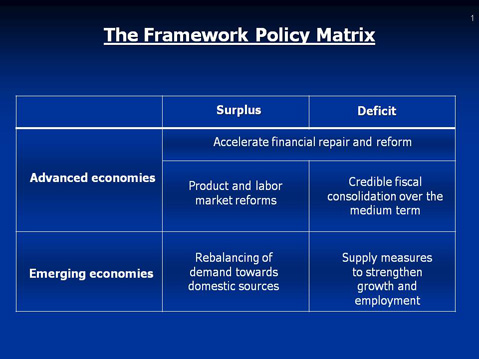

The backbone of this Framework is a multilateral process through which G-20 countries have identified objectives for the global economy and the policies needed to reach them. There is a broadly shared consensus that coherent and consistent adjustment efforts will be required by all G-20 economies if the goals are to be attained. In general terms, there is agreement regarding the nature of the required policies (Figure 1).

The G-20 members also have committed to the “Mutual Assessment Process”, or MAP, through which their progress towards meeting shared objectives will be assessed. For its part, the IMF has been asked to provide technical and analytical support, with inputs from other international organizations on issues such as labor and product markets, financial markets, and trade.

In an initial stage, G-20 members shared with each other—and with IMF staff—their policy plans and economic projections for the next 3–5 years. These were evaluated by the IMF, against the common framework goals. In the Fund’s view, the projections were relatively optimistic and subject to notable downside risks. In addition, they did not provide for sufficient fiscal adjustment, and implied limited progress towards external rebalancing.

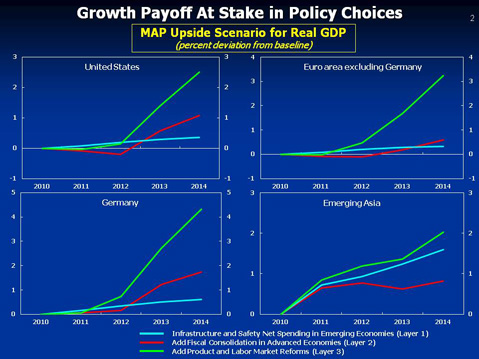

The IMF used two alternative scenarios to highlight the central aspects to judging prospective outcomes. First, a downside scenario quantified the implications of the key risks to the authorities’ projections. At the same time, an upside scenario suggested actions that could improve the outlook and bring all countries closer to their objectives. The basic insight of the upside scenario is that there is a coherent set of alternative policies that reflects a process of optimization in a global setting that—if implemented—would be expected to produce a superior outcome (relative to the baseline) for all G-20 economies. (Figure 2)

In this sense, prospects for whether the MAP upside policies will be implemented depend principally on the answers to two questions. First, do the G-20 authorities accept that the superior alternative policy set is real and realistic? If so, it is in every G-20 member's interest to implement the indicated policy adjustments. Second, does each G-20 member trust that the others will follow the policies indicated for each of them?

At their Toronto and Seoul Summits in 2010, the Leaders affirmed and reaffirmed their intention to aim for the MAP’s superior outcome. In Seoul, they endorsed new aspects that are designed to increase the likelihood that all G-20 members will implement the intended policies, including the use of agreed "indicative guidelines" to gauge progress on reducing imbalances. They also made detailed, country-specific policy commitments that could bring the global economy closer to the upside scenario. These were published as a 49-page attachment to the Seoul Leaders' Declaration.

Of course, the MAP lacks enforcement “teeth”. And its development will take time, as all countries want to be assured that the process reflects their views and interests. But so long as each authority accepts that the upside potential exists, each will have a concrete incentive to seek it.

Returning to the initial topic, early action that boosts prospects of a credible medium-term U.S. fiscal consolidation would enhance the prospects for effective international policy coordination. By demonstrating that the United States is ready to do its part in taking the steps needed to deliver strong, stable and balanced global growth, other countries will be encouraged to follow through on their commitments, as well. And my Fund colleagues and I are convinced that effective international policy cooperation can improve global economic outcomes, and that the chances of success in this effort are the most promising that we have seen.

IMF EXTERNAL RELATIONS DEPARTMENT

| Public Affairs | Media Relations | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-mail: | publicaffairs@imf.org | E-mail: | media@imf.org | |

| Fax: | 202-623-6220 | Phone: | 202-623-7100 | |