Health in a Time of Austerity

Finance & Development, September 2017, Vol. 54, No. 3

Ramanan Laxminarayan and Ian Parry

When public budgets cannot grow, targeted taxes and subsidies can help improve a population’s well-being

Improving health care and increasing the number of people who are healthy may be a major development goal of the international community, but even in rapidly growing developing economies there is little capacity to increase spending on health per se, mainly because of the difficulty in raising more general tax revenue.

That constraint means that any additional funds for a health ministry would have to come from some other government ministry or project—a politically difficult, if not impossible, feat in low- and lower-middle-income economies.

Fortunately, many of the key factors that determine the health of a population—and how equally, or unequally, good health is shared among its citizens—lie outside of the health care system, and creative reform of taxes and subsidies can foster better health outcomes without big increases in spending on formal health programs.

Outside the system

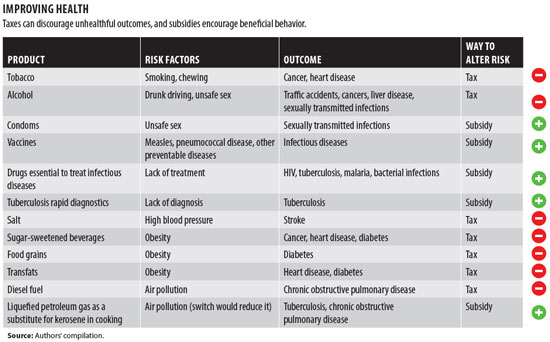

Among the factors outside the formal health system that determine well-being are access to clean water and sanitation; air quality; access to and use of toilets, soap, and condoms; walkability of neighborhoods; rates of tobacco and alcohol use; and nutritional intake, including consumption of sugar and refined grains. Many of these can be influenced by changes in taxes or shifts in subsidies.

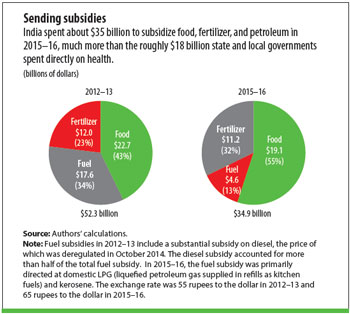

For example, commodities that harm health can be taxed while those that are beneficial can be subsidized. In India, subsidies for food, fertilizer, and petroleum—three commodities that can have large direct and indirect health effects—totaled about $52 billion in 2012–13 and $35 billion in 2015–16 (see chart). The subsidies in 2015–16 accounted for about twice what state and local governments spent directly on health. Taxes and tariffs can improve general population health when levied on commodities—such as alcohol, tobacco, salt, and sugar—that can harm people’s health. Subsidies on commodities such as sugar, diesel, kerosene, and coal could be reduced and the savings redirected to nutritious food and clean energy sources. Governments could subsidize liquefied natural gas, in place of kerosene for cooking, and fruit, dairy, and protein sources for nutrition (see table).

Tax lessons

Governments have long taxed tobacco and alcohol, and there are several lessons to be learned from their experiences using levies to affect healthy behavior:

Taxes, and the concomitant price increases they trigger, must be substantial to achieve the desired changes in consumption. Excise taxes, with periodic adjustments for inflation, can be effective.

Governments must prevent domestic and regional efforts to avoid the tax by closing loopholes and guard against smuggling and bootlegging, because large tax increases are so important to achieving results. At the regional level, policymaking and enforcement must be coordinated, especially for tobacco products, which are quite easy to transport and trade illegally.

The design of taxes must take into account the range of relevant products and the changes in consumption consumers might make if a tax is imposed in only one area—for example if sugar-sweetened beverages are taxed, consumers might instead eat salty, high-fat snacks if those were untaxed.

Young people and low-income populations tend to respond most to price increases on unhealthy foods and beverages, tobacco, and alcohol.

Consideration could be given to allocation of a portion of revenues to fund subsidy programs that improve nutrition, air quality, and active living to reduce the incidence of heart disease, stroke, and diabetes.

From an economic standpoint, taxes on tobacco, alcohol, and sugar are justified not only to address the bad effects on society from the abuse of these substances, but also to raise government revenue. In previous work, we have shown that the revenue-raising component of the optimal alcohol tax may be as large, or larger, than the component that mitigates the bad effects of alcohol abuse (Parry, West, and Laxminarayan 2009). Therefore, fiscal considerations can significantly strengthen the case for higher alcohol taxes. In a similar vein, reorienting subsidies could give countries facing constraints on raising other taxes some spending breathing room.

Food substances that contribute to obesity—including refined grains such as white flour and white rice—are heavily subsidized in many countries. With obesity on the rise, these subsidies should be reoriented toward improving the nutritional content of subsidized food. In India, production and consumption of pulses (basically dried legumes) have stagnated, while the output of food grains and sugar has increased. in India, under the National Food Security Act, passed in 2013, the government is projected to spend $25 billion a year to subsidize food grains. While this subsidy could improve food security for some households, spending these funds on public subsidies of pulses, fruits, vegetables, and milk would have a far greater beneficial impact on nutrition.

Clean air counts

It is not only what consumers eat, drink, or smoke that can harm health and whose effects can be modified by taxes or subsidies. Nearly every country subsidizes coal, gasoline, and diesel—and these fossil fuels are the leading producers of particulate matter, which causes lower respiratory tract infections, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cancers, and heart disease and exacerbates the risk of tuberculosis. According to a 2015 IMF working paper, “How Large Are Global Energy Subsidies?,” governments spent $5.3 trillion in 2015 to subsidize energy—the equivalent of 6.5 percent of the world’s GDP. Energy subsidies exceeded public spending on health and education in many countries—including Bangladesh, Indonesia, and Pakistan. Subsidies have declined recently, although much of this is attributable to the global decline in diesel prices during the past five years. Reallocating fuel subsidies toward clean fuels and eliminating subsidies on those that are dirtiest could improve people’s health substantially and help cash-strapped governments at the same time.

Pushback

There are two sets of pressures that push back against the use of taxes and subsidies as instruments of health policy. First, removal of subsidies and imposition of taxes are often portrayed as being anti-poor and not politically popular. However, the health and economic burden of tobacco and alcohol use falls heaviest on the poor. Across the world, heart disease and stroke are the leading causes of catastrophic expenditures, and in countries such as India such expenditures are the main reason families fall into poverty (van Doorslaer and others 2006).

A second concern is that removal of agricultural subsidies would hurt farmers and small-scale manufacturers, including those that make cheap thin-rolled cigarettes called bidis. While it is true that farmers of sugarcane and tobacco do well financially in many countries, the solution is not to put them out of business but to assist them in a transition to growing crops that are not harmful to human health. Allocating tax revenue and reorienting subsidies toward health-improving fiscal policies could have a double benefit. But for this to happen policymakers must make explicit their reasons for tax increases and subsidy reallocations and show how the losers from these policy changes will be compensated to ensure that their livelihoods are not compromised.

Low- and middle-income countries must deal with a growing burden of noncommunicable diseases—including cancer and heart disease—while maintaining vigilance against childhood and infectious diseases. As countries grow, the health needs of their populations will increase. By using economic incentives to modify social determinants of health, countries could bring about significant improvements without breaking the bank.

RAMANAN LAXMINARAYAN is director of the Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy. IAN PARRY is the principal environmental fiscal policy expert in the IMF’s Fiscal Affairs Department.

References

Parry, Ian W. H., Sarah E. West, and Ramanan Laxminarayan. 2009. “Fiscal and Externality Rationales for Alcohol Policies.” B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy 9 (1).

van Doorslaer, Eddy, and others. 2006. “Effect of Payments for Health Care on Poverty Estimates in 11 Countries in Asia: An Analysis of Household Survey Data.” Lancet 368 (9544): 1357–64.