World Economic Outlook

Uncertainty in the Aftermath of the U.K. Referendum

July 2016

[$token_name="PublicationDisclaimer"]

Reports and Related Links:

- Before the June 23 vote in the United Kingdom in favor of leaving the European Union, economic data and financial market developments suggested that the global economy was evolving broadly as forecast in the April 2016 World Economic Outlook (WEO). Growth in most advanced economies remained lackluster, with low potential growth and a gradual closing of output gaps. Prospects remained diverse across emerging market and developing economies, with some improvement for a few large emerging markets—in particular Brazil and Russia—pointing to a modest upward revision to 2017 global growth relative to April’s forecast.

- The outcome of the U.K. vote, which surprised global financial markets, implies the materialization of an important downside risk for the world economy. As a result, the global outlook for 2016-17 has worsened, despite the better-than-expected performance in early 2016. This deterioration reflects the expected macroeconomic consequences of a sizable increase in uncertainty, including on the political front. This uncertainty is projected to take a toll on confidence and investment, including through its repercussions on financial conditions and market sentiment more generally. The initial financial market reaction was severe but generally orderly. As of mid-July, the pound has weakened by about 10 percent; despite some rebound, equity prices are lower in some sectors, especially for European banks; and yields on safe assets have declined.

- With “Brexit” still very much unfolding, the extent of uncertainty complicates the already difficult task of macroeconomic forecasting. The baseline global growth forecast has been revised down modestly relative to the April 2016 WEO (by 0.1 percentage points for 2016 and 2017, as compared to a 0.1 percentage point upward revision for 2017 envisaged pre-Brexit). Brexit-related revisions are concentrated in advanced European economies, with a relatively muted impact elsewhere, including in the United States and China. Pending further clarity on the exit process, this baseline reflects the benign assumption of a gradual reduction in uncertainty going forward, with arrangements between the European Union and the United Kingdom avoiding a large increase in economic barriers, no major financial market disruption, and limited political fallout from the referendum. But—as illustrated in Box 1— more negative outcomes are a distinct possibility.

- This WEO Update briefly elaborates on these themes and their implications for policymakers. A more thorough assessment of the global outlook will be presented in the October 2016 WEO.

Recent Developments

The recovery in financial and oil markets that started about mid-February broadly continued through June 23, as markets assumed the United Kingdom would remain in the European Union.

Declines in excess oil supply—due mainly to a gradual slowdown in non-OPEC production and some supply disruptions (notably in Nigeria and Canada)—helped bolster oil prices. This was reflected in an easing of oil exporters’ sovereign bond spreads from their February-March highs. Bond yields in the main advanced economies declined further, reflecting compressed term premia as well as expectations of a more gradual pace of monetary policy normalization, while stock market valuations remained broadly steady.

Turning to indicators of real activity, output growth in the first quarter of 2016 was somewhat better than expected in emerging market and developing economies and roughly in line with projections for advanced economies, with better-than-expected euro area growth counterbalancing weaker U.S. growth. Productivity growth in most advanced economies remained sluggish, and inflation was below target owing to slack and the effect of past declines in commodity prices. Indicators of real activity were somewhat stronger than expected in China, reflecting policy stimulus, as well as in Brazil and Russia, with some tentative signs of moderation in Brazil’s deep downturn and stabilization in Russia following the rebound in oil prices. While global industrial activity and trade have been lackluster amid China’s rebalancing and generally weak investment in commodity exporters, recent months have seen some pick-up due to stronger infrastructure investment in China and higher oil prices.

These data, together with financial market developments in the months before the referendum, indicated a global economic outlook broadly in line with the April 2016 WEO forecast, with some improvement of the outlook for a few large emerging markets even pointing to a modest upward revision to global growth for 2017 (0.1 percentage point).

The result of the U.K. referendum caught financial markets by surprise. In its immediate aftermath, equity prices declined worldwide. These prices have since rebounded, although as of mid-July bank equity valuations for U.K. and European banks remain substantially lower than before the referendum, and domestically focused U.K. equities are slightly weaker. Yields on safe assets have declined further, reflecting both higher global risk aversion and expectations of easier monetary policy going forward, particularly in the main advanced economies. The pound depreciated sharply—by around 10 percent in nominal effective terms between June 23 and July 15—with more limited changes for other major currencies. The prices of oil and other commodities declined moderately, but have remained well above those underpinning the assumptions for the April 2016 WEO.1 Post-referendum asset price and exchange rate movements in emerging markets have been generally contained.

From a macroeconomic perspective, the Brexit vote implies a substantial increase in economic, political, and institutional uncertainty, which is projected to have negative macroeconomic consequences, especially in advanced European economies. But with the event still unfolding, it is very difficult to quantify its potential repercussions.

The baseline global growth forecasts for 2016 and 2017 (Table 1) reflect the benign assumption of a gradual reduction in uncertainty going forward. In this scenario, arrangements between the European Union and the United Kingdom settle so as to avoid a large increase in economic barriers (as outlined in the “limited scenario” in the IMF’s 2016 United Kingdom Staff Report); no major financial market disruption occurs; and political fallout from the referendum is limited. But these benign assumptions may fail to materialize and—as illustrated in Box 1—more negative outcomes are a distinct possibility.

Taking into account the better-than-expected economic activity so far in 2016 and the likely impact of Brexit under the assumptions just described, the global growth forecasts for 2016 and 2017 were both marked down by 0.1 percentage points relative to the April 2016 WEO, to 3.1 percent and 3.4 percent, respectively. The outlook worsens for advanced economies (down by 0.1 percentage points in 2016 and 0.2 percentage points in 2017) while it remains broadly unchanged for emerging market and developing economies.

- Among advanced economies, the United Kingdom experienced the largest downward revision in forecasted growth. While growth in the first part of 2016 appears to have been slightly stronger than expected in April, the increase in uncertainty following the referendum is projected to significantly weaken domestic demand relative to previous forecasts, with growth revised down by about 0.2 percentage points for 2016 and by close to 1 percentage point in 2017.

- In the United States, first-quarter growth was weaker than expected, triggering a downward revision of 0.2 percentage points to the 2016 growth forecast. High-frequency indicators point to a pick up in the second quarter and for the remainder of the year, consistent with fading headwinds from a strong U.S. dollar and lower energy sector investment. The impact of Brexit is projected to be muted for the United States, as lower long-term interest rates and a more gradual path of monetary policy normalization are expected to broadly offset larger corporate spreads, a stronger U.S. dollar, and some decline in confidence.

- In the euro area, growth was higher than expected at 2.2 percent in the first quarter, reflecting strong domestic demand—including some rebound in investment. While high-frequency indicators point to some moderation ahead, the growth outlook would have been revised up slightly relative to April for both 2016 and 2017 were it not for the fallout from the U.K. referendum. In light of the potential impact of increased uncertainty on consumer and business confidence (and potential bank stresses), 2017 growth was revised down by 0.2 percentage points relative to April, while 2016 growth is still projected to be slightly higher, given outcomes in the first half of the year. Delays in tackling legacy issues in the banking sector, however, continue to pose downside risks to the forecast.

- First-quarter activity in Japan came in slightly better than expected—even though the underlying momentum in domestic demand remains weak and inflation has dropped. With the announced delay in the April 2017 consumption tax hike to October 2019, the growth forecast for 2017 would have been raised by some 0.4 percentage points next year. However, the further appreciation of the yen in recent months is expected to take a toll on growth in both 2016 and 2017: as a result, the growth forecast for 2016 has been reduced by about 0.2 percentage points, and the upward revision to growth in 2017 is now projected to be only 0.2 percentage points. Japan’s growth in 2017 could be higher if, as expected, a supplementary budget for fiscal year 2016 is passed, providing more fiscal support.

- In China, the near-term outlook has improved due to recent policy support. Benchmark lending rates were cut five times in 2015, fiscal policy turned expansionary in the second half of the year, infrastructure spending picked up, and credit growth accelerated. The direct impact of the U.K. referendum will likely be limited, in light of China’s low trade and financial exposure to the United Kingdom as well as the authorities’ readiness to respond to achieve their growth target range. Hence, China’s growth outlook is broadly unchanged relative to April (with a slight upward revision for 2016). However, should growth in the European Union be affected significantly, the adverse effect on China could be material.

- The outlook in other large emerging markets has changed slightly. Consumer and business confidence appears to have bottomed out in Brazil, and the GDP contraction in the first quarter was milder than anticipated. Consequently, the 2016 recession is now projected to be slightly less severe, with a return to positive growth in 2017. Political and policy uncertainties remain, however, and cloud the outlook. Higher oil prices are providing some relief to the Russian economy, where the decline in GDP this year is now projected to be milder, but prospects of a strong recovery are subdued given long-standing structural bottlenecks and the impact of sanctions on productivity and investment. In India, economic activity remains buoyant, but the growth forecast for 2016-17 was trimmed slightly, reflecting a more sluggish investment recovery.

- The outlook for other emerging market and developing economies remains diverse. Growth projections were revised down substantially in sub-Saharan Africa, reflecting challenging macroeconomic conditions in its largest economies, which are adjusting to lower commodity revenues. In Nigeria, economic activity is now projected to contract in 2016, as the economy adjusts to foreign currency shortages as a result of lower oil receipts, low power generation, and weak investor confidence. These revisions for the largest low-income country are the main reason for the downgrade in growth prospects for the low-income developing countries group.2 In South Africa, GDP is projected to remain flat in 2016, with only a modest recovery next year. In the Middle East, oil exporters are benefiting from the recent modest recovery in oil prices while continuing fiscal consolidation in response to structurally lower oil revenues, but many countries in the region are still plagued by strife and conflict.

Risks to the Outlook

As noted earlier, with Brexit still very much unfolding, the extent of economic and political uncertainty has risen, and the likelihood of outcomes more negative than the one in the baseline has increased. Box 1 sketches the potential ramifications on the global outlook of two alternative scenarios, which envisage a more acute tightening of global financial conditions and larger confidence effects as a result of Brexit than those assumed in the WEO baseline.

Other risks have become more salient. The Brexit shock occurs amid unresolved legacy issues in the European banking system, in particular in Italian and Portuguese banks, as identified in the Global Financial Stability Report. Protracted financial market turbulence and rising global risk aversion could have severe macroeconomic repercussions, including through the intensification of bank distress, particularly in vulnerable economies. Continued reliance on credit as a growth driver is heightening the risk of an eventual disruptive adjustment in China. Many commodity exporters still confront the need for sizable fiscal adjustments, and emerging market economies more broadly need to be alert to financial stability risks. Risks of noneconomic origin also remain salient. Political divisions within advanced economies may hamper efforts to tackle long-standing structural challenges and the refugee problem; and a shift toward protectionist policies is a distinct threat. Geopolitical tensions, domestic armed strife, and terrorism are also taking a heavy toll on the outlook in several economies, especially in the Middle East, with further cross-border ramifications. Other ongoing concerns include climate-related factors– e.g., the drought in East and Southern Africa—and diseases such as the Zika virus afflicting the Latin America and Caribbean region.

Policy implications

Central banks were prepared for possible effects from the referendum and responded quickly to its outcome. In particular, major central banks stood ready to provide domestic currency liquidity and also to alleviate shortages of foreign exchange liquidity through swap lines. Their preparedness has supported confidence in market resilience. Going forward, policy makers in the United Kingdom and the European Union have a key role to play in helping to reduce uncertainty. Of primary importance is a smooth and predictable transition to a new set of post-exit trading and financial relationships that as much as possible preserves gains from trade between the United Kingdom and the European Union.

Most advanced economies continue to confront significant economic slack and a weak inflation outlook, with further downside risks in this more uncertain environment. To address these challenges, a combination of near-term demand support and structural reforms to reinvigorate medium term growth remains essential under the baseline—all the more so given the increasingly fragile and uncertain environment. The effectiveness of policy support would be enhanced by exploiting synergies among a range of policy tools, without leaving the entire stabilization burden on the shoulders of central banks. And greater reliance on measures to support domestic demand, especially in creditor countries with policy space, would help reduce global imbalances while contributing to stronger world growth. As discussed in Chapter 3 of the April 2016 WEO the effectiveness of structural reforms can be enhanced by careful sequencing and appropriate macroeconomic support, including from more growth-friendly fiscal policy. Remaining financial sector vulnerabilities, especially those in Europe’s banking sector—legacies of the global financial crisis and its aftermath—must be tackled quickly and decisively to ensure a financial system resilient to the protracted periods of uncertainty and turbulence that may lie ahead.

Policy challenges are more diverse across emerging market and developing economies, but in most cases they also include a need to bolster medium-term growth prospects through structural reforms. The scope for short-run demand support varies across countries, but may be limited in periods of heightened global risk aversion. Policymakers should strengthen defenses against protracted periods of global financial turbulence and tighter external financial conditions.

Priorities include reining in excess credit growth where needed, supporting healthy bank balance sheets, containing maturity and currency mismatches, and maintaining orderly market conditions.

And policymakers need to stand ready to act more aggressively and cooperatively should the impact of financial market turbulence and higher uncertainty threaten to materially weaken the global outlook.

Box 1. Alternative Scenarios for the Global Economy in the Aftermath of Brexit

The vote in the United Kingdom in favor of leaving the European Union adds significant uncertainty to an already fragile global recovery. The vote has caused significant political change in the United Kingdom, generated uncertainty about the nature of its future economic relations with the European Union, and could heighten political risks in the European Union itself. This erosion of confidence was reflected in a large initial selloff in global financial markets, which has since partly reversed. But continuing uncertainty is likely to weigh on consumption and especially investment.

The impact and persistence of that uncertainty are hard to quantify at this stage. The financial market reaction so far has been generally orderly and contained. However, global confidence effects and tighter financial conditions—amid the prolonged negotiations that are likely to precede a new relationship between the United Kingdom and the European Union—could affect global growth negatively beyond what is envisaged in the baseline scenario.

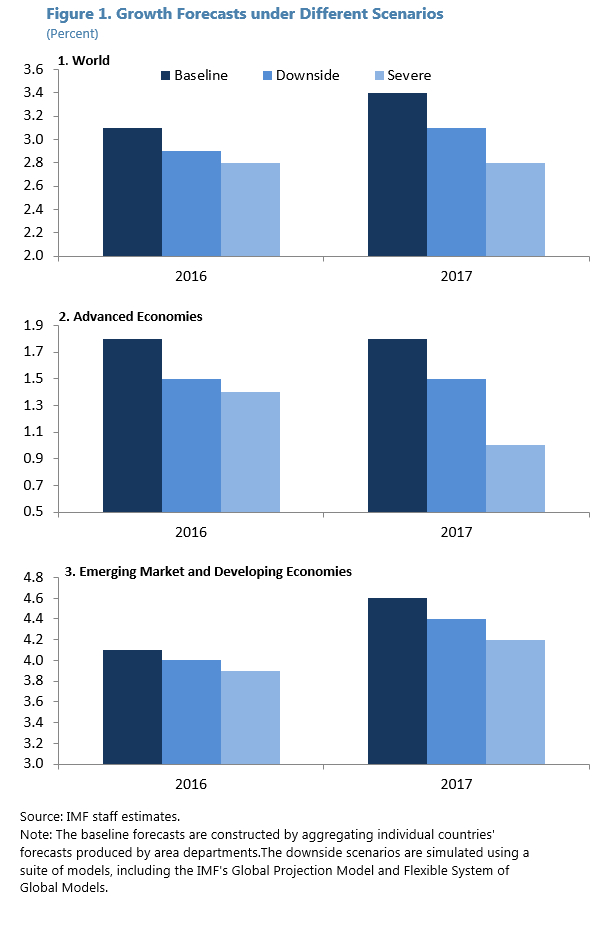

In comparison to this report’s baseline forecast, this box presents two alternative scenarios for the global economy, labeled “downside” and “severe.” The scenarios are based on a structural model-based approach and judgment about the possible negative repercussions of Brexit on the global economy, including through a more severe financial market reaction than what has been observed so far (Figure 1).3 Both alternative scenarios have become less likely over time as financial markets have continued to stabilize following the Brexit referendum.

Under the downside scenario, it is assumed that financial conditions are tighter and that business and consumer confidence are lower than in the baseline, both in the United Kingdom and the rest of the world until the first half of 2017, thus negatively affecting consumption and investment relative to the WEO baseline. Furthermore, a portion of U.K. financial services is assumed to gradually relocate to the euro area, taking a further toll on U.K. activity. The direct spillover effects from the contraction of U.K. imports are negligible for global trade. However, spillover effects to the rest of the European Union and other countries emanating from an increase in global risk aversion and tighter financial conditions play a more dominant role. Accordingly, the impact on global growth would be a further slowdown for the remainder of 2016 and 2017 relative to the baseline scenario.

The less probable severe scenario envisages an intensification of financial stress, especially in advanced Europe, leading to a sharper tightening of financial conditions and larger confidence effects, in line with the “adverse scenario” outlined in the IMF’s 2016 United Kingdom Staff Report. Negotiations between the United Kingdom and the European Union do not proceed smoothly and trade arrangements eventually revert to WTO rules. A larger portion of U.K. financial services is assumed to relocate to the euro area. This would reduce consumption and investment more markedly relative to the baseline and lead to a recession in the United Kingdom. Trade and financial spillovers are more significant than under the moderate scenario. As a result, the global economy would experience a more significant slowdown for the remainder of 2016 and 2017 that would be more pronounced in advanced economies.

1 Specifically, the oil price assumptions used for the current WEO Update are about $10 higher for 2016 and 2017 than those used for the April 2016 WEO.

2 Growth projections for most countries in this group, as well as for several small advanced and emerging market economies, are unchanged relative to April and will be updated in October 2016.

3 WEO forecasts are constructed by aggregating individual country’s forecasts produced by area departments. The simulations in this box were undertaken using a suite of models, including the Fund’s Global Projection Model (see IMF Working Paper No. 13/256, 2013) and the Fund’s Flexible System of Global Models (see IMF Working Paper No. 15/64, 2015).

Table 1. Overview of the World Economic Outlook Projections(Percent change unless noted otherwise) | |||||||||||

| Year over Year | |||||||||||

| Difference from April 2016 WEO Projections 1/ |

Q4 over Q4 | ||||||||||

| Estimates | Projections | Estimates | Projections | ||||||||

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2016 | 2017 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |||

|

World Output 2/ |

3.4 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.4 | -0.1 | -0.1 | 3.0 | 3.2 | 3.5 | ||

|

Advanced Economies |

1.9 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 1.8 | -0.1 | -0.2 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.9 | ||

|

United States |

2.4 | 2.4 | 2.2 | 2.5 | -0.2 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 2.3 | ||

|

Euro Area |

0.9 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 0.1 | -0.2 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 1.5 | ||

|

Germany |

1.6 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 0.1 | -0.4 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.3 | ||

|

France |

0.6 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 0.4 | -0.1 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.4 | ||

|

Italy |

-0.3 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.0 | -0.1 | -0.1 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

|

Spain |

1.4 | 3.2 | 2.6 | 2.1 | 0.0 | -0.2 | 3.5 | 1.8 | 2.5 | ||

|

Japan |

0.0 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.1 | -0.2 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.2 | ||

|

United Kingdom |

3.1 | 2.2 | 1.7 | 1.3 | -0.2 | -0.9 | 1.8 | 1.2 | 1.5 | ||

|

Canada |

2.5 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 2.1 | -0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 1.8 | 2.2 | ||

|

Other Advanced Economies 3/ |

2.8 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.3 | -0.1 | -0.1 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 2.6 | ||

|

Emerging Market and Developing Economies |

4.6 | 4.0 | 4.1 | 4.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.1 | 4.4 | 4.9 | ||

|

Commonwealth of Independent States |

1.0 | -2.8 | -0.6 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 0.2 | -3.4 | -0.3 | 1.8 | ||

|

Russia |

0.7 | -3.7 | -1.2 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 0.2 | -4.0 | -0.3 | 1.8 | ||

|

Excluding Russia |

1.9 | -0.6 | 1.0 | 2.5 | 0.1 | 0.2 | . . . | . . . | . . . | ||

|

Emerging and Developing Asia |

6.8 | 6.6 | 6.4 | 6.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.8 | 6.3 | 6.3 | ||

|

China |

7.3 | 6.9 | 6.6 | 6.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 6.8 | 6.5 | 6.1 | ||

|

India 4/ |

7.2 | 7.6 | 7.4 | 7.4 | -0.1 | -0.1 | 8.1 | 7.4 | 7.4 | ||

|

ASEAN-5 5/ |

4.6 | 4.8 | 4.8 | 5.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.8 | 4.5 | 5.3 | ||

|

Emerging and Developing Europe |

2.8 | 3.6 | 3.5 | 3.2 | 0.0 | -0.1 | 4.1 | 3.3 | 3.0 | ||

|

Latin America and the Caribbean |

1.3 | 0.0 | -0.4 | 1.6 | 0.1 | 0.1 | -1.4 | 0.0 | 2.1 | ||

|

Brazil |

0.1 | -3.8 | -3.3 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | -5.9 | -1.2 | 1.1 | ||

|

Mexico |

2.2 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.8 | ||

|

Middle East, North Africa, Afghanistan, and Pakistan |

2.7 | 2.3 | 3.4 | 3.3 | 0.3 | -0.2 | . . . | . . . | . . . | ||

|

Saudi Arabia |

3.6 | 3.5 | 1.2 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 1.8 | 1.0 | 2.4 | ||

|

Sub-Saharan Africa |

5.1 | 3.3 | 1.6 | 3.3 | -1.4 | -0.7 | . . . | . . . | . . . | ||

|

Nigeria |

6.3 | 2.7 | -1.8 | 1.1 | -4.1 | -2.4 | . . . | . . . | . . . | ||

|

South Africa |

1.6 | 1.3 | 0.1 | 1.0 | -0.5 | -0.2 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 1.1 | ||

|

Memorandum |

|||||||||||

|

Low-Income Developing Countries |

6.0 | 4.5 | 3.8 | 5.1 | -0.9 | -0.4 | . . . | . . . | . . . | ||

|

World Growth Based on Market Exchange Rates |

2.7 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 0.0 | -0.1 | 2.3 | 2.6 | 2.8 | ||

|

World Trade Volume (goods and services)6/ |

3.7 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 3.9 | -0.4 | 0.1 | . . . | . . . | . . . | ||

|

Advanced Economies |

3.6 | 3.8 | 2.6 | 3.9 | -0.4 | 0.1 | . . . | . . . | . . . | ||

|

Emerging Market and Developing Economies |

3.9 | 0.6 | 2.9 | 3.9 | -0.5 | 0.1 | . . . | . . . | . . . | ||

|

Commodity Prices (U.S. dollars) |

|||||||||||

|

Oil 7/ |

-7.5 | -47.2 | -15.5 | 16.4 | 16.1 | -1.5 | -43.4 | 13.7 | 5.2 | ||

|

Nonfuel (average based on world commodity export weights) |

-4.0 | -17.5 | -3.8 | -0.6 | 5.6 | 0.1 | -19.1 | 5.0 | -2.7 | ||

|

Consumer Prices |

|||||||||||

|

Advanced Economies |

1.4 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 1.6 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 1.7 | ||

|

Emerging Market and Developing Economies 8/ |

4.7 | 4.7 | 4.6 | 4.4 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 4.6 | 4.3 | 4.0 | ||

|

London Interbank Offered Rate (percent) |

|||||||||||

|

On U.S. Dollar Deposits (six month) |

0.3 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 0.0 | -0.3 | . . . | . . . | . . . | ||

|

On Euro Deposits (three month) |

0.2 | 0.0 | -0.3 | -0.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | . . . | . . . | . . . | ||

|

On Japanese Yen Deposits (six month) |

0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | -0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | . . . | . . . | . . . | ||

|

Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook Update, July 2016 Note: Real effective exchange rates are assumed to remain constant at the levels prevailing during June 24–June 28, 2016. Economies are listed on the basis of economic size. The aggregated quarterly data are seasonally adjusted. 1/ Difference based on rounded figures for both the current and April 2016 WEO forecasts. 2/ Countries included in the calculation of quarterly estimates and projections account for approximately 90 percent of world GDP at purchasing power parities. 3/ Excludes the G7 (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, United Kingdom, United States) and euro area countries. 4/ For India, data and forecasts are presented on a fiscal year basis and GDP from 2011 onward is based on GDP at market prices with FY2011/12 as a base year. 5/ Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam. 6/ Simple average of growth rates for export and import volumes (goods and services). 7/ Simple average of prices of U.K. Brent, Dubai Fateh, and West Texas Intermediate crude oil. The average price of oil in U.S. dollars a barrel was $50.79 in 2015; the assumed price based on futures markets (as of June 28, 2016) is $42.9 in 2016 and $50.0 in 2017. 8/Excludes Argentina and Venezuela | |||||||||||