Transmission Troubles

Finance & Development, September 2016, Vol. 53, No. 3

Adolfo Barajas, Ralph Chami, Christian Ebeke, and Anne Oeking

Heavy inflows of remittances impair a country’s ability to conduct monetary policy

Many developing and emerging market economies are modernizing the way they conduct monetary policy to make it more transparent and forward looking, with more emphasis on exchange rate flexibility, an explicit inflation objective, and greater reliance on a short-term interest rate as the policy instrument.

But to be successful these countries must have an operable “transmission mechanism” that permits changes the central bank makes in the policy rate to propagate through the economy and ultimately affect spending decisions by households and firms. Several recent studies find that this transmission mechanism is missing or severely weakened in lower-income countries.

We have found the same weakened transmission mechanism in middle-income and emerging market economies that are major recipients of remittances—that is, money citizens living abroad send home to their families. That means policymakers in those economies should be aware of the difficulties they face in pursuing a fully modern monetary policy, and they may want to consider measures to strengthen the transmission mechanism or other approaches to help them conduct monetary policy.

Remittances are large and growing

International inflows of workers’ remittances are a fixture in many developing and emerging market economies. Worldwide, official measures of these flows have been on a steady upward trend, from negligible amounts in 1980 to approximately $588 billion in 2015—$435 billion of which were received by developing economies. As a source of foreign funds in recent years, workers’ remittances have amounted to close to 2 percent of GDP on average for all emerging market and developing economies, while foreign direct investment (FDI) represented 3 percent, portfolio investment amounted to nearly 1 percent, and official transfers (foreign aid) were just over ½ percent. In 2014, some 115 countries received remittances equivalent to at least 1 percent of GDP, and 19 countries received 15 percent or more. Compared with private capital or official aid flows, remittances have been more stable—their cyclical volatility has proved to be appreciably lower—and they suffered a much milder contraction following the global financial crisis that started in 2008.

In some countries, remittances dwarf other external flows. For example, in 2015 in Jordan—among the top 30 recipients in recent years—remittance inflows amounted to about 9 percent of its GDP, more than 4 times FDI inflows and 3½ times private Eurobond placements.

While it is undeniable that remittances bring tangible benefits to the receiving country, supporting income and consumption of remitters’ families back home, it is also to be expected that flows of this magnitude year after year would have sizable effects on the overall economy—not all of them necessarily beneficial. A survey of economic research (Chami and others, 2008) found that remittances have measurable effects on exchange rates, the sustainability of tax and spending (fiscal) policy, institutions and governance, long-term economic growth, and monetary policy. Several studies have shown that persistent inflows of remittances exert upward pressure on the long-term real exchange rate, which makes the goods that the recipient economy exports more expensive. Beyond their effect on exchange rates and tradable exports, these flows are a channel that can transmit shocks from remittance-sending to remittance-receiving countries, which links their business cycles. During the recent global crisis, for example, sharp downturns in advanced (sending) economies were transmitted to low- and middle-income (recipient) economies as workers were forced to cut back on the funds they could send to their families (Barajas and others, 2012). More recently, the decline in oil prices has resulted in similar transmission from oil-producing countries in the Persian Gulf to their corresponding recipient countries, mainly oil importers of the Middle East and North Africa region.

When it comes to fiscal policy, there can be both positives and negatives for a country that receives a large and steady stream of remittances over time. Remittances directly expand the tax base, which makes it easier for countries to maintain fiscal sustainability, in the sense of avoiding a situation of ever-expanding public debt. However, remittances can also skew the behavior of governments, in undesirable ways. First, and somewhat paradoxically, the very expansion in the revenue base could distort government incentives, lowering the costs of engaging in wasteful spending. Second, the supplemental income that remittances provide to households increases their ability to purchase goods that substitute for government services and reduces their incentive to hold the government accountable.

Effect on monetary policy

Most studies exploring remittances presume a well-functioning financial system and an operable transmission mechanism, conditions that may not exist in those countries. In other words, the studies assume that when policymakers change a policy interest rate, the change is passed on effectively to other rates in the economy, ultimately affecting lending behavior by financial intermediaries and spending decisions by households and firms.

We explored whether this is an accurate representation of the monetary policy environment in countries that are major recipients of remittances. If the transmission mechanism is absent in recipient countries, then policymakers will face an additional difficulty in conducting independent and forward-looking monetary policy using an interest rate instrument (Barajas and others, 2016).

For low-income countries, there is growing evidence that monetary policy transmission is substantially weaker than in advanced economies. While a variety of transmission channels may operate, Mishra, Montiel, and Spilimbergo (2012) argue that weak securities market development, imperfect integration with international financial markets, and highly managed exchange rates are likely to leave poorer countries with only one operable channel—bank lending. A change in the policy rate ripples through markets for short-term securities, ultimately affecting banks’ cost of funds at the margin and thus their ability to lend to private entities, whether people or firms.

However, even the bank-lending channel may be seriously weakened if there is little banking competition, the quality of institutions is poor, interbank markets in which banks deal with each other are underdeveloped, and information is lacking about the quality of borrowers. These factors conspire to short-circuit the transmission of moves in the short-term policy rate to banks’ cost of funds.

Remittances, which are common not only in low-income but also in a variety of middle-income and emerging market economies, can also affect the conduct of monetary policy, in two ways. First, remittances expand bank balance sheets by providing a stable and essentially costless source of deposits—because they are largely insensitive to interest rates. All other conditions equal, recipient countries tend to have larger banking systems. Thus, because the remittance deposits increase the amount of financial intermediation (the process of banks matching up savers and borrowers), remittances might be expected to contribute to stronger monetary policy transmission. After all, the more financial services are used throughout an economy, the stronger the expected effect of fluctuations in bank credit on economic activity.

On the other hand, although banks might receive ample and virtually costless additional funding year after year from deposited remittances, that does not mean they will increase lending to the private sector one for one. Remittance-recipient economies—such as economies in most of the developing world—are often plagued by a number of problems, including a weak institutional and regulatory environment and a dearth of creditworthy borrowers. In fact, as we said, remittance flows may have a hand in weakening governance. This fragile lending environment reduces banks’ willingness to lend beyond a very limited pool of “qualified” borrowers, a reluctance that the additional lendable funds do nothing to counteract. Banks in recipient countries, then, tend to hold larger shares of liquid assets, excess reserves, and government securities than banks in nonrecipient countries (see Chart 1). As a result, because banks are flush with liquidity, an interbank market—in which institutions in need of short-term funds borrow from those with excess balances—fails to develop. Because the policy rate is designed to affect the marginal cost of funds for banks, when there is virtually no interbank market, the effect of policy rate movements is weakened or nonexistent. The bank lending channel becomes impaired.

Weaker monetary transmission

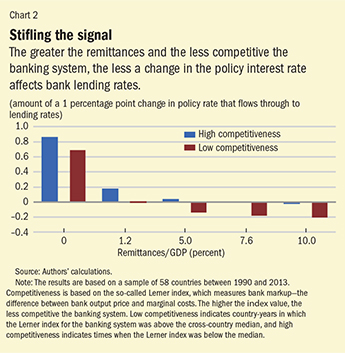

Our empirical analysis confirms that, as remittances increase, monetary transmission through the bank lending channel weakens notably. Based on a sample of 58 countries worldwide between 1990 and 2013, we find that the strength of transmission, measured as the direct effect of a change in the policy rate on changes in bank lending rates, declines continuously as the size of remittances increases. In countries that do not receive remittances and have competitive banking systems, nearly 90 percent of a change in the policy rate is transmitted to the bank lending rate. In contrast, in an economy that receives 5 percent of GDP annually in remittances, only about 4 percent of the same change to the lending rate is transmitted, even when banking systems are competitive. In fact, when remittances reach 7.6 percent of GDP, the policy rate has no effect on bank lending rates. If the banking system is not competitive, the turning point occurs at a much lower level of remittances—1.2 percent of GDP (see Chart 2).

The so-called trilemma policy framework posits that when a country freely allows capital to flow in and out of its economy and maintains a fixed exchange rate, its ability to conduct an independent monetary policy is seriously impaired. Attempts by policymakers to affect the domestic interest rate tend to induce rapid and large capital flows (either into or out of the country, depending on whether interest rates are raised or lowered) that ultimately undo the policy action. Our results suggest that a parallel trilemma may arise when remittances are present, but for a different reason. Unlike capital flows, remittances do not respond to changes in domestic interest rates. Their continued presence weakens monetary policy, not because policymakers cannot affect domestic interest rates, but because the authorities’ policy rate is unlikely to be transmitted to decisions affecting domestic economic activity. Thus, remittance-recipient countries may opt to scale back plans for full monetary policy independence. In fact, research suggests that greater remittance inflows are indeed associated with greater intervention in foreign currency markets, whether to fully fix the exchange rate or manage its fluctuations.

Policy options

This finding may lead to the conclusion that, short of abandoning monetary independence, a recipient country should target remittances, given that their continued presence is at least partly responsible for weakening the impact of monetary policy. In particular, there might be a temptation to try to control or curtail remittance inflows. However, it would be impractical to enforce reductions in remittance inflows—transfers would not stop but would move to the parallel market—and curtailment would rob the economy of the poverty-reduction and insurance effects of remittances on the recipient households.

Instead countries could explore alternatives to short-term interest rates, while still moving to a more transparent and forward-looking framework. An option might be to require that the deposits (reserves) banks maintain with the central bank be high enough to become binding, thereby restoring some control over bank lending. Of course, this would come at the cost of a reduction in private sector credit. Another option might be to tax banks’ excess liquidity (cash or assets that can easily be converted to cash, such as government securities), which would encourage them to lend more. However, such an approach might increase credit risk—what banks were trying to avoid by restricting their pool of borrowers.

The best approach would be to target the root factors—such as low institutional quality and lack of complete information about the dependability of borrowers—that cause banks to accumulate excess liquidity rather than expand private sector credit beyond their well-known borrowers. Realistically, however, this would take a long time to achieve. Structural reforms—such as enforcing property rights, enhancing the rule of law, and combating corruption—could also play an important role. These measures would also help rein in fiscal deficits—reducing the need for governments to borrow from banks, which would free up resources to finance the credit-strapped private sector. ■

Ralph Chami is an Assistant Director and Adolfo Barajas is a Senior Economist, both in the IMF’s Institute for Capacity Development. Christian Ebeke is an Economist in the IMF’s European Department, and Anne Oeking is an Economist in the IMF’s Finance Department.

Reference

Barajas, Adolfo, Ralph Chami, Christian Ebeke, and Anne Oeking, 2016, “What’s Different about Monetary Policy Transmission in Remittance-Dependent Countries?” IMF Working Paper 16/44 (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

Barajas, Adolfo, Ralph Chami, Christian Ebeke, and Sampawende J. Tapsoba, 2012, “Workers’ Remittances: An Overlooked Channel of International Business Cycle Transmission?” IMF Working Paper 12/251 (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

Chami, Ralph, Adolfo Barajas, Thomas Cosimano, Connel Fullenkamp, Michael Gapen, and Peter Montiel, 2008, Macroeconomic Consequences of Remittances, IMF Occasional Paper 259 (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

Mishra, Prachi, Peter Montiel, and Antonio Spilimbergo, 2012, “Monetary Transmission in Low-Income Countries: Effectiveness and Policy Implications,” IMF Economic Review, Vol. 60, No. 2, pp. 270–302.

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect IMF policy.