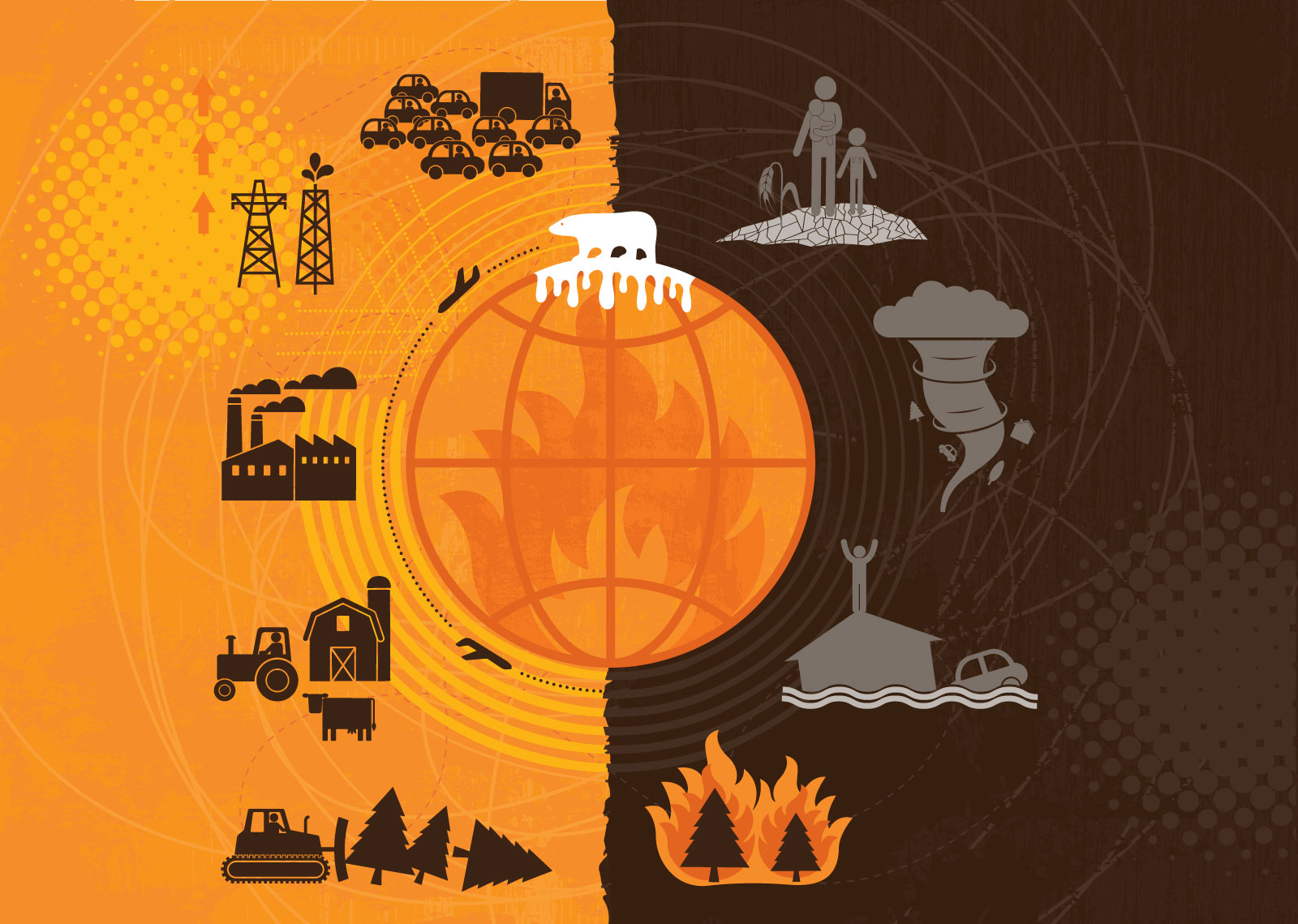

How can we address inequality in the twenty-first century? Start with climate change.

Do you prefer to hear good news or bad news first? I will begin by giving you the (unsurprisingly) bad news. Today’s world is an unequal place. Standards of living vary massively both between and within countries. To narrow it down to its most blunt statistic, if you were born in Hong Kong your life expectancy is nearly double that of someone born in Swaziland, 84 and 49 years, respectively.

The good news is that in recent decades many global indicators of living standards have improved. The Millennium Development Goals, a group of targets aimed at reducing poverty and raising living standards, were largely successful. Those living in extreme poverty dropped from 1.9 billion in 1990 to 836 million in 2015, the proportion of undernourished people in low-income countries fell from 23 percent in 1990 to 13 percent in 2014, and worldwide primary school enrollment has reached 90 percent. These statistics offer hope for a trajectory toward an equal world. There is more bad news, however, in that climate change threatens to undo this progress and create further inequity.

The definitive challenge of our time

Climate change will be the definitive challenge of the 21st century, yet it is largely pushed aside in discussions of policies to address inequality. If warming is not limited to 1.5 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels the results could nullify most, if not all, the progress made in reducing inequality. Climate change will further magnify existing inequality as low- and middle-income countries will bear the brunt of its impact. As rainfall patterns become more unpredictable, sea levels rise, and storms become more intense, the expected impacts on low-income countries are severe.

An integral problem of advocating for action is that people perceive climate change as a distant threat, but its ramifications are already being witnessed in many parts of the world. Cities such as Dakar in Senegal are flooded annually. The semiarid Sahel region is encroaching on once fertile farmland. California was subjected to the deadliest wildfires in its history last year, with record amounts of land burnt to ash.

Climate change is an exemplary illustration of inequality in the 21st century. The United States is responsible for 26 percent of global cumulative greenhouse gases, and Europe is responsible for an additional 22 percent. In contrast, the entire continent of Africa contributes just 3.8 percent. While high-income countries are responsible for the vast majority of greenhouse gas emissions, it is the low-income countries that will face the repercussions. Many low-income countries are located in the tropics, which are far more vulnerable to rising temperatures than high-income temperate countries such as the United Kingdom. Entire agricultural systems will be lost, famines will hit numerous areas, and diseases such as malaria are predicted to become more widespread. Already we are seeing pastoral farmers in Chad struggling to survive due to a lengthening dry season. The largest lake in the country, Lake Chad, has shrunk 90 percent in the past 50 years.

Nevertheless, this division is not solely between high- and low-income countries, it will also prevail within countries. Last year Harvard researchers coined the term “climate gentrification”: properties at higher elevations in inland Miami were becoming more expensive due to flooding risks associated with climate change. Again, it will be those who cannot afford to buy their way to safety who are left in at-risk areas.

Along with creating new problems for low-income countries, climate change will exacerbate existing inequalities. Low-income countries do not have the fiscal capacity to deal with severe disruptions to infrastructure. Increased flooding will lead to the spread of waterborne diseases such as cholera and dysentery due to damaged water provisioning services. Cases of malnutrition are expected to rise dramatically as droughts in tropical areas result in lower crop yields. In countries such as Madagascar, where over 70 percent of the population are rural farmers, this will be devastating. Due to the complex and far-reaching nature of climate change, the knock-on effects for low-income countries are multitudinous. It will make receiving a quality education more difficult, intensify existing gender inequalities, provoke conflict, destabilize governments, and force people to leave their homelands. These countries do not have the funds or support to deal with the scale of the problems climate change will bring.

“Climate migrant” is a term we will hear frequently; the World Bank predicts there may be up to 140 million such migrants by 2050. In Europe, the media often refer to refugees seeking security as a “crisis,” yet 84 percent of refugees are currently within low-income countries, and people in poorer countries are roughly five times more likely to be displaced by weather events. This is yet another burden low-income countries are left to deal with. Even high-income countries threatened by climate change are far more able to deal with its consequences. Shanghai, one of the cities most vulnerable to flooding, has been building flood-defense infrastructure since 2012; one such project is expected to cost £5 billion. Low-income countries do not have such capital to invest.

Stepping up to the plate

This brings us to the main question: what can be done to tackle the problem? Many things, actually. The two main aspects of dealing with climate change are mitigation and adaptation. As high-income countries produce the majority of greenhouse gas emissions, the onus is on us to minimize them.

It seems that climate scientists are finally winning the battle of awareness, as a recent poll found that 73 percent of Americans now believe that climate change is occurring, a record high. Furthermore, 72 percent said it was personally important to them. This is significant because it puts the onus on governments and companies to act in citizens’ interests. Mobilizing the public to put pressure on these groups will be the true turning point, and there are already signs of this happening. Over 70,000 people marched in Brussels in January demanding better climate action from the government, and citizen groups all over the world—including in Ireland, where I am writing this—are taking their governments to court over lack of action on climate change.

The key point is that minimizing emissions sooner rather than later is an imperative as it is ultimately the cheaper and easier option. While there has been a focus on individual actions in reducing emissions, such as choosing low-emission transportation and buying seasonal produce, it is about time that governments and the private sector stepped up to the plate.

The 2017 Carbon Majors Report found that just 100 companies have produced over 70 percent of global industrial greenhouse gas emissions since 1988. This statistic gives us an opening to create proper, systemic change through demanding better practice from these corporations. The private sector has a great ability to bring about lasting change not only by mitigating climate change but also by bringing people out of poverty through employment. As many countries turn toward nationalism, the private sector is one of only a few candidates in the search for a climate leader. That said, climate change will not be mitigated without governmental cooperation through environmental policies such as carbon taxes, national adaptation plans, and participation in multilateral treaties. Economic activity in the 20th century was largely based on fossil fuels, and carbon taxation will speed up development and adoption of alternative fuel sources. Climate change is a transboundary issue and requires global collaboration to both mitigate its effects and assist lower-income countries with adaptation.

Mitigation and adaptation are not a silver bullet for tackling existing inequalities across the world. This will be achieved through policymaking and reform of tax systems in conjunction with tackling climate change. However, I chose to write about climate change as I found it was largely sidelined in discussions surrounding inequality. Until climate change is mitigated and vulnerable countries are helped to adapt to its impacts, no true progress can be made in the quest to tackle inequality.

If inequality is truly an issue that high-income countries care about, as they claim to, then they will not let climate change continue on its current pathway to devastating low-income populations. At present we are certainly not on track to limit atmospheric warming to 1.5 degrees by the end of this century. We are not even on track to limit it to 3 degrees. According to current estimates we will reach 4 degrees warming by 2100, a year that babies born today in places like Hong Kong (but not Swaziland) will live to see. With young activists like Greta Thunberg, the 16-year-old who gave an impassioned climate advocacy speech at Davos, I have hope that future leaders will act on this issue, but we cannot afford to wait for them. We need climate leaders now.

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect IMF policy.