Economic Shifts and Oil Price Volatility, Remarks by John Lipsky, First Deputy Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund

March 19, 2009

First Deputy Managing Director, International Monetary Fund

At the 4th OPEC International Seminar

Vienna, March 18, 2009

As prepared for delivery

| Download the presentation (200 kb PDF) |

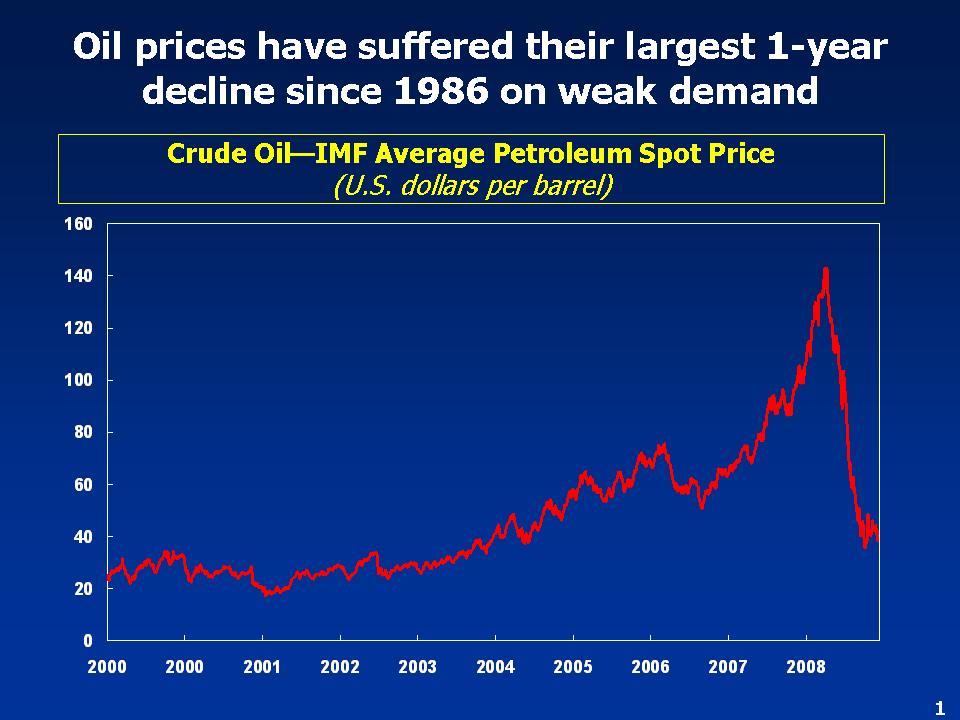

Good afternoon, Ladies and Gentlemen. I would like to thank OPEC for organizing this timely seminar. We face extraordinary conditions in the global financial system and the global economy, with important consequences for the global oil market. Indeed, when I spoke at the International Energy Forum in Rome last April, the IMF’s Average Petroleum Spot Price was at $115 a barrel. Two months later at the Jeddah Energy Forum, it had risen to $135. By year-end, it stood at $36. In recent days, it has fluctuated around $45.

Needless to say, such dramatic price variations over a short period have had large consequences for oil consumers and producers, as well as for policymakers around the world. In my remarks today, I will address the recent oil price fluctuations, focusing on the underlying causes and effects, whether these fluctuations are having a negative impact on the global economy, and whether there are practical remedies available that would reduce fluctuations in a way that would enhance global economic performance.

The Global Downturn and Oil Market Fundamentals

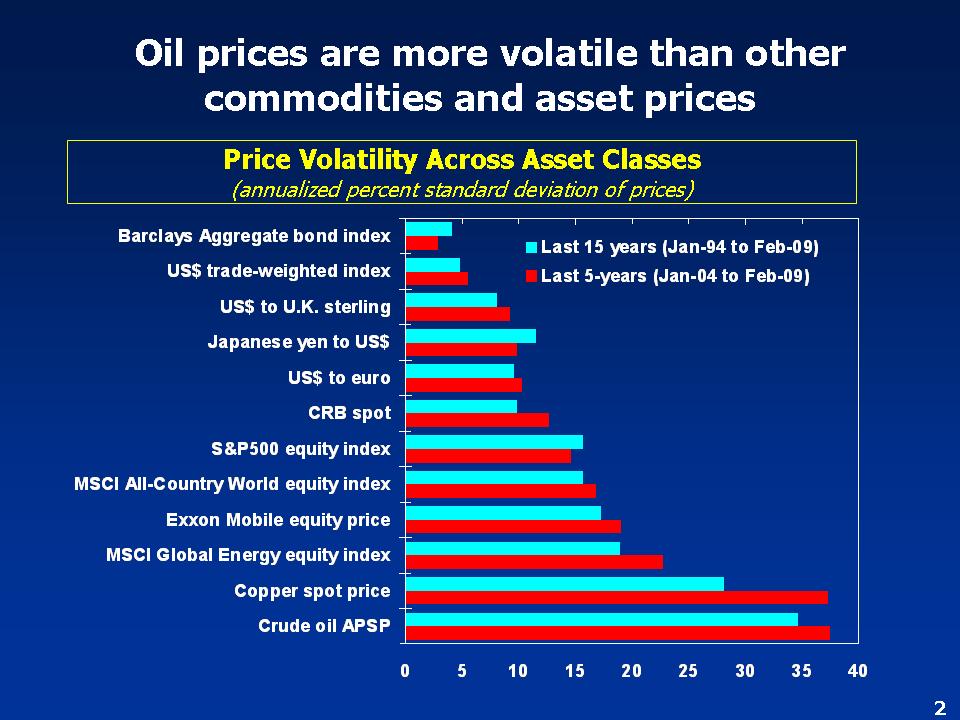

Oil prices traditionally have been more volatile than many other commodity or asset prices.

Moreover, the presence of high volatility commonly is associated with claims that markets often overshoot relative to underlying fundamentals. It would appear obvious to most observers that the price swings of the past year represent prime examples of overshooting. However, this conclusion may not be as valid as it may appear at first glance. After all, changes in underlying economic fundamentals themselves can lead to complicated price dynamics.

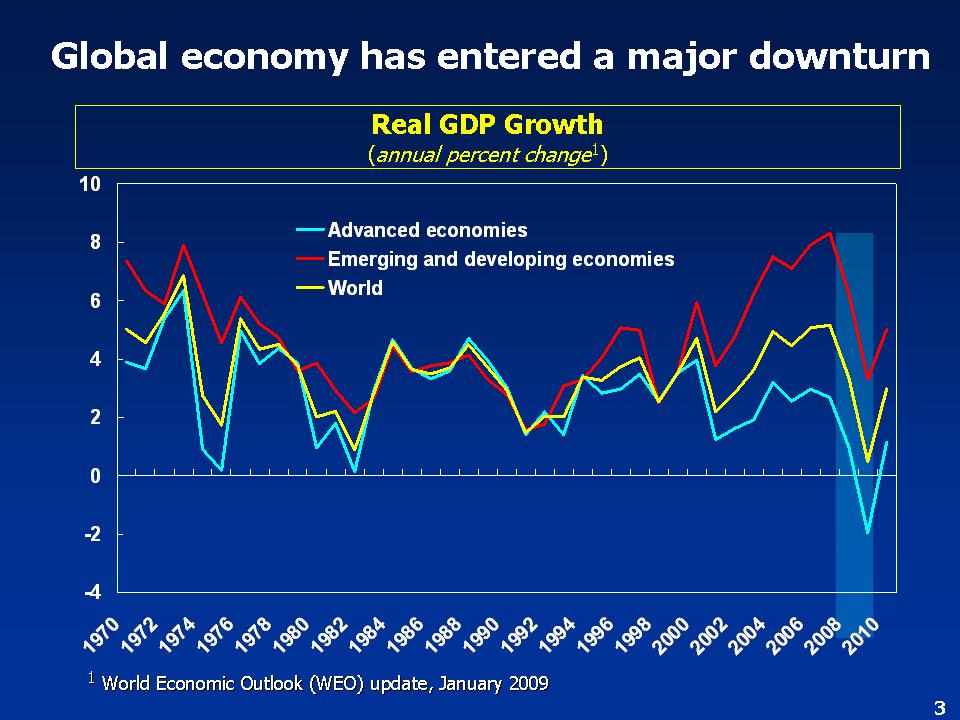

Thus, we must begin with a good understanding of the factors shaping oil demand and supply—as well as other factors affecting oil market conditions —before we can meaningfully discuss price overshooting. First among these factors is the state of the global economy. Clearly, the dramatic decline of oil prices since July 2008 is first and foremost a response to an unexpectedly rapid and sharp deterioration in near-term global economic growth prospects.

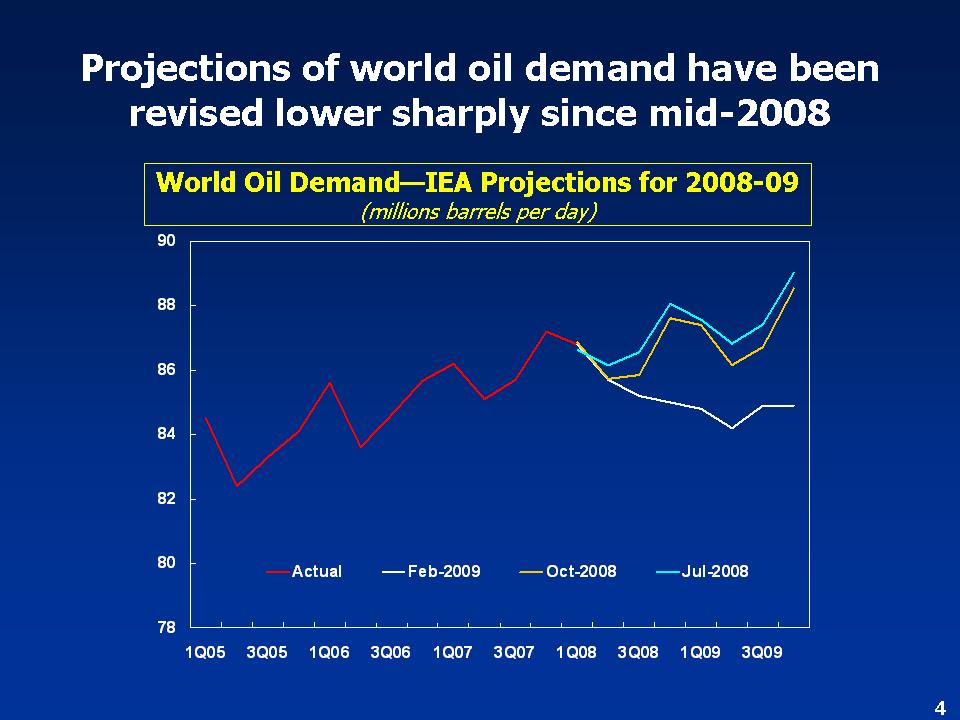

From today’s perspective, it seems likely that global output will contract in 2009 on an annual average basis. There is no modern precedent for such a severe downturn. As a result, oil markets have had to adjust quickly to the prospect of a sustained period of weakened consumption in both advanced and emerging market economies after many years of robust demand increases.

Besides immediate downward pressure from the global business cycle, the medium-term outlook also has weakened. Global growth is not expected to recover any time soon to the rapid pace achieved in 2003-07, as the financial crisis will have lasting effects on credit and capital flows. In particular, economic growth in emerging and developing economies is unlikely to return quickly to the very high rates seen during 2003-07. Oil demand today appears likely to grow at a more modest rate over the next five years or so compared to the paths projected only 9 to 12 months ago. That said, the opening up of higher cost oil reserves to satisfy rising demand remains inevitable, even though the relevant demand will emerge later and perhaps more gradually than assumed previously. Hence, we still expect prices to rise as the global economy recovers, although not at the dramatic pace recorded in 2007 and first half of 2008. Of course, this view is widely shared; oil futures price curves, for example, have been upward sloping since about mid-2008, but do not show a return to the prices registered in the first half of that year.

Have Prices Been Overshooting?

Returning to the issue of price overshooting, a key question is whether oil prices have declined more than could or should have been expected, given the changes in both the near- and the medium-term outlook. Recent movements have been striking: The price of crude oil has fallen by more than 70 percent from its 2008 peak. This represents the largest percentage drop ever experienced over such a short period, surpassing even the declines of 1986. In comparison, the CRB spot price index, a gauge of broad commodity price developments, has decreased by about 35 percent from its 2008 peak.

Of course, oil price declines in global slowdowns generally have been large. In current U.S. dollars, oil prices declined by about 30 percent on average during global slowdowns since the 1980s. Moreover, these corrections were of broadly similar magnitudes when measured in inflation-adjusted terms. Simple statistical analysis suggests that an unexpected change in annual global growth of one percentage point has been associated with an oil price decline of about 10 percent in the same year. From this angle, an oil price fall of at least 40 percent could have been expected, if the downward revisions since early 2008 in the IMF’s global growth forecast of more than 4 percentage points can be taken as representative of consensus views. Of course, evidence based on the very recent past must be interpreted cautiously, given the lack of a clear precedent in the post-World War II period to the current global financial crisis.

There are two basic reasons for large oil price responses to the global business cycle. First, output in oil-intensive sectors, including manufacturing sectors, construction, and transportation, tends to contract more than overall output in a downturn. In addition, output in emerging and developing economies has slowed rapidly, adding to the downward pressure on prices; oil demand in these economies responds strongly to income changes. Second, and even more importantly, the short-term price responsiveness of oil demand and supply generally is low. Even small shifts in demand require large shifts in spot prices in order to clear markets. Such movements typically unwind gradually as demand and supply respond to the change in prices. Simulations of the Bank of Canada-IMF Global Economic Model that were reported in the October 2008 World Economic Outlook illustrate how low short-term price responsiveness in both the supply and demand for oil can trigger large spot oil price adjustments in response to changes in global growth expectations.

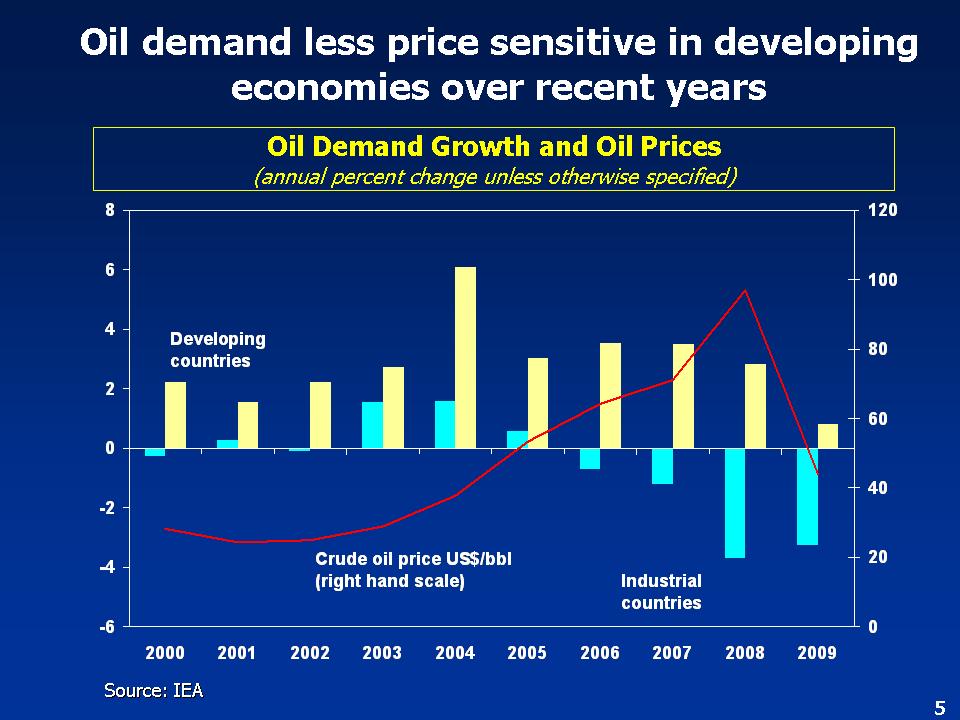

Moreover, the price responsiveness of demand appears to have decreased in recent years. In particular, the pass-through of international market prices to domestic end-user prices had been reduced through government action seeking to smooth the impact of price upswings on local prices. This has been particularly true for many emerging and developing countries. Accordingly, oil demand for these countries showed very little sensitivity to international price increases during the global boom, in contrast to demand in the advanced economies where the pass-through was more complete and immediate.

Similarly, in the downturn, lower world market prices often have not been passed on to domestic prices. The implication is that the oil price response in global markets to the unexpected deterioration in cyclical conditions should be even larger now than it has been in past downturns.

In short, strong short-term international market price responses to shifts in growth expectations do not necessarily constitute overshooting, but may simply represent the normal oil market adjustment process. That said, the magnitude of the oil price correction in the second half of 2008 was exceptionally large relative to the probable shifts in near-term growth expectations.

The speed and scope of the weakening of medium-term fundamentals in the wake of the financial crisis surely contributed to the exceptionally large correction. As a result, the capacity constraints that were driving up oil prices from 2005 until mid-2008 are unlikely to be binding again any time soon. As you all know, with the oil sector broadly producing at capacity from 2005, the high cost and the 8- to 10-year lags involved in increasing production capacity required large price increases to keep demand in check while creating the incentives to invest in higher-cost sources.

The price impact of the weaker medium-term outlook is difficult to quantify. Nevertheless, the judgment of IMF analysts is that this weakening in the medium-term growth outlook—together with the depth of the current downturn—accounts for most of the recent dramatic oil price declines. From this point of view, the possible role of overshooting in the recent price decline would appear to be relatively modest. The same is true for early 2008—overshooting on the upside relative to fundamentals likely was modest.

Commodity Financial Investment and Overshooting

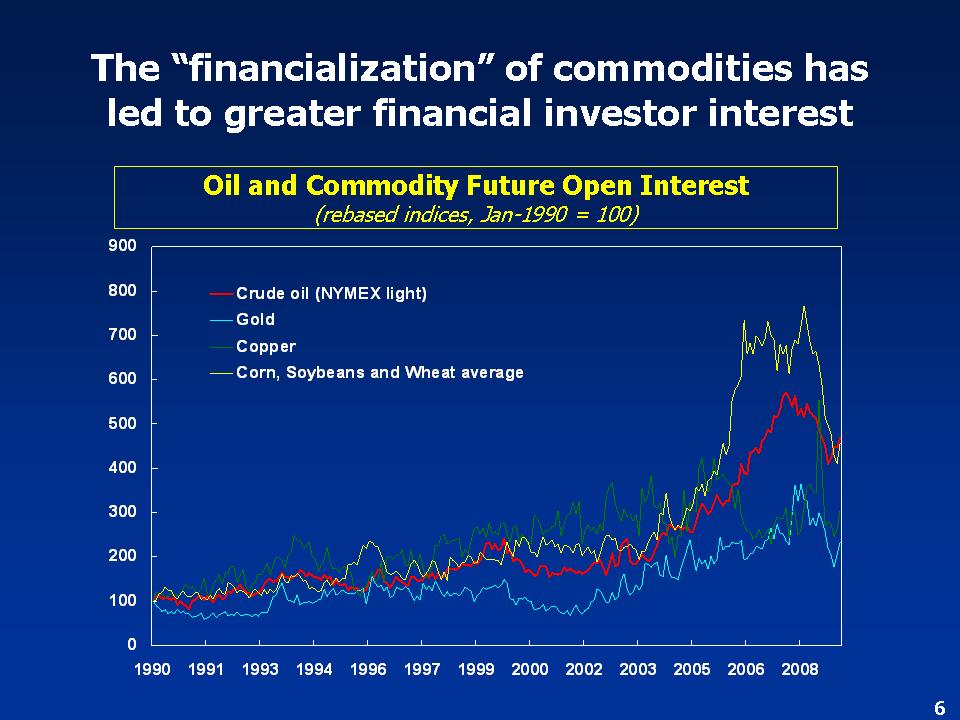

Even if it is not the critical part of the story, it is still worth asking what factors explain the price overshooting. A popular explanation has focused on the role of financial investors, as commodity derivatives have emerged as an alternative asset class.

The increasing integration of financial and commodity markets has been driven by two main factors. First, institutional investors have concluded that they can improve the risk-return balance of their portfolios by adding alternative asset classes such as commodity futures and related instruments. The correlation of the returns on these assets with those on their core holdings of equities and bonds has been relatively low, and increased commodity exposure has provided diversification benefits. Second, investors such as hedge funds increasingly sought to take leveraged positions in alternative asset classes such as commodities, given attractive risk-adjusted returns. While commodity investment appears to have partially reversed in the recent financial turmoil, the structural factors favoring such investments are likely to remain in place over the long run.

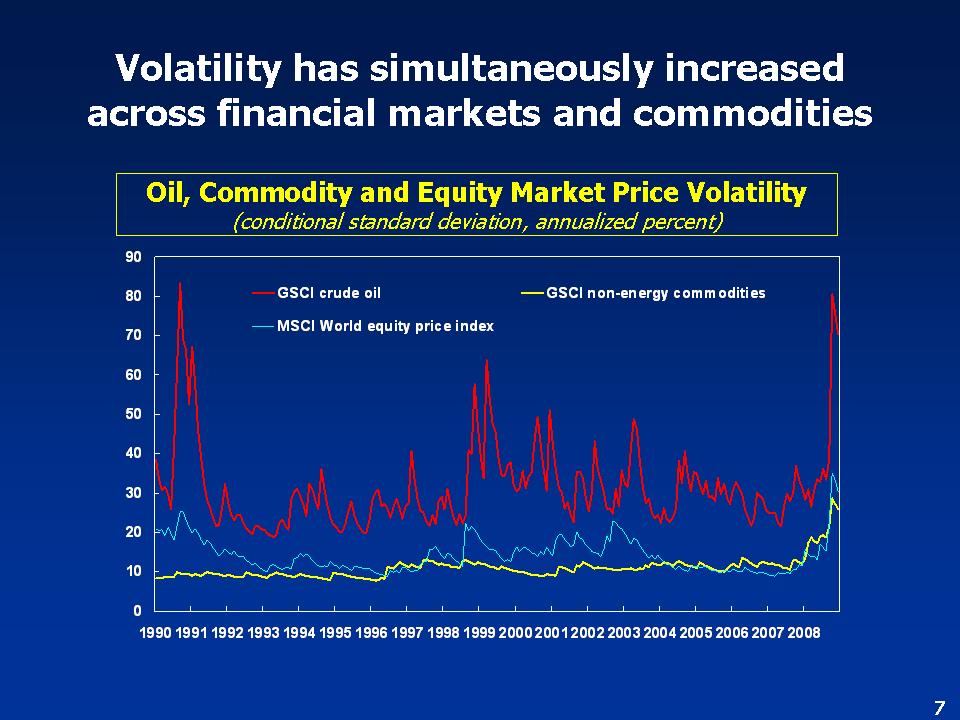

The financialization of commodity markets should be welcomed at least in principle. The presence of financial investors willing to take long forward exposure to crude oil has enhanced the potential for risk-sharing and hedging. In well-regulated and transparent financial markets, it also should improve the process of price discovery and contribute to price stability, to the benefit of both producers and consumers. Indeed, by most measures, oil price volatility has remained broadly constant during 2002-07, despite rapid financialization.

Nevertheless, short-term effects may have clouded the longer-term benefits in the past few years. In particular, the entry of new investors who follow momentum strategies—buying commodities that have experienced high returns during some recent period and selling or shorting those that have underperformed—may have influenced market behavior. A rapid increase in the number of investors following such strategies have driven prices away from fundamentals at least to same degree. Indeed, we have argued that portfolio shifts into commodity assets in late 2007 and early 2008 contributed in part to the rapid rise in oil prices at the time, as distinct from increasing volatility.

While we have to be cognizant of the short-term effects of the apparent increase in momentum trading, IMF staff analysis has not demonstrated any sustained and systematic connection between various measures of increased financialization and either price volatility or price changes. Even more tellingly, inventory holdings of oil and other major commodities remained low or even declined during the boom period from 2003 to mid-2008. If momentum trading had been the primary drivers of price trends during this period, this impulse from financial markets would have required rising speculative holdings of real assets—that is, inventories— for market clearing, given that oil consumption eventually would have declined with higher prices.

Momentum trading became a pointed concern during the financial turmoil of September-October last year. Some popular commodity investment vehicles—such as index total return swaps—carry counterparty risks. Like others, commodity investors became increasingly wary of these risks and lowered exposure by unwinding positions, thereby reducing market liquidity and increasing price volatility. Similarly, reduced access to credit forced some investors to unwind leveraged commodity investment positions. While the scarcity of data prevents a more definitive assessment, the unwinding of commodity positions may have accelerated the momentum in the price declines during this period. Nevertheless, this momentum did not last. Non-commercial oil futures positions, for example, started to rise again last November, at a time when oil prices were still falling. And inventories should have declined, rather than increased, as they did, if prices were expected to continue to fall.

Overall, therefore, our view remains that financial market dynamics and flows have not been a major driver of recent oil price trends. Moreover, other factors potentially contribute to price overshooting. In particular, difficulties related to the formation of realistic price expectations are likely to boost price volatility. Expectations matter because oil is a storable commodity, so spot prices reflect not only current, but also expected future market conditions. A first difficulty is that data limitations make the assessment of oil market conditions difficult. Comprehensive data on global demand and supply are often lagging and frequently revised, while global inventory data are not available. Price expectations are therefore formed with partial data on demand and supply as well as on recent price movements themselves, as the latter are the most readily available indicators of current market conditions. The result can be “momentum” in price expectations and, therefore, some price overshooting, on both the upside and the downside. A second difficulty is the considerable uncertainty about near- and, even more so, longer-term supply and demand prospects. The increasing volatility of futures prices in recent years is testimony to the difficulties involved in identifying a fundamental level for oil prices. Against these difficulties, markets can be influenced by sentiment in the short term. Clearly, in the current downturn, sentiment must weigh on prices.

The Effects of Large Oil Price Swings

The oil price decline has already contributed to a sharp deceleration in headline inflation across the globe. Combined with the effects of rising economic slack, average inflation in the advanced economies is expected to decline from 3½ percent in 2008 to a record low ¼ percent in 2009. In emerging and developing economies, inflation also is expected to subside to 5¾ percent in 2009 and 5 percent in 2010, down from 9½ percent in 2008. The fall in inflation has created much needed room for monetary policy easing.

Falling oil prices also are boosting household purchasing power. Although this has not been sufficient to prevent sustained weakness in consumer spending and business investment, lower oil prices will contribute, along with expansionary monetary and budget policies, to an eventual stabilization in aggregate demand and recovery in growth. Estimates based on our January World Economic Outlook forecasts suggest that the redistribution of purchasing power from oil exporters to oil importers from the decline in oil prices in 2009 could be as high as 1½ percent of global GDP. Thus, the impact on consumer spending and global growth might be close to the contribution from the fiscal stimulus now being implemented in many countries.

While oil price declines on the downside undoubtedly bring stabilization benefits to the global economy through these two channels, we should remain cognizant of the longer-term risks of low prices and heightened volatility. Taken together, these developments reduce the net present value of potential projects and curtail the oil sector’s internal free cash flows. The latter will force some producers to seek external financing, which even some investment grade borrowers find difficult to obtain right now. Moreover, the recent elevated levels of price volatility have raised uncertainty about project returns. All of these factors have contributed to the deferral of capital expenditure, particularly for those marginal investment projects that had depended upon the high crude oil prices of 2005 to mid-2008, such as Canadian oil sand extraction. The lower that prices drop now and the longer they stay low, the greater will be the negative impact on future supply. In other words, today’s low prices could be setting the stage for another price run-up in the future.

Policies to Limit Large Price Swings and Lower Price Volatility

Do we simply have to live with the large swings in oil prices and their high volatility? To some extent, the answer probably is “yes”. Nevertheless, there is scope for policies to help to reduce oil price volatility and limit the scale and frequency of large price swings, as well as for actions to cushion their economic impact.

On the demand side, policy efforts should focus on strengthening the responsiveness of domestic end-user prices to changes in market conditions, including through the pass-through of price changes in international markets. Oil demand would become more price responsive, even in the short term, reducing the tendency for large price movements. Well-targeted subsidies could protect the groups most vulnerable to large oil price changes.

On the supply side, stable and predictable investment and tax regimes will help encourage adequate investment. Acknowledging the changing structure of the oil industry, there are advantages to greater cooperation and synergies between national and international oil companies. Well-designed partnerships could take advantage of their different strengths, thereby increasing investment in the oil industry as a whole.

More timely, global, and accurate data on oil demand, supply, and inventories are critical to reducing oil price volatility, given current difficulties in assessing oil market conditions. Markets still rely on a narrow set of data, notwithstanding welcome progress under the Joint Oil Data Initiative (JODI).

Greater market transparency and much strengthened regulatory oversight will help to maximize the benefits that financialization offers, while at the same time reducing the potential risks to price stability from momentum trading. In particular, more frequent and more disaggregated data on investment flows into exchange-traded derivatives contracts would shed more light on the factors influencing the price discovery process. And as commodity financial markets are global in reach, market oversight requires greater coordination among regulators. The progress being made in this regard through the Financial Stability Forum and other relevant bodies is welcome.

Concluding Remarks

Let me conclude by reiterating that the recent extraordinary fall in oil prices is first and foremost a natural response to an abrupt, dramatic change in global economic growth prospects. For now, the main threat to further oil market instability stems from the prospect that the global economy could weaken further in the coming quarters. Aggressive policy support measures have reduced these risks, but financial strains and economic weakness have formed a corrosive feedback loop that continues to be a threat to the global outlook.

The most pressing priorities are to stabilize the global financial system and provide effective stimulus to global aggregate demand. With effective policy actions, the global downturn can be curtailed, and a recovery can start to get under way. Looking ahead, however, the durability of any global economic recovery will in part depend upon developments in oil markets. To avoid excessive swings in prices, producers, consumers, financial investors, and market regulators need to do their share to improve the transparency, functioning, oversight and, ultimately the supply-demand balance, in global oil markets.

IMF EXTERNAL RELATIONS DEPARTMENT

| Public Affairs | Media Relations | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-mail: | publicaffairs@imf.org | E-mail: | media@imf.org | |

| Fax: | 202-623-6220 | Phone: | 202-623-7100 | |