Colombia: Peace is Good for Business

September 2018

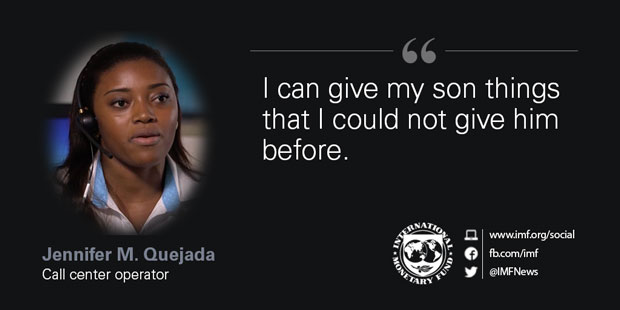

For the first time since the birth of her five-year-old son, Jennifer Mosquera Quejada could afford to throw him a birthday party. The 24-year-old single mother credits her job at a call center in Quibdo, a city of 100,000 deep in the tropical rainforests of western Colombia.

“I can give my son things that I could not give him before,” Quejada says, taking a break from work as a customer service advisor for Telefonica, Colombia’s largest telecommunications company.

Quibdo, a provincial capital, was a place of refuge for people fleeing a guerilla insurgency that lasted five decades, killed 200,000 people and displaced another 6 million.

As part of a peace deal with FARC rebels in 2016, Colombia will build roads, schools, and aqueducts to create jobs and improve the quality of life in previously strife-torn areas. Companies are stepping up investment, and tourism is reviving in a country known for sparkling Caribbean beaches, jungle-glad mountains and abundant wildlife.

Peace agreement

The same year as the peace deal, the government of President Juan Manuel Santos carried out an ambitious overhaul of Colombia’s tax system. The reform, planned with help from the International Monetary Fund, has strengthened government finances and will generate funds for a rural development program estimated to cost $42 billion over 15 years.

“Without this tax reform, it would be impossible to make good on the pledges in the peace agreement,” says Andres Escobar, the deputy finance minister under Santos.

Collaboration between Colombia and the IMF dates to 1999, when the Fund provided a $2.7 billion loan to help the country overcome a severe recession. Among reforms undertaken to put the economy back on track, Colombia adopted a flexible exchange rate, which provided a buffer for economic shocks, and an inflation target to keep prices under control.

“The agreement with the Monetary Fund at that time helped Colombia earn the credibility of the international markets,” says Escobar. “From that point on, the Monetary Fund has been a very important ally.”

The reforms helped Colombia weather the global financial crisis. In 2009, Colombia qualified for a $10.5 billion flexible credit line, an IMF program that makes money available to countries with a track record of strong economic management. The credit line helped reassure international investors, and Colombia didn’t need to draw on it.

Oil prices collapse

Sound economic policies also made it possible to withstand the collapse of oil prices in 2014 that cut export earnings in half and chopped 20 percent off government revenue. The trade deficit widened to a record level in 2015.

The flexible exchange rate acted as a shock absorber, says Mauricio Cardenas, who served as finance minister under Santos. As oil exports fell, the Colombian peso weakened, pushing up the price of imported goods. The result was a decline in imports that helped narrow the deficit.

“Thanks to the flexibility of the exchange rate, we were able to adjust quickly without a recession,” Cardenas says.

But Colombia’s difficulties didn’t end there. Higher prices of imported goods drove up the inflation rate, which peaked above 8 percent in mid-2016. That’s where the central bank’s 3 percent inflation target came into play. The target bolstered public confidence in the central bank, which raised interest rates to bring inflation back down.

The next step was to plug the hole in the government budget left by the drop in oil revenue and, more broadly, to modernize the tax code. The corporate tax rate in Colombia was high by Latin American standards, discouraging investment. Yet tax revenue overall was low, and tax evasion was rampant.

“This reform was an opportunity to make a fundamental change to the Colombian tax system,” Escobar says.

Colombia created a commission to recommend reforms and turned to the IMF for technical advice. In December 2016, the Colombian Congress approved a program that simplified the corporate tax structure and lowered rates. At the same time, it raised the Value Added Tax, a tax on consumption, to 19 percent from 16 percent, bringing more revenue. The authorities strengthened training and staffing at the tax authority, which enacted stiffer penalties for tax evasion.

Urban-rural divide

The tax reform also created incentives for investment in the rural areas formerly controlled by guerillas. That will help address one of the biggest challenges facing the country of 50 million people—the wide disparity in incomes between urban and rural areas.

Roberto Velez, general manager of the National Federation of Coffee Growers, sees enormous potential as new lands are opened for cultivation thanks to the peace deal. Directly or indirectly, coffee cultivation supports 7 million Colombians.

At Promigas, a natural gas distribution company, Chief Executive Officer Antonio Celia is studying a project to install solar panels in remote areas. He sees it as a way of employing former guerillas while providing energy in areas that don’t have natural gas connections.

“A lot of opportunities are going to be generated with the end of the conflict,’’ says Celia, a member of the Business Council for Sustainable Peace, a group that is helping oversee the peace accords. “Peace is good for business, and business is good for peace.”

And at the Telefonica call center in Quibdo, Jennifer Mosquera Quejada is hoping to work in quality control someday. “For me, the idea is to keep working so I can give my son a better future, so he can study at the university.”