Typical street scene in Santa Ana, El Salvador. (Photo: iStock)

IMF Survey : IMF Conference Debates How to Manage Food Price Volatility

March 19, 2014

- Conference examines how best to respond to food price spikes, volatility

- Monetary, fiscal policies can be effective at offsetting food price shocks

- Accessibility of food— not just boosting supply—should be policy priority

With the right combination of economic policies, governments can shield the poor from the effects of food price shocks, participants told an international conference on food price volatility.

Food prices have been high and volatile in the last decade, hurting the poor and food importing countries (photo: Michael Blackburn/iStockphoto)

MANAGING FOOD PRICE VOLATILITY

Academics, policymakers, and representatives of international organizations gathered in Rabat, Morocco, in late February to discuss the causes and socioeconomic challenges of wide fluctuations in food prices.

Food prices have been persistently high and volatile in the last decade, which has widespread welfare implications, disproportionately affecting poor households and food-importing countries.

The two-day event—jointly organized by the IMF, the OCP Policy Center, and New York University’s Center for Technology and Economic Development—focused on appropriate policy responses to spikes in food prices as well as the broader challenge of food security.

Access to food is key

Agricultural production makes up only 3 percent of the global economy, but the sector employs 1.3 billion people, observed Axel Bertuch-Samuels (IMF Special Representative to the United Nations). But while food production is a prominent concern in the face of rising global population, issues of food security go beyond the agricultural sector, participants noted.

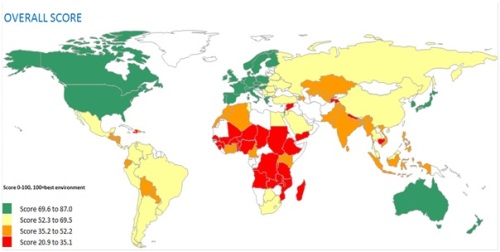

Jomo Kwame Sundaram (Food and Agriculture Organization) suggested that the real issue of food security is not the availability of food, but rather access to food. Government policies are needed to help people procure access to affordable staples, especially the most vulnerable population segments and during periods of food price shocks. These vulnerable populations are largely concentrated in Sub-Saharan Africa and parts of Asia, according to the Global Food Security Index, presented by Leo Abruzzese of the Economist Intelligence Unit.

Results for the 2013 Global Food Security Index

Policymakers from such food-importing African nations as Mauritania, Zimbabwe, Swaziland, and Tunisia shared their strategies for coping with global food price spikes. Their policy responses ranged from cash-for-work programs to compiling strategic grain reserves and encouraging crop rotation. Government interventions deemed successful included subsidized mechanization of agricultural production in Swaziland, inflation targeting in Mauritania, and providing fertilizer and seeds to targeted groups in Zimbabwe.

Food security also involves broader economic development measures, participants observed, such as creating jobs and raising incomes to ensure sustainable access to food.

Both monetary and fiscal instruments needed

The conference considered how policymakers should go about limiting food price inflation. A panel of leading academics and policy experts agreed that monetary policy can be an effective tool in curbing food price inflation, but the fiscal space available to policymakers is an important consideration.

Laurence Ball (Johns Hopkins University) noted that inflation depends on a number of factors, including the degree of slack in the economy, the extent of supply shocks, and the extent to which expectation of inflation are anchored. Prakash Loungani (IMF) presented his study (co-authored by and Susan Wachter of the University of Pennsylvania and John Simon of the Reserve Bank of Australia) confirming that food price shocks contribute to inflation.

Central bank credibility affects the pass-through of food prices to domestic inflation via inflation expectations. Expectations are more anchored in advanced economies than in emerging market countries, but there is also disparity within the emerging markets group depending on whether or not they employ inflation targeting (either implicit or explicit). Those countries that adhere to inflation targets have more anchored expectations than those who do not, the conference heard.

Steven O’Connell (USAID) suggested that central banks should target core—not headline—inflation even in developing economies, where the share of food in consumption basket is relatively high. He showed that the welfare costs of deviating from policy targets are larger in low-income countries than in developed countries, suggesting that central bankers should adhere to their targets more carefully in the emerging economies.

Christophe Gouel (French National Institute for Agricultural Research) presented a paper written with co-authors from the World Bank showing that India’s countercyclical trade policy and government accumulation of wheat stocks have been effective at lessening the effects of food price spikes. However, he noted, their fiscal cost is massive. Increased coordination of the two policies—as well as moving away from buy-and-hold storage policies toward quicker disposal—would help reduce the fiscal burden and maximize welfare, he said.

Ultimately, policies have to be politically legitimate and should aim to reduce unit cost of production and food price volatility rather than lower prices per se, the panel concluded. Direct price controls do not appear to be an effective fiscal policy tool. Instead, panelists argued, investment in agricultural research and infrastructure is imperative.

On the monetary side, inflation targeting can play a role in reducing inflation, which in turn lessens the effects of food price fluctuations, the panel noted. For such countries as India, access to credit can be an important buffer during periods of food price spikes, observed Charan Singh (Indian Institute of Management, Bangalore).

The conference also examined the reasons why food prices fluctuate. Such factors as energy costs—affecting prices via both the supply and demand channels—as well as global commodity prices and stock levels were cited as contributors to domestic food price increases.