Typical street scene in Santa Ana, El Salvador. (Photo: iStock)

IMF Survey : Top Researchers Debate Unconventional Monetary Policies

November 20, 2015

- IMF conference examines lessons from unconventional monetary policies

- Quantitative easing worked but had no striking effects on the real economy

- Were the “currency wars” ever fought?

Although many countries have adopted unconventional monetary policies since the global financial crisis, the effects of those policies continue to be a matter of debate—all the more so as some central banks, having exhausted their conventional ammunition and with little support from fiscal policy, seem ready to push unconventional measures even further.

The conference concluded with a lively exchange among policy experts: (1-r): Lael Brainard, Paul Krugman, Adam Posen, Claudio Borio, and Maurice Obstfeld (photo: IMF)

Annual Research Conference

The Sixteenth Jacques Polak Annual Research Conference—hosted by the IMF at its Washington, D.C., headquarters on November 5 and 6—gathered some of the best researchers in the field to discuss the lessons and the future of unconventional monetary policies.

Unconventional monetary policies work, but . . .

Much of the recent debate has focused on whether unconventional monetary policies have had the expected effects on asset prices and the real economy. Several conference participants tackled these aspects.

Focusing on asset prices, the Federal Reserve Board’s John Rogers explored the relationship between unconventional monetary policies and risk premiums. He argued that U.S. monetary policy easing significantly lowersterm premiums on domestic and foreign bonds (that is, the extra yield on longer maturities) and foreign exchange risk premiums (that is, the compensation for risks associated with instruments denominated in foreign currency), indicating the relevance of the portfolio balance channel.

Dietrich Domanski, from the Bank for International Settlements,examined how portfolio adjustments by long-term investors (insurers and pension funds) to contain mismatches in the duration of assets and liabilities may have amplified the effects of unconventional monetary policies.

Other presenters discussed how to assess a country’s monetary policy stance and its impact on the real economy when the policy interest rate is lowered to zero, that is, when it hits the zero lower bound. Merrill Lynch’s Dora Xia discussed how to calculate a shadow interest rate summarizing such a monetary stance (a theoretical measure of the effective nominal interest rate that can actually be negative). Using her definition of the shadow rate, she showed that unconventional monetary policies have been successful in loosening monetary policy and stimulating the real economy in the United States.

Eric Engen and David Reifschneider from the Federal Reserve Board explored unconventional monetary policies’ effects on private perceptions about how monetary policy responds to changes in inflation and output. Feeding these perceptions intothe Federal Reserve model for the United States, they find a non-negligible effect on unemployment but argue that the slowadjustment in policy expectations and persistent beliefs that the pace of recovery would be faster than it was have limited the impact of actual monetary policy on real activity and inflation.

Tim Eisert, from Erasmus University Rotterdam, argued that the asset purchase program of the European Central Bank had significantly improved the health of banks in euro area economies under financial stress, by raising the value of their holdings of sovereign debt. Healthier bank balance sheets had resulted in increased loans to the corporate sector, which led to a buildup of cash reserves but no visible improvement in employment or investment.

Overall, these presentations suggested that unconventional monetary policies had a visible impact on asset prices and some effects on the real economy, although of limited magnitude.

Is it time to lift off?

The discussion also shed light on how to lift off from thezero lower bound when the strength of a country’s economy is highly uncertain. The Federal Reserve Board’s David Lopez-Salido argued that, when available information is incomplete, a country’s optimal policy rate may remain at the zero lower bound even when positive signals aboutthe equilibrium real rate would otherwise have called for an increase in the policy rate.

Monetary and fiscal policy interactions matter

Three interesting presentations explored the interaction between unconventional monetary policies and fiscal policy.

Pierpaolo Benigno, from Guido Carli Free International University for Social Studies and the Einaudi Institute for Economics and Finance, explored the inner workings of unconventional monetary policies through their impact on central bank capital and the role of treasury support.

Pushing the boundaries of unconventional monetary policies, Adair Turner, from the Institute for New Economic Thinking, argued for using monetary financing of fiscal deficits as a tool to stimulate aggregate nominal demand and discussed how to design rules to prevent its misuse.

Focusing on the threat of future fiscal crises, Ricardo Reis, a professor at Columbia University and the London School of Economics, examined the stabilizing role that quantitative easing could play at the onset of such events, exploring how balance sheet policies can reduce inflation’s sensitivity to fiscal shocks and prevent a credit crunch by shifting sovereign risk away from banks’ balance sheets.

Should the Fed worry about spillovers?

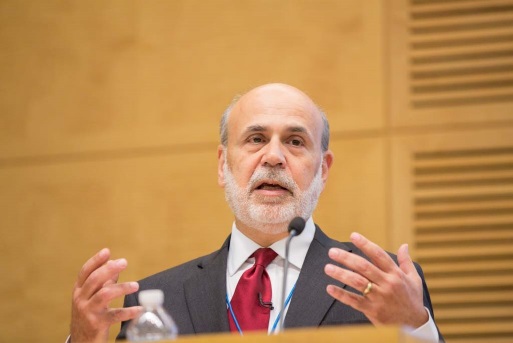

Ben Bernanke: The “currency war” was never fought.

In a highlight of the conference, former Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke, now a Distinguished Fellow at Brookings Institution, delivered the Mundell-Fleming Lecture, focusing on international dimensions of Federal Reserve policies. He downplayed concerns expressed by some emerging market economies about “currency wars,” arguing that monetary easing’s demand-diverting (expenditure-switching) and demand-augmenting (income) effects on emerging-market exports and activity largely offset one another. In his view, “currency war” flags mostly reflect the frustration of open emerging market economies confronted with the trilemma—that is, the difficulty of seeking monetary independence while targeting the exchange rate.

The former Fed chairman also addressed concerns about financial stability spillovers of U.S. monetary policy onto emerging market economies. He argued that a high cross-country correlation of asset returns and other evidence supposedly pointing to a global financial cycle—highlighted in recent research—has not yet built a compelling case for altering U.S. monetary policy on account of possible spillovers. He did support increased international cooperation in financial regulation and continued close consultation on monetary policy.

Other conference participants also focused on international dimensionsofunconventional monetary policies.

Adding to the discussion of possible beggar-thy-neighbor effects (that is, those that improve the fortunes of one country at the expense of others), the Peterson Institute of International Economics’ Joseph Gagnon presented evidence that official purchases of foreign assets and foreign reserve stocks can have sizable effects on a country’s current account, especially when the capital account is closed. However, the domestic-assets purchases typical of quantitative easing involve no such effects.

Feng Zhu from the Bank for International Settlements also analyzed the spillover of unconventional monetary policiesacross major currency blocs and other economies. He argued that monetary policies in the United States and the euro area affect one another, but the magnitudes are asymmetric, as are the effects on third countries.

The Bank of England‘s Tomasz Wieladek focused on the evidence of recent “deglobalization” in cross-border bank lending in the United Kingdom—one of the world largest financial centers—and argued that unconventional policies designed to support domestic credit may unintentionally reduce cross-border lending.

Are unconventional monetary policies suitable for emerging market economies?

Rutgers University Professor Roberto Chang offered a theoretical analysis of various unconventional policies undertaken by emerging market economies in recent years: direct lending to the private sector, liquidity facilities, bank equity purchases, and sterilized foreign exchange operations.

Let’s agree to disagree . . .

The conference concluded with a lively exchange among four distinguished policy experts that highlighted significant unresolved differences in views.

Posen: Let’s stop calling central bank balance sheet expansion and contraction “unconventional.”

Peterson Institute President Adam Posen warned against viewing quantitative-easing-type policies as unconventional. He argued that when movements in the monetary policy rate do not transmit fluidly across asset classes, as evidence suggests, there is a case for using the central bank balance sheet to influence monetary conditions more broadly, even in normal times. He dismissed concerns that quantitative easing will lead to uncontrolled inflation but also stressed that monetary stimulus cannot fully substitute for fiscal policy.

Krugman: Unconventional monetary policy has had none of the predicted negative effects and less than hoped positive effects.

Consistent with the evidence presented throughout the conference, Paul Krugman, Distinguished Professor at the City University of New York and a New York Times columnist, assessed the results of unconventional monetary policies and contended that such policies had not been a game changer, as initially hoped. At the same time, he argued strongly against the view that highly accommodative monetary policy induces financial instability.

Borio: Critical not to overburden monetary policy to avoid being stuck in low growth.

The Bank for International Settlements’ Claudio Borio challenged this benign view on unconventional monetary policies and financial stability. He maintained that reliance on such policies reflects, in part, an asymmetric conduct of monetary policy over the financial cycle, as monetary policy fails to contain financial excesses but responds aggressively and, above all, persistently when the costs of such imbalances materialize. The weak effects of unconventional monetary policies are no surprise in his view, as impaired balance sheets often prevent monetary easing from gaining traction in the aftermath of financial crises. Borio also warned about the risk of falling into a debt trap—with high debt constraining the willingness to raise interest rates toward normal levels. He concluded by stressing the limits to monetary policy and the need to place emphasis on balance sheet repair with fiscal support as well as on structural policies to boost sustainable output growth.

Brainard: U.S. economic and financial conditions sensitive to spillovers from emerging economies.

Lael Brainard, one of the governors of the Federal Reserve, took a different view of the results of unconventional monetary policies, contending that preliminary evidence suggests these policies are effective in overcoming the policy constraints imposed by the zero lower bound. She also challenged the view that unconventional monetary actions have fundamentally distinctive spillover effects on the rest of the world, as they work through the same channels and in similar magnitudes as conventional policies. In her view, announcements of U.S. unconventional monetary policy measures elicited strong negative political reactions because of the discontinuity of discrete policy changes around the zero lower bound and the greater uncertainty that those announcements generated regarding the Federal Reserve policy reaction function.

What now?

After two intense days of lively discussions, we learned a great deal about unconventional monetary and exchange rate policies.

Perhaps a consensus is emerging on how much (conventional and unconventional) monetary policy can achieve. Extraordinary measures prevented a greater economic recession, and arguably a depression, in 2008-09, but—paraphrasing Adam Posen— these “over-the-counter remedies” needed support from the stronger “prescription medicines” of fiscal policy and balance-sheet repair. Countries that have recently gone to the pharmacy for the first time would do well to keep this analogy in mind.

As for other aspects of unconventional monetary policies, such as financial stability implications or spillovers to other countries, it seems that the jury is still out. That means there is still much work to be done, here at the Fund and elsewhere, to fully understand the policy toolkit at our disposal.