80 Years of Bretton Woods and the Challenges Ahead

March 4, 2024

Good afternoon. It is an honor to speak to so many great colleagues and friends. Thank you, Governor Holzmann, for convening us, and congratulations to Austria on seventy-five years of IMF membership.

In my remarks today, I would like to comment on the themes of our panel, including the changing role of the Bretton Woods institutions over the past 80 years, present-day challenges to multilateralism, and conclude with a brief discussion of Special Drawing Rights—the IMF’s global reserve asset—in light of lessons learned from the August 2021 $650 billion general allocation.

For 80 years, our job has been to promote international monetary cooperation. The IMF is a learning institution. We continue to adapt to shared global challenges, within our mandate and in service to our membership. As we navigate new challenges and disruptive transitions, we remain committed to adapt and evolve to best support the prosperity of our members.

One Mandate with New Roles for the IMF

Per our Articles of Agreement, the mandate of the IMF is to promote monetary cooperation and the stability of the international monetary system, facilitate international trade to support sustainable economic growth and employment, and provide temporary support to our members to address balance of payments difficulties.

The central principle of our mandate is assisting members to overcome balance of payments problems without resorting to measures that threaten national or international prosperity. Indeed, new global trends can manifest themselves—to lesser or greater degrees—in the balance of payments of individual countries. The interpretation of our mandate has thus evolved over the past 80 years with shifts in the global economy. The world looks very different today than it did in 1944. So, while our mandate has not changed since the 1944 Bretton Woods Conference, we continue to adapt with the times.

For example, on surveillance, we strongly emphasized macro-financial linkages in the wake of the global financial crisis. More recently, the IMF has had to become more concerned with domestic policies and their spillovers.

On lending, the IMF has refined its lending toolkit. After the collapse in global commodity prices in the early 1980s, many low-income developing countries, particularly in Africa, faced difficulties. In response, we introduced the Enhanced Structural Adjustment Facility in 1987. It was specifically designed to provide low-interest loans to poor countries to address balance of payments problems. More recently, we introduced precautionary arrangements, recognizing the different causes of balance of payments problems for different country groups. We also integrated more structural policy issues into IMF programs.

Importantly, our activities are guided by macro-criticality. By this we mean whether a policy or issue significantly affects a country’s present or prospective balance of payments or domestic stability. Fiscal, monetary, and financial policies would always be considered macro-critical. Depending on country specific characteristics, macro-criticality can extend to a wide range of issues such as climate change, inequality, digital developments, and demographic shifts. We are adapting our policy advice, lending programs, and technical assistance to best support our members.

Our analytical work on climate focuses on modalities to incentivize decarbonization, which could be implemented through a combination of carbon pricing and non-pricing instruments, including taxes, emissions trading schemes, subsidies, or regulations, with a carbon price floor differentiated by members’ development level possibly accelerating the process. We are also developing tools and models to incorporate the impact of climate change and climate policies (mitigation, adaptation, and transition) into our macro frameworks. Through our support for climate risk analyses and supervision, we aim to develop members’ financial sector resilience to climate risks. In collaboration with partners, we are also helping members strengthen local capital markets and scale up private climate finance.

In a more shock-prone environment with new and evolving global risks, the IMF must be forward-looking and attuned to evolving policy challenges. We need to strive to help our members build resilience against potentially disruptive structural shifts related to climate, demographics, technology, and geopolitics, in coordination with other international institutions. To fulfill our mandate, the IMF needs to remain representative of its global membership and well resourced. It is therefore essential to safeguard our financial strength while further enhancing its surveillance and capacity development efforts.

Promoting Global Cooperation Among Challenges to Multilateralism

The world is going through a series of profound new transformations related to climate change, digitalization and artificial intelligence, and demographic transition. Moreover, after several decades of increasing global economic integration, we are now facing a surge of policy measures that put the world at risk of fragmentation. Still-elevated inflation and slowing growth add to this challenging global economic environment.

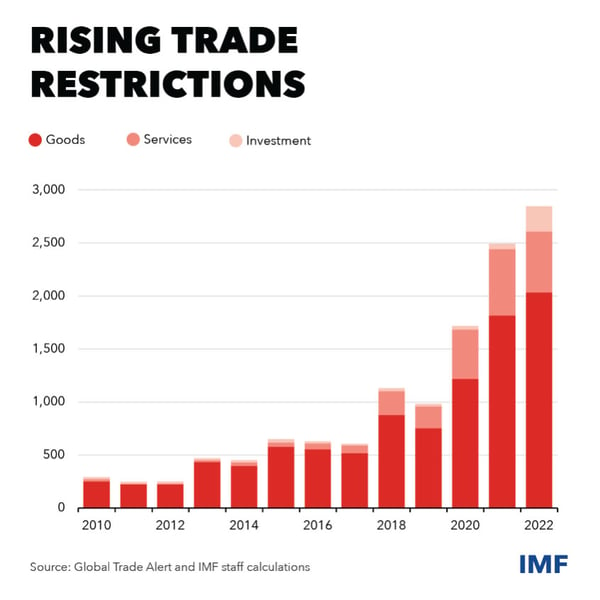

There are signs that global fragmentation is increasing. For example, the number of new trade barriers introduced in 2023 was three times higher than in 2019 (see chart). Industrial policies driven by geopolitical concerns are on the rise, and there is growing evidence that countries are redirecting trade towards politically closer countries. Depending on economies’ ability to adjust, the losses from fragmentation could be high.

After an extended period of low global inflation, 2022 saw the largest global increase in prices for more than 20 years. While headline inflation is dropping steadily, as supply chain disruptions have eased and commodity prices have declined, mean global core inflation is generally projected to decline more gradually. Managing near-term inflation expectations through effective communication and improved monetary policy frameworks will be central to achieving a soft landing. Promoting diversified supply chains and avoiding beggar-thy-neighbor protectionist strategies will also be key to managing future supply shocks.

Meanwhile, effectively responding to emerging global challenges requires stronger international cooperation.

The IMF is working toward maintaining and deepening global cooperation by pursuing targeted progress where common ground exists and maintaining collaboration in areas where inaction would be devastating for its members. The IMF does so through rigorous surveillance and consistent and evenhanded policy advice to its members, including analysis of spillovers from unilateral actions. The IMF also uses its convening power to bring together 190 member countries to discuss issues of common interest and develop common approaches. The IMF must continue to advocate for open, stable, and transparent trade policies to lean against fragmentation, including pragmatic approaches.

One area where we are promoting cooperation and pragmatic multilateralism is in sovereign debt restructuring. Last year, along with India as G20 President and the World Bank as co-chairs, we launched the Global Sovereign Debt Roundtable, which brings together public and private creditors, as well as borrowers, to accelerate restructuring cases, including those under the G20’s Common Framework. Engagement in the Global Sovereign Debt Roundtable has proven useful. All participants have been constructive, and GSDR discussions have helped increase a common understanding on technical issues that were blocking progress in individual restructuring cases, including on the role of MDBs, the perimeter of debt to be restructured, and comparability of treatment, to name a few. While more work needs to be done, our efforts have promoted mutual understanding and are facilitating timely debt restructurings.

Special Drawing Rights

Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) deserve a special mention as an example of how the IMF and its membership have promoted cooperative responses to shared challenges.

SDRs were created in 1969 to supplement IMF member countries’ official reserves. Since then, several general SDR allocations took place to help meet global reserve needs.

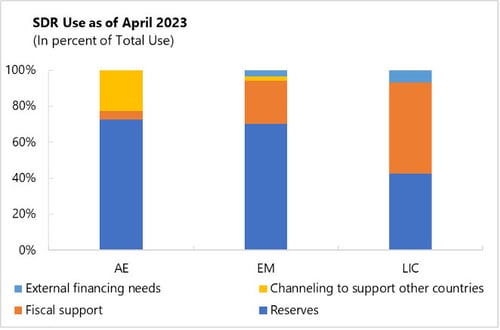

The largest SDR allocation in history took place in August 2021, with a general allocation of SDRs 456 billion (about $650 billion). This allocation injected much-needed reserves and liquidity to member countries during a period of exceptionally high uncertainty, while also helping meet the long-term global demand for reserves. As discussed in our 2023 Ex-Post Report, the allocation was truly a “shot in the arm” for the global economy confronting the pandemic and its implications. Several emerging market and developing economies used their SDRs to improve the composition of financing and repay debt, while others sold foreign exchange to Finance Ministries in exchange for local currency treasury bonds, boosting foreign exchange liquidity without debt issuance (see chart). Overall, the 2023 SDR Allocation Ex-Post Report found that the allocation was beneficial for the global economy.

It is important to stress that while an SDR allocation is a useful mechanism to build confidence, to strengthen global economic and financial resilience, it is not a silver bullet and needs to be utilized only at times of global crises. It is also a very blunt tool as most of the allocation goes to higher income countries, as it is linked to members’ quota shares at the IMF. In October 2021, the G20 pledged to channel US$100 billion (20 percent of their SDR allocation) for the benefit of vulnerable members and have mostly delivered on this pledge through the Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust (PRGT) and Resilience and Sustainability Trust (RST). Such financing is a source of crucial policy and balance of payments support.

Through the PRGT, we provide crucial balance of payments support to deal with external shocks and to support programs that involve debt restructurings. Such financing helps restore macroeconomic stability and strengthen economic institutions, which is critical to unlock needed additional financing from donors and the private sector for growth-enhancing investments. Total pledges for loan resources, as well as deposit and investment agreements that generate resources for PRGT subsidies, stand at almost US$55 billion from 29 contributing countries. Over 95 percent of these resources or about US$53billion have become effective to date.

The RST is the first-ever mechanism for the IMF to provide affordable long-term financing to help countries address structural challenges like climate change and pandemic preparedness. Current pledges stand at almost US$42.2 billion from 21 countries, with about US$40 billion effective.

Conclusion

In sum, the IMF continues to adapt in service to our membership, in response to new global risks related to our mandate. We will continue to deliver significant benefits to our membership as they navigate new shared challenges and disruptive transitions, just as we have for our first 80 years. Thank you.