The Long Run Is Near

Finance & Development, September 2010, Vol. 47, No. 3

Kevin Cheng, Erik De Vrijer, and Irina Yakadina

France, like many advanced economies, confronts the expensive needs of a rapidly aging population

FRANCE has begun to recover from the Great Recession earlier than most advanced European economies. However, weak domestic demand, as well as the slow recovery in its main trading partners in Europe and elsewhere, has resulted in a sluggish rebound with high unemployment. Turbulence in European debt markets and the possible spillovers are also weighing on the short-term economic outlook.

But if the near-term prospects are less than stellar, the longer-term fiscal prospects are perhaps more clouded. Not only are public finances feeling the adverse effects of the recession, an aging population with its attendant health and pension costs will put increasing pressure on France’s fiscal future—as they will in most advanced economies (see “How Grim a Fiscal Future?” in this issue of F&D).

The government is left with a delicate balancing act. On the one hand, it is wary of taking steps to reduce the budget deficit too rapidly for fear of derailing the fragile recovery. On the other, it cannot delay instituting policies that aim at getting revenue and spending in line over the longer term. The government has announced a sizable fiscal consolidation over 2011–13 to pave the way for such fiscal sustainability. Among the items in this medium- and long-term consolidation is a politically controversial reform of the pension system.

A weakened fiscal position

France’s fiscal challenges have both acute and chronic causes. The acute dimension is the recession, which exacted a large toll, both direct and indirect, on public finances. The direct impact includes the cost of the fiscal stimulus package that replaced private demand with public demand and support for the financial sector. The indirect impact includes the crisis-related revenue loss (mainly taxes and social security contributions), the cost of automatic stabilizers (such as unemployment benefits), and the loss in output—which makes the public debt larger relative to the national income.

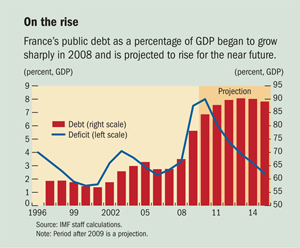

As a result of the crisis, France’s fiscal position has weakened (see chart). After shrinking from 4.1 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2003 to 2.3 percent in 2006, the overall deficit began to climb again in 2007, and spending is expected to exceed revenue by about 8 percent of GDP in 2010. Under current policies, the ratio of public debt (which represents accumulated deficits) to GDP could grow within a few years by more than 25 percentage points above its pre-crisis level—to 90 percent of GDP.

Population aging is the most deep-seated of the chronic issues confronting France. According to a study by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), France’s old-age dependency ratio—the ratio of citizens over age 65 to the working-age population—was about 27 percent in 2007. This ratio is projected to rise to 42 percent by 2025 and 58 percent by 2050. This is a serious aging problem shared by other advanced economies. Likewise, the number of persons between ages 20 and 64 for every person over age 65 is expected to decline from 3.5 in 2010 to just 2 by 2040, increasing pressure on the current pay-as-you-go pension system. Simply put, the elderly are going to consume an increasingly large amount of France’s resources. Large-scale retirements have already begun and will likely intensify in the years to come.

But it is not just demographics that cause the old-age fiscal burden. A number of features of France’s pension system are also at play. First, public transfers—in the form of pensions and safety-net benefits—provide more than 85 percent of the income for people over age 65. This is the second highest level in OECD countries, where the average is about 60 percent. Given that French public finances have been in deficit over the past 30 years, increasing deficits in the pension system aggravate the fiscal concerns. Second, France’s current legal retirement age is 60 years, which is among the lowest in the European Union. Consequently, French people have the longest retirement in Europe, averaging 28 years for women and 24 for men. That long payout period exacerbates the problem.

Without significant changes in policy, large spending pressures from pensions, as well as the rising health costs that accompany an aging population, will require increased public spending and borrowing to support that spending—raising public debt to unsustainable levels over the longer term. But it is not only health and pensions that burden France’s fiscal future. Over the past decade, local government spending has been growing quickly, partly due to an extensive fiscal decentralization process. The government is taking steps to limit that growth.

France’s policy options

Maintaining the status quo is not an attractive option. The potential fiscal consequences are too grave. Policies that aim at streamlining public spending in the medium and long term while protecting expenditures that help maintain domestic demand are in order. Such policies, which in economic parlance are aimed at achieving “fiscal sustainability,” should focus on three areas.

- Pension reform. The government has proposed major pension reforms aimed at achieving financial equilibrium by 2018. It is an ambitious goal because the deficit in the pensions system now is almost 1.5 percent of GDP. The reform, which the National Assembly must approve, would overhaul the system in a number of ways. It would gradually raise the legal retirement age from 60 to 62 years, a measure that is opposed by the labor unions. Full pension benefits, now available at age 65, would be pushed back until age 67. The proposed changes would also raise the ceiling on social contributions for high-income earners, remove some contribution exemptions, and gradually align the pension system of civil servants with that of the private sector. The government has already lengthened the contribution period from 37.5 to 41 years, effective in 2012. These measures, taken together, would lead to a tangible increase in the effective retirement age and allow for better synchronizing retirement policies with life expectancy at retirement.

- Health care. A number of measures have been proposed to limit hospital and drug costs and to better enforce the planned reduction of the existing national spending norm. In contrast to the proposed pension changes, the health care reform agenda is still being developed, and significant further modifications will be needed to contain medical spending without jeopardizing the quality of medical services.

- Controlling local government spending. The decentralization that began in the 1980s brought rapid growth in local government spending and increasing transfers from the central government. A freeze on central government transfers to local governments that will start in 2011 could encourage efficiency gains, including by reducing the duplication of responsibilities for different layers of government.

Needed: a fiscal rule

Under any circumstances, the requisite fiscal restraint will be difficult to achieve. Enhanced fiscal discipline would help. Toward that end, a so-called fiscal rule—a permanent constraint on taxing and spending policies, typically defined in terms of an indicator of overall fiscal performance—would significantly strengthen the credibility of the announced fiscal consolidation. Such a rule would lock in France’s commitment to achieving equilibrium in its public finances and could instill discipline at all levels of government. In addition, France’s adoption of a fiscal rule would likely strengthen the implementation of the Stability and Growth Pact—the European agreement that caps a country’s deficit at 3 percent of GDP and its public debt at 60 percent of GDP—and boost fiscal discipline in the euro area, given France’s prominent role.

In June, a working group on fiscal rules—headed by former IMF Managing Director Michel Camdessus—proposed to enshrine in the constitution a strengthened multiyear budgetary framework (see “By the Rule” in this issue of F&D). Such a framework would include a binding trajectory toward a zero structural deficit—the government deficit adjusted for the business cycle—of the general government and reinforce national belief in the fiscal objectives of France’s stability programs. The working group also called for creation of an independent fiscal council to increase the realism of the macroeconomic assumptions underlying the budgetary framework and to strengthen the government’s accountability.

A sizable consolidation over the coming years is needed to keep France’s public finances sound. Although this is challenging, such an adjustment can be achieved provided the country can muster a strong public belief in and commitment to the medium- and long-term fiscal objectives.