United States of America: Staff Concluding Statement of the 2018 Article IV Mission

June 14, 2018

The Macroeconomic Outlook

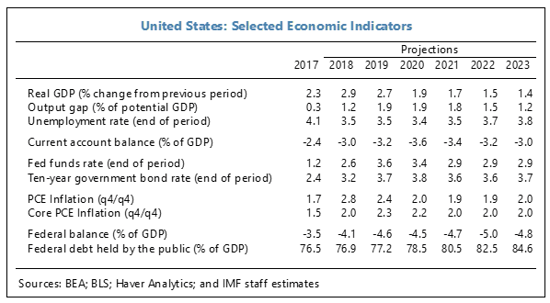

- The near-term outlook for the U.S. economy is one of strong growth and job creation. Unemployment is already near levels not seen since the late 1960s and growth is set to accelerate, aided by a near-term fiscal stimulus, a welcome recovery of private investment, and supportive financial conditions (see Table 1). These positive outturns have supported, and been reinforced by, a favorable external environment with a broad-based pick up in global activity. Next year, the U.S. economy is expected to mark the longest expansion in its recorded history. The balance of evidence suggests that the U.S. economy is beyond full employment. However, despite good near-term prospects, a number of vulnerabilities are being built-up for the medium-term (see below).

- A slow but steady rise in wage and price inflation is expected as labor and product markets tighten. After spending much of the past decade below 2 percent, core PCE inflation is expected to rise modestly above that level by mid-year. So far, wages have been growing broadly in line with (relatively weak) labor productivity growth, leaving unit labor costs virtually unchanged over the past 2 years. In the next several months, as slack is further diminished, wages and unit labor costs are anticipated to increase at a modest pace. Labor force participation is expected to be broadly stable over the near-term as cyclical forces offset the downward pull of demographics.

Fiscal Policy

- With this strong cyclical position as backdrop, the U.S. has cut taxes and raised both defense and non-defense discretionary spending. The resulting demand stimulus is expected to raise output, cumulatively, by 1½ percent by 2020, pushing the unemployment rate below 3½ percent. The tax changes are expected to have modestly positive supply-side effects, largely by incentivizing an increase in the capital stock and, in doing so, raising the level of potential GDP (by a cumulative 0.3 percent by 2020). Potential growth is expected to return to its longer-term trend (of 1¾ percent) by 2021. The effects of ongoing deregulation efforts could further raise the level of real GDP by a modest amount (although it is difficult to quantify such effects based on the available research and evidence).

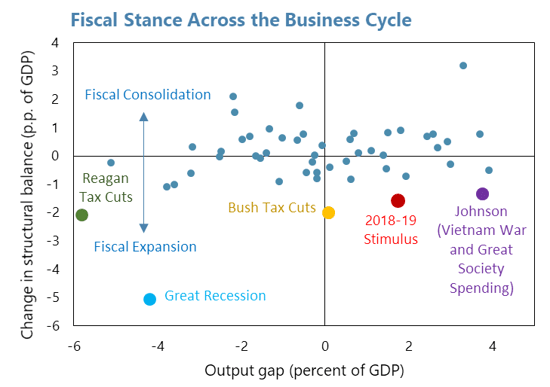

- The combined effect of the administration’s tax and spending policies will cause the federal government deficit to exceed 4.5 percent of GDP by 2019. This is nearly double what the deficit was just 3 years ago. Such a strongly procyclical fiscal policy is quite rare in the U.S. context and has not been seen since the Johnson administration in the 1960s.

- Such a procyclical fiscal policy will elevate the risks to the U.S. and global economy. This fiscal path will provide a near-term boost to the U.S. and to many of its trading partners. However, it also increases the range and size of future risks, both for the U.S. and for the global economy. These risks include:

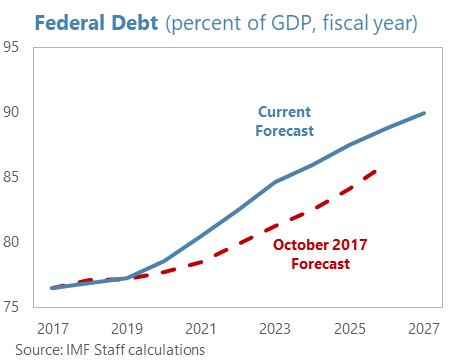

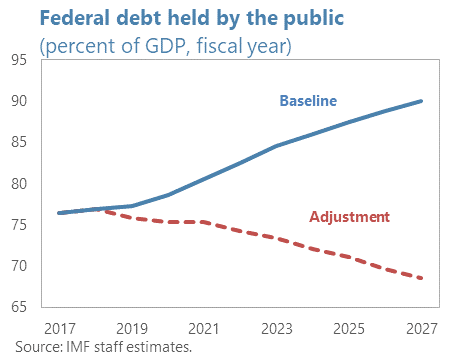

- Higher Public Debt. The increase in the federal deficit will exacerbate an already unsustainable upward dynamic in the public debt-to-GDP ratio. Even with the planned, modest fiscal consolidation that is scheduled to start in 2020, the federal debt will continue to climb, exceeding 90 percent of annual GDP by 2024.

- A Greater Risk of an Inflation Surprise. As discussed above, the tax reform is expected to have only modest effects on potential output. As such, the planned expansionary fiscal policy raises the risk of a faster-than-expected rise in inflation as capacity constraints become more binding and the economy pushes further through full employment. Such a rapid rise in inflationary pressures would force the Federal Reserve to move at a faster pace than is currently priced in by markets, potentially creating volatility and disruptions in U.S. asset markets, tightening financial conditions, decompressing term and other risk premia, and straining leveraged corporates and households.

- International Spillover Risks. The shift in the U.S. policy mix also creates important adverse risks for non-U.S. corporates, households, and sovereigns (especially those that have borrowed heavily in U.S. dollars and/or have significant rollover needs). It could also precipitate a marked reversal of capital flows, particularly to emerging markets, potentially adding to upward pressure on the U.S. dollar and worsening global imbalances. We are already starting to see symptoms of these spillover effects in other countries.

- The Risk of Future Recession. Current policies build in a gradual fiscal consolidation starting in 2020, at a time when the monetary tightening cycle is expected to be at its peak. Staff forecasts assume a gradual slowdown during this period with growth leveling off at around 1½ percent, modestly below the economy’s potential growth rate. However, such a gentle convergence of output to potential from above would be historically unusual and this forecast could prove overly optimistic. The output gap could close more abruptly, through a policy-induced recession, with negative spillovers for the global economy.

- Increased Global Imbalances. The U.S. external position in 2017 was moderately weaker than implied by medium-term fundamentals and desirable policies and the U.S. dollar is judged to be moderately overvalued. With the economy already at full employment, the fiscal boost to demand in the U.S. is likely to translate into higher import growth, an increase in the current account deficit (to around 3½ percent of GDP by 2019-20), upward pressure on the dollar, and a worsening of the international investment position. The higher U.S. current account deficit is expected to be matched by growing current account surpluses in other systemic economies. Global imbalances are expected to rise, with the various attendant risks that such imbalances convey (including possibly catalyzing public support for increased protectionism).

- There is broad agreement that increasing federal spending on infrastructure is urgently needed. However, the planned expansion in the federal deficit will leave few budget resources available to invest in a range of urgently needed supply-side reforms—including infrastructure spending—that would help boost medium-term growth and raise living standards. Indeed, the recently approved budget bill for 2018-19 provides little incremental funding for infrastructure (despite the US$200 billion in appropriations requested by the administration). Even with the administration’s efforts (to streamline the regulatory structure, assess the viability of user fees, and expand the use of public-private partnerships and tax-preferred private activity bonds), improving U.S. infrastructure will need to be backed by a sustained increase in federal spending. This increase should be structured around competitive programs geared toward high priority projects rather than formula-based, automatic allocations. However, any increase in federal outlays on infrastructure should be designed within an overall spending envelope that allows for a steady reduction in the federal deficit and debt over the next several years.

- Measures should be taken to raise the primary fiscal surplus of the general government to around 1¼ percent of GDP (1½ percent of GDP for the federal government) to put the debt-to-GDP ratio on a downward path. Specifically, such policies should include:

- Reforming social security including by raising the income ceiling for contributions, indexing benefits to chained inflation, raising the retirement age, and instituting greater progressivity in the benefit structure.

- Containing healthcare cost inflation through technological solutions that increase efficiency, greater cost sharing with beneficiaries, and changing mechanisms for remunerating healthcare providers.

- Increasing the federal revenue-GDP ratio by putting in place a broad-based carbon tax, a federal consumption tax, and a higher federal gas tax.

Such a set of policies would both allow the public debt-to-GDP ratio to fall and create the fiscal space for policies to support low- and middle-income families, promote investments in human and physical capital, and increase medium-term growth.

Monetary Policy

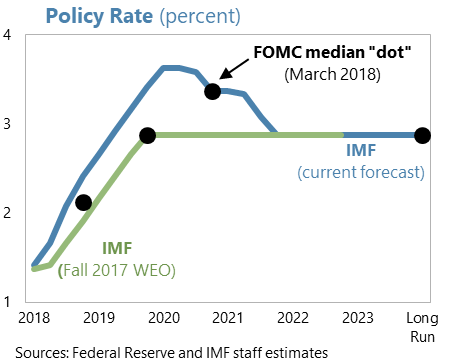

- In light of the planned fiscal stimulus, the Federal Reserve will need to raise policy rates at a faster pace to achieve its dual mandate. The Federal Reserve should be ready to accept some modest, temporary overshooting of its medium-term inflation goal (as is indicated in the range of FOMC participants’ forecasts). Even then, though, policy rates will likely need to rise for a time above the long-run neutral rate. FOMC participants’ median forecast suggests that both core inflation and the federal funds rate will rise at a moderately slower pace than in staff’s forecasts (see chart); this is consistent with their expectation of growth that is somewhat slower than staff’s forecasts in 2018-19. Barring a significant negative shock, the normalization of the balance sheet should proceed as outlined in the Fed’s policy normalization principles. In executing its monetary policy decisions, the Fed’s continued adherence to the principles of data dependence and clear communication will be vital. In this regard, scheduling a press conference after every FOMC meeting and publishing a quarterly monetary policy report (that details a central economic scenario, and description of risks around that baseline, that is endorsed by the FOMC) could help.

- For most economies, the near-term, net effect of higher U.S. growth and the expected increase in U.S. interest rates is expected to be beneficial. The largest positive spillovers are likely to accrue to Canada and Mexico, given their close economic ties with the U.S. However, even under this baseline, there could still be stress, particularly for leveraged firms and households (both in the U.S. and abroad) and/or for indebted sovereigns. Indeed, some of these strains are becoming evident in a handful of countries. Presumably, if some of the downside risks outlined above materialize, the outward effects would be far more damaging for a broader set of countries.

Tax Policy

- There is broad agreement on the objectives underpinning the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA). Specifically, as pointed out by the administration, the U.S. tax code has long needed an overhaul in order to: simplify the system; make the U.S. business tax competitive; provide tax relief to lower- and middle-income Americans; lower statutory rates and broaden tax bases; increase equity (including by taxing households at similar levels of income in a uniform way, independent of their type of business or source of income); not provide income tax cuts for the wealthy; and to achieve all of these objectives without adding to the fiscal deficit.

- In this regard, the Act contains many positive steps. These include efforts to reduce the scope of personal income tax deductions, lower marginal tax rates, create incentives for private investment, tackle base erosion and cross-border profit shifting, and reduce debt bias.

- However, the approved tax policy changes have a high budgetary cost. In addition, the temporary nature of many provisions creates significant tax policy uncertainty and instability in the tax system. As discussed above, the authorities should seek to prevent the tax policy changes from adding to the fiscal deficit by increasing the revenue-to-GDP ratio (largely through a greater reliance on indirect taxes).

- There remains scope to strengthen various provisions of the code to better achieve the objectives outlined above:

- The Business Tax. The reduction in the statutory business tax rate, to around the OECD average, and the expensing of certain types of capital spending are positive changes that, taken in isolation, will help incentivize investment and lessen the motivations behind base erosion and profit shifting behaviors. The Act, though, continues to allow for the deductibility of interest with a cap as a share of earnings. Such deductibility for debt-financed investment spending that can be expensed conveys an overly generous benefit and continues to incentivize debt financing. In addition, the cap introduces a procyclical distortion into the system (the cap becomes more binding when earnings weaken which, in a downside scenario, could exacerbate strains and bankruptcies in the corporate sector). Further, the temporary nature of the expensing provision distorts the timing of firms’ investment decisions (to favor investing before the provisions expire). In order to further increase the competitiveness of the U.S. business tax and to further lessen the distortion it creates for investment decisions, it would be preferable to go further in the direction of the TCJA and move the U.S. to a cashflow tax, permanently allowing for the expensing of all capital outlays and fully eliminating the deduction for interest spending on newly-contracted debt. Finally, the decision to levy a very low, one-time tax rate on the stock of unrepatriated profits conveys significant benefits to taxpayers that chose not to repatriate profits, at a time when the federal budget is in urgent need of revenues.

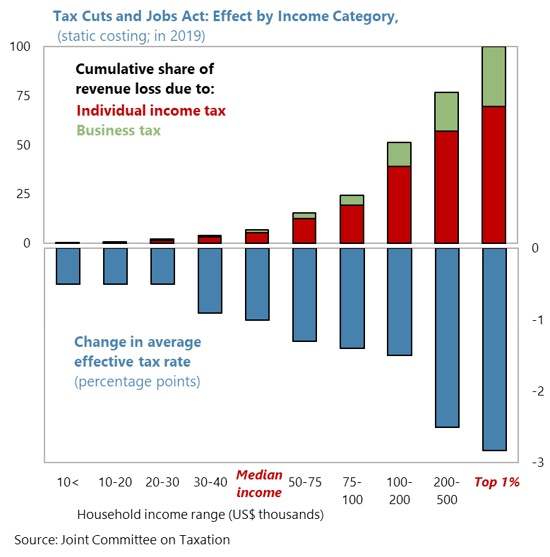

- The Personal Income Tax. The changes to the personal income tax have many positive aspects: they eliminate most itemized deductions, raise the standard deduction and eliminate personal exemptions, limit the deduction for state and local taxes, and reduce the cap on the mortgage interest deduction. Nevertheless, the net effect of the tax policy changes—which also include reductions in the burden of the alternative minimum tax and a reduction in the marginal rate for higher income households—provides greater benefits to those in the upper deciles of the income distribution (see chart). As a result, these changes are likely to exacerbate income polarization and will do little to address the pressing needs of the working poor (both of which are important, macroeconomically relevant issues that have been raised in past Article IV consultations). To better target tax relief to lower- and middle-income Americans and prevent reductions in the income tax for the wealthy, it would be preferable to recalibrate the rate structure in order to concentrate tax relief to those earning close to or below the median income (with tax relief phasing out for those earning above 150 percent of the median income). As part of this change, and in line with past advice, the coverage and generosity of the Earned Income Tax Credit could be increased and there is space to eliminate loopholes and special regimes for high income earners, including the carried interest provision. The combination of these proposed changes would support low- and middle-income households, strengthen private sector demand, incentivize work, and raise living standards.

- Pass-Throughs. Allowing for a 20 percent deduction for pass-through income creates an important mechanism for high income individuals to reduce their tax obligations by recharacterizing personal income as pass-through income. This is counter to the authorities’ objectives of increasing equity—especially between those taxpayers that can, and cannot, arrange their activities to take advantage of the deduction—and simplifying the system. The TCJA does contain guardrails that limit the use of the pass-through deduction. However, it is unclear how effective those provisions will be in preventing an erosion of the personal income tax base from high income individuals or from stopping pass-throughs from redesigning their operations to maximize their ability to qualify for the 20 percent deduction.

- The TCJA has the potential to significantly reshape the international tax system. The U.S. has abandoned its system of global taxation with deferral and moved to a modified territorial system that embeds anti-avoidance measures and a minimum tax on the offshore profits of U.S. multinationals. However, there is scope to strengthen the design of various of the international provisions in the Act:

- To better curtail global tax competition, the minimum tax (the Global Intangible Low Taxed Income or “GILTI”) provision should be imposed on a country-by-country basis so that it falls on all profits earned in low tax jurisdictions (rather than on the average global profits of multinationals that are in excess of a deemed 10 percent return on tangible assets). As it stands, the link of this provision to worldwide profits and tangible capital will create complex and distortionary effects on firm’s global investment decisions and may dilute its effectiveness in dis‑incentivizing cross-border tax competition.

- The lower tax rate for exporters (the Foreign Derived Intangible Income or “FDII”) should be eliminated to avoid the economic distortion that arises from providing a more favorable tax treatment for exports than for domestic sales. This would provide more of a level playing field for global investment decisions.

- The Base Erosion Anti-Abuse Tax (or “BEAT”) will likely serve its intended function of helping to curtail various base erosion and profit shifting behaviors, but it is also likely to be punitive for a range of legitimate commercial activities that are not linked to tax avoidance. The provision also creates a broad-ranging preference for domestic over foreign production and creates new incentives for companies to rearrange their operations to avoid application of the BEAT. These shortcomings would be mitigated, and international tax planning strategies would be better contained, by only applying this provision to those transactions that are designed to transfer profits to related parties located in low tax jurisdictions.

- As it stands, the far-reaching and innovative features of the TCJA create a complex array of both positive and negative spillovers for other countries, which stakeholders are still analyzing. The move to territoriality heightens the likelihood of profits and investments being shifted from the U.S. into lower tax jurisdictions (there is evidence that a similar move in the U.K. indeed increased outward investment to lower tax jurisdictions). However, the marked reduction in the statutory rate and preferential treatment for some exporters in the U.S. are important countervailing forces, and could encourage other jurisdictions to lower their tax rates, particularly when they are clearly above the new U.S. statutory rate. One potential effect of the innovative GILTI and FDII provisions is to encourage location of tangible investments abroad, a tendency that will be strengthened for those projects that generate sizable commercial payments with related parties in other jurisdictions (since these may become subject to the BEAT if such intercorporate transactions are paid from a U.S. entity). At the same time, the GILTI provision is likely to discourage offshore jurisdictions from competing for U.S. investments by reducing their tax rate below 13.125 percent. It may even provide a floor on competition in the statutory rate, to the benefit of other relatively high tax rate jurisdictions. Furthermore, the reform could encourage other jurisdictions to consider ways other than rate reduction to compete for tangible investment. These could include faster depreciation rates (or even expensing), consideration of their own version of the BEAT, or other measures designed to achieve a similar, broad anti-profit shifting goal. The final impact on other countries (some of which have expressed WTO- and treaty-related concerns) is likely to vary considerably according to their circumstances.

Trade Policy

- The U.S. maintains a very open trade regime. Over the years, this has supported U.S. growth and job creation and helped raise living standards. U.S. leadership on trade has encouraged a range of countries to open their own trade regime, removing tariff and nontariff barriers. There is also broad agreement that the global economy needs to be able to rely on an open, fair, and rules-based international trade system.

- However, public concern over the side-effects of open trade has increased. It is in this context that various steps have been taken, or have been proposed, by the administration to impose new tariffs or otherwise restrict imports into the U.S. These measures, though, are likely to move the globe further away from an open, fair and rules-based trade system, with adverse effects for both the U.S. economy and for trading partners. Specifically, they risk:

- Catalyzing a cycle of retaliatory responses from others, creating important uncertainties that are likely to discourage investment at home and abroad.

- Expanding the circumstances where countries choose to cite national security motivations to justify broad-based import restrictions. As such, this has the potential to undermine the rules-based global trading system.

- Interrupting global and regional supply chains in ways that are likely to be damaging to a range of countries, and to U.S. multinational companies, that are reliant on these supply chains.

- Impacting a range of countries, particularly some of the more vulnerable emerging and developing economies, through increased financial market or commodity price volatility associated with these trade actions.

- The U.S. and its trading partners should work constructively together to reduce trade barriers and to resolve trade and investment disagreements without resorting to tariff and non-tariff barriers. In such discussions, specific levels of the bilateral trade balance between the U.S. and other countries should not be viewed as either an anchor or a target (given that they are determined by a range of macroeconomic and structural forces and that targeting them is unlikely to reduce a country’s overall trade deficit). Rather, the goal should be to pursue the important gains that are to be had, for all parties, from strengthening the rules-based, multilateral trading system and from securing more ambitious bilateral and plurilateral agreements on trade and investment. The size, diversity, and dynamism of the U.S. economy leaves it especially well poised to benefit from such trade and investment liberalization. However, it is possible there will be important effects on both labor markets and the income distribution from greater trade integration. The consequences for trade-affected U.S. workers should not be ignored and policy efforts should focus on mitigating the downsides through training, temporary income support, and job search assistance (including through a broader deployment of the existing trade adjustment assistance program).

Financial System Oversight

- Important gains have been made in strengthening the financial oversight structure since the global financial crisis. Some useful steps are underway, to recalibrate and simplify financial regulations and to better tailor them to underlying risks:

- Legislation has been enacted to raise the total asset threshold to US$250 billion for bank holding companies (BHC) to be classified as systemic. This strikes a reasonable balance between a mandatary application of enhanced prudential standards and providing the Federal Reserve with the ability to deem BHCs with assets between US$100–250 billion as systemic and subject to such standards. This change will help lessen compliance costs for medium-sized BHCs but will necessarily increase the burden on high-quality and independent supervision to manage financial stability risks. Consideration could be given to continuing to apply stress-tests at a regular frequency for those banks that have assets between US$100-250 billion. In any case, implementation of these changes should be done in a way that does not weaken the ability of supervisors to take early remediation and risk mitigation actions for BHCs with assets below US$250 billion.

- Modest changes have been made to exclude custodial assets from the calculation of the Supplementary Leverage Ratio, include highly liquid municipal bonds in the definition of High Quality Liquid Assets (subject to limits and haircuts), and exempt BHCs with total assets under US$10 billion from the Volcker rule. These appear to represent appropriate tailoring of the Dodd-Frank Act framework for financial oversight.

- The Federal Reserve and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency have proposed modifying the enhanced supplementary leverage ratio (eSLR) for globally systemic important banking organizations (GSIBs) to set the ratio at 3 percent plus a buffer of 50 percent of the entity’s risk-based capital surcharge. This would make the risk-based capital requirement, rather than the leverage ratio, binding for most GSIBs. The proposal is still somewhat more stringent than international minimum standards but would reduce the buffers that have helped increase U.S. banking system resilience.

- The Treasury has argued for changes to the resolution framework to strengthen the courts’ ability to deal with complex financial failures under a new special, streamlined bankruptcy procedure. This new process would complement—but not replace—the existing Orderly Liquidation Authority and more tightly circumscribe the authority granted to the FDIC—including in the use of public money—when it resolves a financial institution. It will be important that this change is implemented in a way that does not limit the flexibility of the resolution regime, hinder rapid action, or complicate cross-border resolution.

- Finally, the Treasury has proposed steps to increase the transparency and analytical rigor of the FSOC’s designation process. These include comprehensive cost-benefit analysis and the provision of clear guidance for financial institutions that are designated as systemic. In assessing systemic risks, evaluations would be based on an activity-based framework and designation would be used only as a last resort (when systemic risks cannot be sufficiently mitigated through other means). These changes have the potential to strengthen the designation process but much will depend on how they are executed; clarifying the changes to the process and the implementation of those changes should be done at an early stage.

- When taken in isolation, the steps proposed to better tailor financial regulations are likely to have only a modest impact on financial stability risks. However, more analysis is needed to build a clear picture of the combined effect of all these changes taken together. There are potentially important interactions between the various regulatory changes, that largely move in a procyclical direction, and the effects of the procyclical fiscal policy that is currently in place. This is of even greater concern since medium-term financial vulnerabilities have been steadily building and medium-term financial stability risks are elevated.

- Future changes to financial oversight should continue to ensure that the current risk-based approach to regulation, supervision and resolution is preserved. Risk-based capital and liquidity standards should remain a central tool in incentivizing financial institutions to manage well the risks they undertake. In support of these capital and liquidity requirements, the Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review exercise should be maintained and strengthened, including its assessment of liquidity and contagion risks. The FSOC should continue its efforts to respond to emerging threats to financial stability and, in this work, there is scope to strengthen, and more fully resource, the Office of Financial Research. Finally, the U.S. should remain engaged in developing the international financial regulatory architecture and should be fully committed to agreed international standards.

- There remains a need to strengthen the oversight of nonbanks. As has been highlighted in previous consultations, there are potential weaknesses in oversight arising from the absence of harmonized national standards or consolidated supervision for insurance companies. Also, recent proposals to limit the engagement of federal authorities in international supervisory fora could prove cumbersome for the insurance standard setting process and the development of the global capital standard. Progress has been made in money market reform but there remain residual vulnerabilities in repo markets and for money market funds. There is also a need to introduce a comprehensive liquidity risk management framework for asset managers (that includes liquidity risk stress tests). Little progress has been made in reforming the housing finance system and the government sponsored enterprises. Finally, impediments to data sharing among regulatory agencies remain and there are data blind spots, particularly related to the activities of nonbanks, that preclude a full understanding of the nature of financial system risks, interlinkages and interconnections.

Competition Policy

- The market power of corporations is becoming more pronounced across a range of industries, with important macroeconomic effects. Margins between prices and variable costs—markups—have been rising steadily since the 1980s, and at an accelerated pace since 2010. Measures of industry concentration and profitability mirror this increase in market power. Corporate level data suggest that these trends have been driven by an increase in rents that are accruing to a relatively small, but growing, number of “superstar” firms (some of which have been created by a series of mergers and acquisitions). While there is significant heterogeneity in the causes underlying this rising market power, the evidence suggests that these developments are having important effects on macroeconomic outcomes including potentially depressing future investment and R&D spending, as well as weighing on the labor share of income.

- The right policy responses to this increase in market power are complex. In cases where barriers to entry or increasing returns are driving the increase in market power, and where that power is being used to price discriminate, restrict supply or engage in predatory pricing, there is a clear role for applying antitrust policies. In other cases, network and information externalities or increasing returns to scale may justify an oligopolistic structure. However, supernormal profits or rents from such market power should be taxed fairly. Care is needed, though, in not unintentionally placing an unfair tax burden on returns that arise from up-front investments (in areas such as R&D, for example). This could be achieved, for example, by moving to a cashflow tax. In any case, public policy should certainly focus on ensuring that markets remain contestable. It may also sometimes be appropriate for the entity providing the service to be regulated. Finally, insofar as increased market power arises from greater efficiency or technological innovation, there may be a public policy role to help workers displaced by such changes in market structure, including with relocation or retraining support. Such support should be broad-based and apply to all workers that are facing a transition (whether it is a symptom of changes in trade patterns, of technology, or of shifts in market power).

IMF Communications Department

MEDIA RELATIONS

PRESS OFFICER: Raphael Anspach

Phone: +1 202 623-7100Email: MEDIA@IMF.org