The Cost of Conflict

Finance & Development, December 2017, Vol. 54, No. 4

Phil de Imus, Gaëlle Pierre, and Björn Rother

Middle East strife is exacting a heavy toll on regional economies

Nowhere in the world has conflict been as frequent or as violent over the past 50 years as in the Middle East and North Africa. On average, countries in this region have experienced some form of warfare every three years. Today, rarely a day passes without media reports of violence, large-scale human suffering, and major destruction in such countries as Iraq, Syria, and Yemen.

These conflicts have enormous human and economic costs, both for countries directly involved and for their neighbors. Libya, Syria, and Yemen experienced deep declines in their economies with sharp increases in inflation between 2010 and 2016. Iraq’s economy remains fragile owing to the conflict with the Islamic State (ISIS) and the fall in oil prices since 2014. Clashes have also spilled over to other countries, causing problems that are expected to persist—such as economic pressures from hosting refugees. Violent conflict has worsened conditions for a region already facing structural deficiencies, low investment, and, more recently, the oil price drop, which has had a substantial impact on oil-producing economies.

Key channels

There are four major channels through which conflict affects economies.

First, death, injury, and displacement seriously erode human capital. While the figures are difficult to verify, half a million civilians and combatants are estimated to have died from the conflicts in the region since 2011. Moreover, as of the end of 2016, the region accounted for almost half of the world’s population of forcibly displaced people: 10 million refugees and 20 million internally displaced people from the region have had to abandon their homes. Syria alone has nearly 12 million displaced people, the largest number of any country in the region.

Conflict also reduces human capital by spreading poverty. Poverty in conflict countries, even outside regions directly affected by violence, tends to rise as employment declines. The quality of education and health services also deteriorates, a problem that deepens the longer a conflict continues. Syria provides a dramatic example. Unemployment jumped from 8.4 percent in 2010 to more than 50 percent in 2013, school dropout rates reached 52 percent, and estimated life expectancy fell from 76 years before the conflict to 56 years in 2014. Since then, the situation has deteriorated even more.

Second, physical capital and infrastructure are damaged or destroyed. Houses, buildings, roads, bridges, schools, and hospitals—as well as the water, power, and sanitation infrastructure—have been hit hard. In some areas, entire urban systems were virtually wiped out. In addition, infrastructure related to key economic sectors such as oil, agriculture, and manufacturing has been seriously degraded, with significant repercussions for growth, fiscal and export revenues, and foreign reserves. In Syria, more than a quarter of the housing stock has been destroyed or damaged since the war’s onset, while in Yemen, infrastructure damage has exacerbated drought conditions and contributed to severe food insecurity and disease. The country’s agricultural sector, which employed more than half the population, was hit hard, experiencing a 37 percent drop in cereal production in 2016 from the previous five-year average (UNOCHA 2017).

Third, economic organization and institutions are hurt. The deterioration in economic governance has been particularly acute where institutional quality was already poor before the outbreak of violence, as was the case in Iraq, Libya, Syria, and Yemen. This damage has led to reduced connectivity, higher transportation costs, and disruptions in supply chains and networks. Institutions can also become corrupt as the warring parties try to exert control over political and economic activity. Fiscal spending and credit, for example, might be redirected to the constituencies of those in power. More broadly, many critical economic institutions—central banks, ministries of finance, tax authorities, and commercial courts—have seen their effectiveness diminish because they have lost touch with the more remote parts of their countries. The World Bank estimates that disruptions to economic organization were about 20 times costlier than capital destruction in the first six years of the Syrian conflict (World Bank 2017).

Lastly, the stability of the region and its longer-term development through its impact on confidence and social cohesion are threatened. The conflicts in the Middle East and North Africa have heightened insecurity and reduced confidence, manifested by declining foreign and domestic investment, deteriorating financial sector performance, higher security spending, and shrinking tourism and trade. Social trust has also weakened, negatively affecting economic transactions and political decision making.

Direct and indirect effects

The macroeconomic damage can be staggering. Syria’s 2016 GDP, for example, is estimated to be less than half its 2010 preconflict level (Gobat and Kostial 2016). Yemen lost an estimated 25 to 35 percent of its GDP in 2015 alone, while in Libya—where dependence on oil has made growth extremely volatile—GDP fell by 24 percent in 2014 as violence picked up. The West Bank and Gaza offers a longer-term perspective on what can happen to growth in a fragile situation: its economy has been virtually stagnant over the past 20 years in contrast with average growth of nearly 250 percent in other countries of the region during that period (World Bank 2015).

Furthermore, these conflicts have led to high inflation and exchange rate pressures. In Iraq, inflation peaked at more than 30 percent during the mid-2000s; in Libya and Yemen it rose above 15 percent in 2011, on the back of a collapse in the supply of critical goods and services combined with strong recourse to monetary financing of the budget. Syria is an even more extreme case, with consumer prices rising by about 600 percent between 2010 and late 2016. Such inflation dynamics are usually accompanied by strong depreciation pressure on local currencies, which the authorities may try to resist through heavy intervention and regulation of cross-border flows. These forces have clearly been at work in Syria: the Syrian pound, which floated freely in 2013, officially trades at about one-tenth its prewar value against the US dollar.

Neighboring countries that are hosting refugees also feel economic pressure. Most directly affected are such countries as Turkey, which has taken in over 3 million people, a number equivalent to about 4 percent of its 2016 population; Lebanon, which has absorbed approximately 1 million, or roughly 17 percent of its population; and Jordan, which has seen an influx of 690,000 people, or 7 percent of its population (UNHCR 2017).

For these receiving countries, which invariably had economic challenges already, the refugee flows create additional pressure on budgets and the supply of food, infrastructure, housing, and health care. Countries bordering a high-intensity conflict zone in the Middle East and North Africa recorded a decline in average annual GDP growth of 1.9 percentage points, resulting in a growth rate too slow to provide enough jobs for the expanding population. For example, in Jordan, average annual real growth slowed to 2.6 percent between 2011 and 2016 from 5.8 percent between 2007 and 2010.

The effects of a heavy refugee influx can ripple throughout the economy. Evidence from Lebanon suggests that sizable informal employment among refugees, combined with depressed economic activity, has caused a drop in both wage levels and the labor force participation of locals, particularly women and young people. In Jordan’s Mafraq Governorate (an area in the northeast of the country that borders Syria), the rising demand for housing pushed up rents by 68 percent between 2012 and 2014—compared with 6 percent in Amman.

Managing multiple objectives

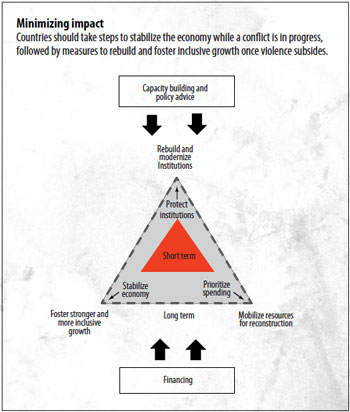

Macroeconomic policies and institutions have a significant role to play in lowering the impact of conflict, even when it is ongoing, both to alleviate the immediate harm and to improve the country’s long-term economic prospects (see Chart). While conflict is in progress, governments should focus on three priorities:

Protecting economic and social institutions from becoming inoperative or corrupt: This can help reduce the spread of poverty as well as support vital services. Disruptions to central banks, for example, could interfere with payment systems, which are essential for public sector salaries and for managing foreign reserves that pay for needed imports. An encouraging example is the Palestinian Monetary Authority’s business continuity planning, which was instrumental in maintaining a workable payment system and a robust macroprudential framework during periods of elevated stress, such as the 2014 tension in Gaza.

Prioritizing public spending to protect human life, limiting the rise in fiscal deficits, and, to the extent possible, helping to preserve economic growth potential: These policies try to tackle directly the challenges of damage to human and physical capital. Maintaining some fiscal discipline can reduce the government’s burden when the violence recedes. In Iraq, for example, the authorities are making plans with the World Bank and others to target public investment to geographical areas that have been retaken from ISIS following intense violence, with a view to achieving quick wins to improve public services, restore social cohesion, and lay the foundation for growth. In Afghanistan, the new government in 2002 and 2003 tried to maintain fiscal discipline and provide basic services to the population with the help of external assistance. It focused spending on security, education, health, and humanitarian assistance. The circumstances were extremely challenging given the loss of qualified staff at the Ministry of Finance following emigration during the years of war, the partial destruction of the ministry’s regional offices, and the damage to telecommunications and transportation infrastructure.

Stabilizing macroeconomic and financial developments through effective monetary and exchange rate policies: Appropriate policies can help contain inflation and exchange rate volatility, which exacerbate the hit to living standards. Lebanon offers a good example. Following the formation of a national unity government in 1989, the country’s economy remained fragile for some years. In 1992, authorities adopted an exchange-rate-based nominal anchor policy that targeted a slight nominal appreciation of the Lebanese pound against the US dollar. This policy successfully stabilized expectations, and inflation fell to single digits.

Unfortunately, experience in the region shows that these policy priorities are difficult to implement at times of sociopolitical fragility, when policymakers can be caught between multiple—and often competing—objectives.

Once conflict subsides, the policy focus should shift toward rebuilding and economic recovery. This has proved difficult, however, as countries are often still fragile even when the worst of the violence ends. Often governments do not have full control of all the territories within their borders, and security remains elusive. At such a time, economic policies should aim to solidify the peace. Rebuilding and modernizing institutions, mobilizing resources for reconstruction, and fostering stronger and more inclusive growth should be the top priorities. But the cost of reconstruction—particularly if conflicts in a region overlap—is often massive. While the reconstruction cost for Libya, Syria, and Yemen has yet to be assessed, the World Bank estimates the damage thus far to be on the order of $300 billion.

There is an important role for external partners in assisting countries that recover from conflict. Such partners, including the international financial institutions, can catalyze financing to the countries and even contribute some themselves, complementing domestic efforts to mobilize revenue. Countries embroiled in conflict inevitably need a large amount of capacity building support once the war is over, as well as financing for humanitarian purposes and reconstruction.

PHIL DE IMUS is a senior economist, GAËLLE PIERRE is an economist, and BJÖRN ROTHER is an advisor, all in the IMF’s Middle East and Central Asia Department.

This article draws on the IMF Staff Discussion Note “The Economic Impact of Conflicts and the Refugee Crisis in the Middle and North Africa.”

References

Gobat, Jeanne, and Kristina Kostial. 2016. “Syria’s Conflict Economy.” IMF Working Paper 16/123, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2017. Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2016. Geneva.

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA). 2017. “Yemen: Crisis Overview.” Geneva.

World Bank. 2015. “Economic Monitoring Report to the Ad Hoc Liaison Committee.” Working Paper 96601, World Bank, Washington, DC.

2017. “The Toll of War: The Economic and Social Consequences of the Conflict in Syria.” World Bank, Washington, DC.