Sub-Saharan Africa stands to gain more from reducing corruption than any other region

A new wave of leaders in sub-Saharan Africa has expressed renewed commitment to fighting corruption. This trend reflects a recognition that good governance is key to fostering growth and economic development. The link between growth and governance is especially strong on this resource-rich continent, where people stand to gain more economically from reducing corruption than anywhere else in the world.

Our research shows that the governance dividend for countries in sub-Saharan Africa is two to three times larger than for the average country in the rest of the world—even in regions perceived to have equally weak governance. Bringing sub-Saharan Africa’s governance to the world average could increase GDP per capita by an estimated 1 to 2 percentage points a year.

Low corruption and good governance are not the sole drivers of growth, of course. Some countries perceived as having weak governance have experienced episodes of strong growth driven by other factors—for example, natural resource wealth. In other cases, countries with good governance have not necessarily enjoyed strong growth. But we find that corruption tends to undermine economic growth, behaving more like sand than oil in the economic engine.

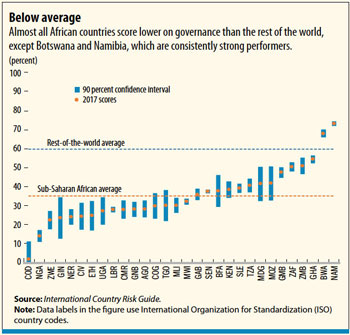

The governance landscape varies significantly around the world, with most developing regions performing poorly. Sub-Saharan Africa is a case in point: only 2 of the 30 countries from the region included in the International Country Risk Guide’s 2017 governance index scored above the average for the rest of the world (see chart).

Some African governments are already showing a clear commitment to fighting corruption and strengthening governance. For instance, various segments of the South African government apparatus and institutions were made subservient to a select group of people during the so-called state capture episode. Since 2018, the government has been engaged in a bold fight to reverse the damage by improving procurement, fighting smuggling, and rebuilding the capacity of critical institutions such as the revenue authority and the anti-corruption agency.

Similarly, Angola had lost control over billions of dollars from its sovereign wealth fund. The money was siphoned off by a rogue fund manager, with others complicit, through complex financial transactions moving through offshore financial centers and invested in ventures of personal interest. The new Angolan government elected in 2017 changed the management and placed the previous management under investigation. The fund’s assets have since been recovered and are now being reinvested for the benefit of the Angolan people.

In other instances, however, retrograde processes such as kickbacks in the allocation of uncompetitive oil and gas contracts and the expropriation of private assets are still in place, undermining the sanctity of property rights and the rule of law, with damaging effects on investment and growth. In a few cases, the independence of central banks is under attack from politicians seeking expedient solutions to finance the budget or boost growth through monetary easing instead of reforms.

Improving governance is difficult, as the beneficiaries of corruption often fight back. It is a complex, drawn-out battle among the various players—government, institutions, civil society, media, and the private sector. Strong political commitment is thus an absolute requirement for success.

Conventional policies

From an economic perspective, there are some basic principles that apply across countries and can boost governance, such as strengthening laws, improving government effectiveness, and shoring up fiscal and anti-corruption institutions.

In countries such as Botswana, Chile, Estonia, and Georgia that have managed to lower corruption, multiple factors contributed to their success. These include political will, measures to reduce corruption opportunities (such as cutting red tape and lowering trade barriers), measures to constrain corrupt behavior (such as an independent judicial system or a strong anti-money laundering framework), and improved fiscal institutions (with greater transparency and controls).

Building expertise and empowering employees in institutions designed to fight corruption will improve their prosecution capability and bridge the gap between public opinion and the court of law. Corruption prosecution cases often fail when governments lack adequate legal capacity. Enhancing corporate governance and a system of checks and balances, particularly through a better governance structure for state-owned enterprises, will also help.

How is governance measured?

Governance is a multifaceted issue cutting across politics, economics, and institutions. The indicators with the most significant economic ramifications include corruption (abuse of public office for private gain), government effectiveness (quality of public policies and services), regulatory quality (ability of the government to formulate and implement business-friendly policies and regulations), and the rule of law (respect for contract enforcement, property rights, and law enforcement).

Bringing the various governance dimensions into one indicator can be challenging, as aggregating subjective measures may not fully capture the reality on the ground, either due to cultural differences—corruption in one country may be a customary practice in another—or the fact that distinct attributes of governance are lumped together in one indicator. While corruption perceptions tend to be the main component of interest, most measurements are broad enough to be useful proxies for the quality of political institutions, government regulations, and policies.

Institutional reform takes time, but more rigorous enforcement of existing regulations would be a step in the right direction.

Digitalization is opening up new ways of fighting corruption by providing governments with new platforms for engaging with citizens and entrepreneurs. It also promotes greater transparency and accountability by facilitating access to information. Many African countries are using this opportunity to improve service delivery and governance in a variety of ways.

In the area of taxation, for example, electronic processing of tax submissions, refund payments, and customs declarations saves time and lowers costs—as well as reducing corruption opportunities. Data analytics make risk-based auditing possible, allowing for faster processing of tax claims.

Digitalization can also improve spending efficiency. Biometric technologies and electronic payment systems are helping cut bureaucratic inefficiencies, better target people in need, produce fiscal savings, and facilitate the delivery of benefits. People are using digital payments—for example, for school fees—to reduce the scope for fraud and corruption by bypassing public officials.

Digitalization can also make procurement more transparent, inclusive, and efficient. Centralized procurement can reduce conflicts of interest and abuse, including at the level of state-owned enterprises, provinces, and local governments.

Concrete benefits

What exactly would this governance dividend mean for the people of sub-Saharan Africa? Better governance and less corruption would result in more revenue for the government, more efficient use of this revenue, increased private investment and job opportunities, and more money to spend and invest in services vital to long-term development, such as health and education. We would expect it to bear fruit in a few different ways:

● Enhanced revenue collection through improved tax compliance. Customs and revenue authorities are better able to combat smuggling and illicit flows when tax officials adhere to strong governance principles. Citizens are more likely to pay their taxes when they trust the effectiveness of government spending.

● More efficient government spending thanks to stronger budgetary processes. Good governance reduces the risk of harmful shifts in government spending toward items subject to graft (white elephants, for instance).

● Improved developmental outcomes and social inclusion. More revenue overall means governments can spend more on their people. Improved governance is likely to benefit the poor disproportionately as they rely more on social services. And increased spending on education and health supports economic and social inclusion and reduces vulnerability.

The continent is at a turning point, reflecting a confluence of factors. A young population with access to real-time information through digitalization and open-access data is demanding transparency and accountability from elected officials. Moreover, to attract foreign investment and integrate with the global economy, countries will need to adhere to good governance principles. Irrespective of the path countries choose to improve governance, the dividends that result will be significant and worth pursuing. Good governance is more relevant than ever.

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect IMF policy.