Global Economic Challenges and Opportunities

September 25, 2017

Good morning. Thank you, Manuel, for your kind introduction. I greatly appreciate the speaking invitation from National Association for Business Economics. And I am very happy to join you today in Cleveland. As you know, I have just come from Washington where Nationals fans are very excited about the World Series. Who knows? They might be meeting the Indians. So, best wishes to both teams.

We are meeting at a moment of serious global concerns: natural disasters, geopolitical tensions, deep political divisions in many countries.

Allow me, then, to bring offer some good news today.

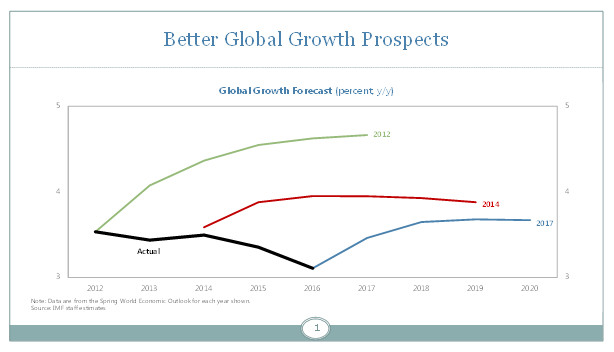

Nearly a decade after the global financial crisis, the global economy is getting better. The most recent IMF forecast, issued in July, projected global growth at 3.5 percent this year and 3.6 percent in 2018, up from 3.2 percent in 2016. The Fund will issue its next World Economic Outlook in a week, and there is every reason to see these trends continuing.

This first chart shows how our forecasts have changed over the past five years. The rebound from the crisis took longer than expected to arrive, but we now are seeing positive momentum.

Here in the United States, our July forecast saw growth accelerating from 1.6 percent last year to 2.1 percent this year and next. By early next year, the United States could be experiencing its second-longest expansion since 1850.

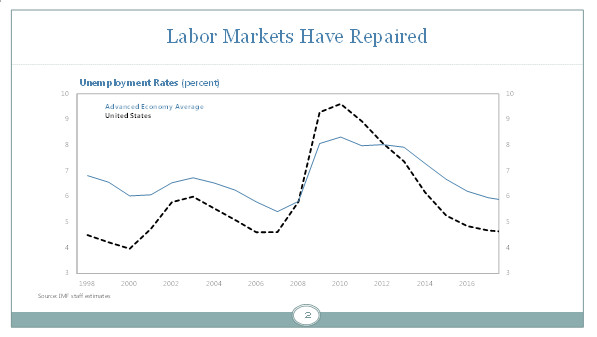

Most importantly, many countries are creating new jobs at a healthy pace. Over the past year in the United States, almost 2.2 million jobs were created. As this second chart shows, the unemployment rate is close to the lows we saw in 2000.

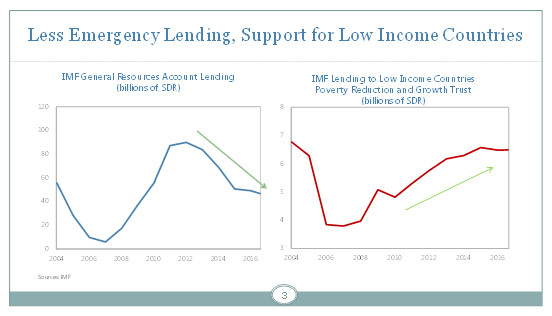

What does this mean for the IMF? As the impact of the global crisis has faded, countries have found their financial footing again.

So, our emergency lending has naturally declined—as the chart on the left side of this next slide demonstrates. This is also a good sign. Our outstanding loans are now one-half of their peak in 2012.

However, at the same time, the world’s poorest countries are seeking higher levels of financial support through our concessional lending facilities. This is reflected in the chart. A major reason for the increase in borrowing is the impact of the sharp fall in commodities prices experienced after 2015.

So clearly, the picture is not all positive. But, all in all, significant healing has taken place over the past several years.

Now there is more to be done. From a historical perspective, global growth of 3 and one-half percent is weak. Achieving stronger growth will require the right combination of policies, especially to reinforce labor and capital markets. Many industries need to operate more efficiently, and competitiveness needs to be strengthened. This will require a range of reforms.

So, I would like to focus my remarks on four broad topics that I believe deserve attention:

- the slowdown in productivity growth;

- income polarization;

- low inflation and low levels of wage growth;

- and the continuing need for global cooperation.

1: The productivity slowdown

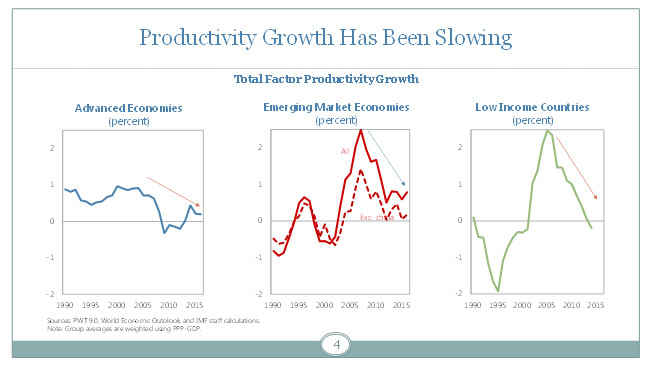

Let’s begin with productivity. After the global financial crisis, it became clear that we were witnessing a slowdown in productivity growth across a range of countries. This was unusual both in terms of the extent of the decline, and because it occurred across advanced, emerging market, and low-income countries. This is shown in the next slide.

What makes this slowdown more puzzling is that it comes at a time of significant innovation and technological change.

As I speak, I see many of you are on your tablets and smartphones. This is an area of innovation that perhaps has received more attention than any other. Some may argue that it increases productivity; some may argue the opposite. Certainly, it has made our lives more interesting. Without a doubt, the globally integrated production system that has grown up to supply our gadgets is quite remarkable.

It is not only the IT sector that has advanced. Think of oil and gas. Technological progress in this industry has been remarkable. The cost of producing energy has fallen sharply. This has transformed the energy matrix in several countries (including here in the United States). And yet, this industry also is facing extraordinary competition from the rapid growth of renewable energy resources.

Think also of the rapid transformation of the retail industry, where stores and shopping malls are being rapidly replaced by websites.

Whatever the industry, innovation has reshaped labor and product markets.

However, this disruptive change has taken place without an apparent increase in productivity. This is very different from previous periods of rapid innovation and technological change.

There are competing explanations for this tension, and research has yet to identify the most empirically relevant factors. There are various candidates:

- Some argue there is a measurement error; that the data does not capture large parts of the new economy. There is some evidence that this may explain that the level of GDP and productivity are underestimated. However, the evidence so far does not point to an explanation for the decline in the growth of productivity.

There is also an argument about mismeasurement because of the impact of transfer pricing and other factors associated with globalization.

- Others point to an increasing share of economic activity not included in GDP. This would be non-market activities that were never intended to be part of GDP: household production, the bartering of goods and services, or unpaid services. This goes beyond mismeasurement.

- A third explanation could be that much of the innovation we have witnessed is doing little to make the pie bigger through more productive means of production. Rather, that innovation could be intensifying a trend of redistribution of the growth dividends away from labor and toward capital. The bottom line may be little overall improvement in productivity.

One, or all, of these explanations could contribute to the decline in productivity. But there is no consensus on the relative impact.

2: Income polarization .

This brings me to my next topic: the ongoing dynamic in the advanced economies of polarized income distribution. We have seen this trend, to different degrees, in both Europe and in the United States.

This connects back to the productivity issue. The point here is that is has become more difficult to raise living standards in several advanced economies.

But there’s more going on than just the decline in productivity and weak income growth. In inflation-adjusted terms, more than one half of U.S. households have lower incomes today than they did in 2000. There are also distributional forces at work.

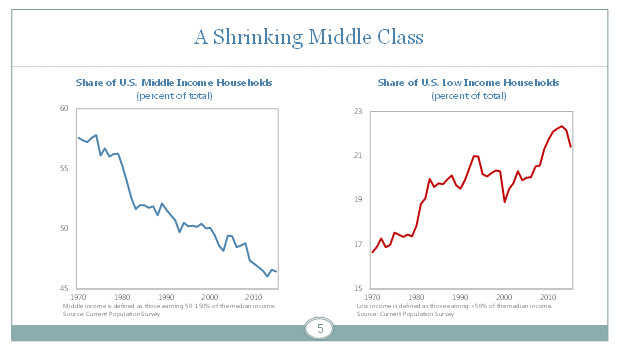

In this slide, the left-hand chart shows the declining share of households in the U.S. that earn between one-half and twice the median income—this is the center of the income distribution that we may think as the “middle class”. This group has experienced a persistent and pronounced decline.

Around two-thirds of those are moving out of this “middle” have fallen into the “bottom” of the income distribution—the group that earns less than one half of the median wage. This is shown in the right-hand chart, where the share of the U.S. population earning less than 50% of median income is clearly on the rise.

It is no wonder that some economists speak of a hollowing out of the middle class in the advanced economies.

Recent IMF research on the United States suggests that a significant component of income polarization can be linked to technological change. And it is specifically related to the automation and off-shoring of semi-skilled tasks. In many cases, these were the jobs that provided middle-class incomes.

We have also found that the growing concentration of income and wealth has reduced aggregate consumption—by about 3 and a half percent over the past 15 years. This represents an important headwind to aggregate demand.

I know all of us are aware of the social and political ramifications that have accompanied these shifts in the level and distribution of household income. We are seeing increased dissatisfaction among electorates and a sharp swing of sentiment against globalization.

That said, there are policies that can help address the problem of income inequality. These include:

- well-targeted social assistance programs;

- improved access to education and retraining;

- the expansion of the Earned Income Tax Credit, combined with a higher minimum wage;

- support for working parents to meet child-care costs; and

- paid family leave.

Our purpose in making these recommendations is to address the severe social impact of income polarization. We all need to provide the opportunities that enable people to take advantage of innovation and entrepreneurship.

3: Low inflation and low levels of wage growth.

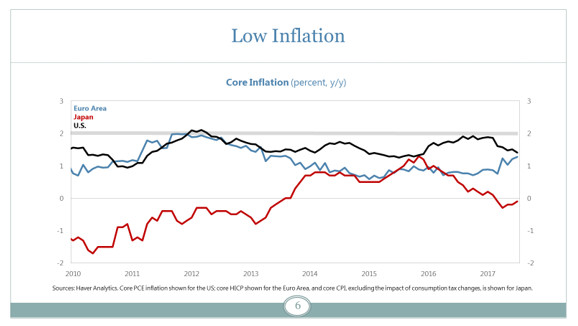

The third topic I want to highlight is the generally low level of global inflation and wage growth, especially in the advanced economies. As the next slide shows, core inflation in Europe is somewhat below the ECB’s goal of below-but-close-to 2 percent. In Japan, headline and core inflation are close to zero. And here in the U.S., despite earlier progress in getting inflation to rise toward the Fed’s 2 percent goal, we have seen a reversal over the past several months. Core and headline inflation are both now at 1.4 percent.

Linked to this subdued inflation is the relatively low level of nominal wage growth.

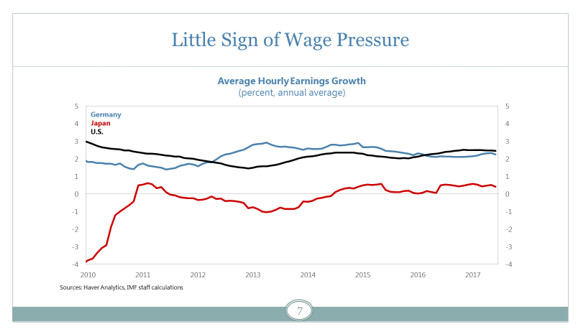

In our assessment, the United States, Germany, and Japan are now close to full employment. But even as labor markets have strengthened, there does not seem to be a strong push for nominal wages to rise – as can be seen from this chart. There certainly is little evidence of wage pressure.

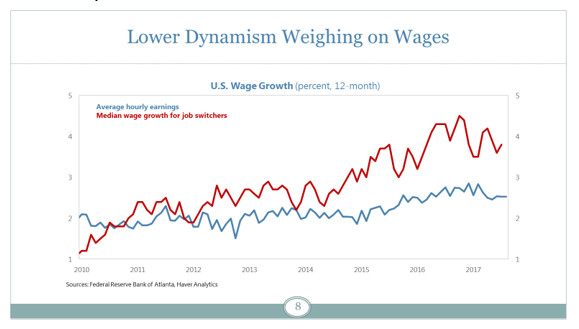

Important structural forces are contributing to this low wage growth. Again, one is the decline in productivity growth. We also are witnessing reduced labor market dynamism. One example of declining labor dynamism is that job-to-job moves have declined by about 40 percent since the late 1980s.

This is important because the largest wage increases go to those who switch jobs. In this chart, we see the gap between the average economy-wide wage increase and the pace of wage increases for those individuals who are changing jobs. Less dynamism means less job switching, which arithmetically translates into lower average wage growth.

There may be other secular forces at play. One is demographic change, as seen in the aging of many advanced economies. Another is the increasing consolidation of companies into ever-larger combinations, which strengthens employers’ bargaining power and compresses wages.

Differentiating the various drivers is a tough task. But, regardless of the cause, we know that stronger nominal wage growth will be needed to put inflation back on track toward central banks’ targets.

4: Global Cooperation

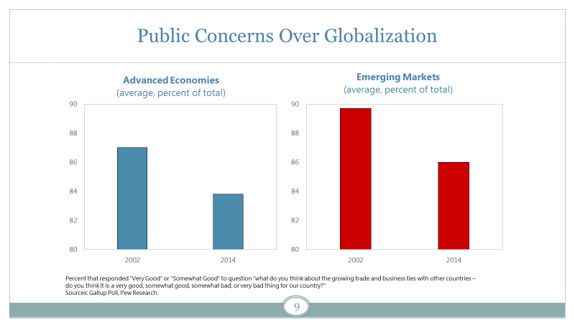

Finally, as a representative of the IMF, the last topic that I would like to raise will not come as no surprise. I have already touched on it. There is a concern that a more integrated and globalized world economy is no longer generating the jobs and higher living standards that once were promised. We are seeing this across the advanced and emerging market economies, as this final slide shows.

But the reaction to these concerns should not be to try to slow the pace of technological change or global integration. We cannot overlook the important, positive changes that these forces have produced. Witness, for example, the impressive reduction of poverty across the developing world over the past generation.

We must avoid policies that create unexpected, negative spillovers; that increase tensions between countries; or that erode the broad support for economic integration that still exists in the international community. Interrupting the free flow of goods and investments is not a solution. It will only make matters worse by disrupting trade relations and supply chains.

We should pursue a more positive course. This means continuing to maximize the benefits of globalization and technology, but also making the international system work better for all its citizens. It means promoting a multilateral system that adjusts to an increasingly connected global economy, ensuring a level-playing field that avoids protectionist measures and distortive policies, and by mitigating the impact of global transitions as much as possible.

In conclusion, the process of international economic integration will continue to move forward. This is inevitable. But the negative side effects must be acknowledged—and addressed. Part of this task falls to individual countries. But the international community also has a role to play by working together to deal with the cross-border issues. By strengthening the multilateral system, we can safeguard the global economy and ensure strong, stable, and inclusive growth.

Thank you very much for allowing me to speak this morning. I would be very happy to take your questions.

IMF Communications Department

MEDIA RELATIONS

PRESS OFFICER:

Phone: +1 202 623-7100Email: MEDIA@IMF.org